Below, three sets of graphs from three ‘structural’ seconomic tudies which show that the celebrated concept of NAIRU, as defined in these general equilibrium models is little more than a complicated running average of the level of estimated unemployment (though, quite unscientific, economics does not even seem to have an agreed upon algorithm to calculate this average). This a consequence of the assumption of these models that unemployment is a voluntary state of existence. Yesterday, Lars Syll had an interesting post about the nonsense of NAIRU, the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment, as defined in ‘structural macro economic models’. I totally agree but have a little to add. The discussion about NAIRU is not about the interesting relation between unemployment and wages (or even inflation), as proponents state. It is about the relation between unemployment and potential output: when does a government has to stop stimulating demand to prevent runaway inflation? Does this has to happen when unemployment is 3%? Or when unemployment is 4%? Or as the European commission wanted to have it when unemployment is, ahem, 26,6%? The answer is clear: NAIRU won’t give us the answer. Or, as Gechert, Rietzler and Tobler recently stated it (emphasis added): The NAIRU is a key component of potential output and as such critically affects output gap estimates.

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

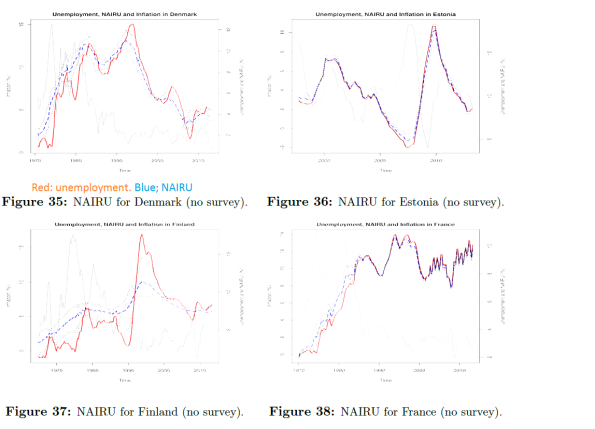

Below, three sets of graphs from three ‘structural’ seconomic tudies which show that the celebrated concept of NAIRU, as defined in these general equilibrium models is little more than a complicated running average of the level of estimated unemployment (though, quite unscientific, economics does not even seem to have an agreed upon algorithm to calculate this average). This a consequence of the assumption of these models that unemployment is a voluntary state of existence.

Yesterday, Lars Syll had an interesting post about the nonsense of NAIRU, the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment, as defined in ‘structural macro economic models’. I totally agree but have a little to add. The discussion about NAIRU is not about the interesting relation between unemployment and wages (or even inflation), as proponents state. It is about the relation between unemployment and potential output: when does a government has to stop stimulating demand to prevent runaway inflation? Does this has to happen when unemployment is 3%? Or when unemployment is 4%? Or as the European commission wanted to have it when unemployment is, ahem, 26,6%? The answer is clear: NAIRU won’t give us the answer. Or, as Gechert, Rietzler and Tobler recently stated it (emphasis added):

The NAIRU is a key component of potential output and as such critically affects output gap estimates. In May 2014, the European Commission (EC) changed its specification of the NAIRU for several countries and lowered its NAIRU estimates – in the case of Spain from 26.6% to 20.7% for 2015. To test the dependence of the new NAIRU on unemployment versus structural factors, we run counterfactual simulations applying one-standard deviation shocks to actual unemployment and to the structural variable – real unit labor costs. We find that the NAIRU in its new specification is still largely determined by actual unemployment.

Summarizing: though there clearly does not seem to be any agreed upon way to estimate it, NAIRU unemployment of 20,7% is considered ‘normal’ by NAIRU adepts like the EC, even though the (arbitrary) way to calculate it seems little more than estimating some kind of complicated running average of actual unemployment. Which means that NAIRU estimates fluctuate wildly, depending on the historical epoch and the way they are measured.

I’ll show this by posting three sets of graphs from three studies about NAIRU.

The first set comes from a Master’s Thesis submitted by Liang Tong to Prof. Dr. Wolfgang K. Härdle and Prof. Dr. Weining Wang, ‘NAIRU estimates of 28 EU member states’. It shows that when you apply a model which assumes general equilibrium in the short-term, NAIRU estimates are sometimes not even averages of actual unemployment!

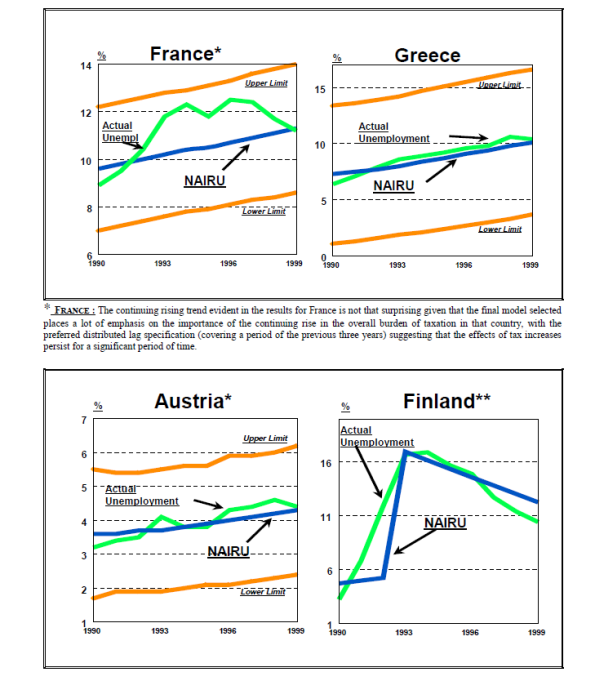

The second comes from an OECD study about NAIRU’s it uses another algorithm than the previous and the next study but it also shows, like the previous and the next study, that historical unemployment differences of as much of 10% of the labour force or more do not matter when you use a complicated way to estimate a running average.

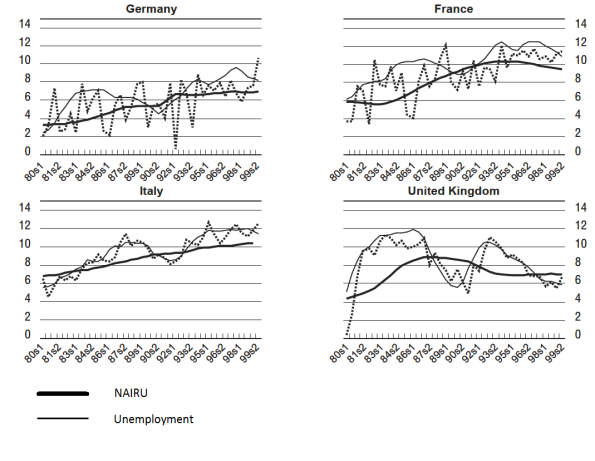

The third study, by Morrow and Roeger who, at least at the time of writing, worked for the EC, estimates TV-NAIRU’s or time varying NAIRU’s which means that it at least admits the existence of a problem. There are some remarks about what might cause the extreme short term and international differences in NAIRU but these are in fact unrelated to the model.

The first set of graphs (note how extreme general equilibrium assumptions make NAIRU coincide with actual unemployment, even if it is sky high):

The second set of graphs. Finland (which experienced a financial crisis) is of course the fun factor here.

The third set of graphs, note that quartely estimates of NAIRU (the dotted line) add lots of ‘noise’, which is logical as wage negotiations often have a yearly rythm).

Somewhat randomly three other points: there are serious studies who point out that an aging population might lead to lower inflation. Also, ‘broad’ unemployment will have an influence on the labour market too, this will have to be taken into account. And taking the consumer price index to calculate NAIRU is daft, as wage levels will influence price levels, albeit not in any kind of mechanical way, but this is also about government production and investments, not just about consumer goods and services.