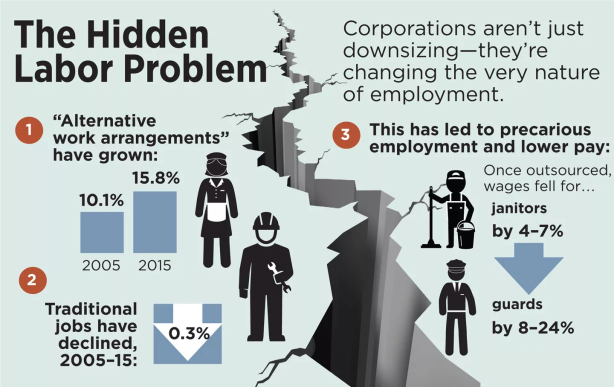

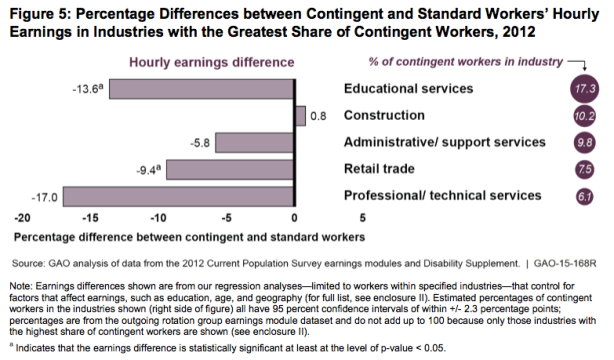

From David Ruccio Donald Trump promised to bring back “good” manufacturing jobs to American workers. So did Hillary Clinton. Both, as I argued back in December, were wrong. What neither candidate was willing to acknowledge is that, while manufacturing output was already on the rebound after the Great Recession, the jobs weren’t going to come back. They were also wrong, as I argued in November, about there being anything necessarily good about factory jobs. But perhaps even more important, as Eduardo Porter reminds us, the focus on manufacturing deflects attention from what is really going on in U.S. workplaces. the vast outsourcing of many tasks — including running the cafeteria, building maintenance and security — to low-margin, low-wage subcontractors within the United States. This reorganization of employment is playing a big role in keeping a lid on wages — and in driving income inequality — across a much broader swath of the economy than globalization can account for. And, according to a recent study by the Government Accountability Office, much of that outsourcing is taking place outside the manufacturing sector. Moreover, the growth of contingent work—for example, 17.3 percent in education services and 6.1 percent in professional/technical services—is accompanied by lower wages, fewer benefits, and more job instability.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Donald Trump promised to bring back “good” manufacturing jobs to American workers. So did Hillary Clinton.

Both, as I argued back in December, were wrong.

What neither candidate was willing to acknowledge is that, while manufacturing output was already on the rebound after the Great Recession, the jobs weren’t going to come back.

They were also wrong, as I argued in November, about there being anything necessarily good about factory jobs.

But perhaps even more important, as Eduardo Porter reminds us, the focus on manufacturing deflects attention from what is really going on in U.S. workplaces.

the vast outsourcing of many tasks — including running the cafeteria, building maintenance and security — to low-margin, low-wage subcontractors within the United States.

This reorganization of employment is playing a big role in keeping a lid on wages — and in driving income inequality — across a much broader swath of the economy than globalization can account for.

And, according to a recent study by the Government Accountability Office, much of that outsourcing is taking place outside the manufacturing sector. Moreover, the growth of contingent work—for example, 17.3 percent in education services and 6.1 percent in professional/technical services—is accompanied by lower wages, fewer benefits, and more job instability.

The problem in the United States is not what workers do or what they produce. It’s how they do what they do.

Employers, not workers, are the ones who decide how labor is performed. And when they can outsource jobs to contractors—and, as a result, avoid unions, workplace regulations, and adequate pay and benefits—they can exercise even more power over their workers, including of course the ones they continue to employ.

That, and not the loss of manufacturing jobs to foreign companies, is the real problem facing the American working-class.