From David Ruccio It’s obvious to anyone who looks at the numbers that the wage share of national income is historically low. And it’s been falling for decades now, since 1970. Before that, during the short Golden Age of U.S. capitalism, the presumption was that the share of national income going to labor was and would remain relatively stable, hovering around 50 percent. But then it started to fall, and now (as of 2015) stands at 43 percent. That’s a precipitous drop for a supposedly stable share of the total amount produced by workers, especially as productivity rose dramatically during that same period. The question is, what has caused that decline in the labor share? The latest story proffered by mainstream economists (such as David Autor and his coauthors) has to do with “superstar” firms: From manufacturing to retailing, giant companies have managed to gobble up a larger and larger share of the market. While such concentration has resulted in enormous profits for investors and owners of behemoths like Facebook, Google and Amazon, this type of “winner take most” competition may not be so good for workers as a whole. Over the last 30 years, their share of the total income kitty has been eroding. And the industries where concentration is the greatest is where labor’s share has dropped the most. . .

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

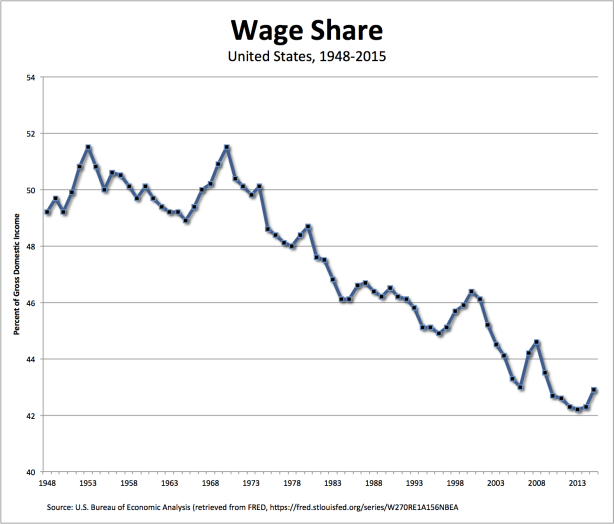

It’s obvious to anyone who looks at the numbers that the wage share of national income is historically low. And it’s been falling for decades now, since 1970.

Before that, during the short Golden Age of U.S. capitalism, the presumption was that the share of national income going to labor was and would remain relatively stable, hovering around 50 percent. But then it started to fall, and now (as of 2015) stands at 43 percent.

That’s a precipitous drop for a supposedly stable share of the total amount produced by workers, especially as productivity rose dramatically during that same period.

The question is, what has caused that decline in the labor share?

The latest story proffered by mainstream economists (such as David Autor and his coauthors) has to do with “superstar” firms:

From manufacturing to retailing, giant companies have managed to gobble up a larger and larger share of the market.

While such concentration has resulted in enormous profits for investors and owners of behemoths like Facebook, Google and Amazon, this type of “winner take most” competition may not be so good for workers as a whole. Over the last 30 years, their share of the total income kitty has been eroding. And the industries where concentration is the greatest is where labor’s share has dropped the most. . .

Think about the retail sector, where mom-and-pop stores once crowded the landscape. Now it is dominated by a handful of giants like Walmart, Target and Costco.

It is true, industry concentration has increased dramatically in recent decades (as I explain here). And the wage share has declined (as illustrated in the chart above).

Here’s the problem: exactly the opposite argument is the one that prevailed in the United States for the earlier period. Economists at the time argued that American workers earned a relatively high share of national income because they worked in concentrated industries, such as cars and steel. Thus, their collectively bargained wages included a portion of the “monopoly rents” captured by the firms within those industries.

Now that the wage share has clearly fallen, and shows no signs of returning to its previous levels, economists have changed their story. In their view, market concentration leads to a lower, not higher, wage share.

Why has there been such an about-face in economists’ story about the causes of the declining wage share?

What all the existing stories share is that they avoid identifying anything that has been done to workers as a class. Whether the story is about technological change, globalization, or now superstar firms, the idea is that there are larger forces that unwittingly have created winners and losers—and the losers, if they want, need to acquire the education and skills to join the winners. But don’t touch the basic elements of the economic system that has created such disparate and divergent outcomes.

As it turns out, the presumed rule of a stable wage share turns out to have been an illusion, an exceptional period of relatively short duration during which workers’ wages did in fact rise along with productivity. That wasn’t the case before, and it hasn’t been true since.

The actual rule, as it turns out, is that the wage share falls, as the rate of exploitation increases. That’s how capitalism works, at least much of the time—through periods of faster and slower technological change, higher or lower levels of globalization, more or less concentrated industries.

Sure, under a particular set of postwar conditions in the United States, for two and a half decades or so, the wage share remained relatively stable (and not without pitched battles between capital and labor, as Richard McIntyre and Michael Hillard have shown). But that ended decades ago, and since then workers have been forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work under conditions that, even as productivity continued to grow, the wage share itself declined.

Mainstream economists have finally recognized the fact that workers’ share of national income has been failing. But they continue to formulate stories that deflect attention from the real problem, the relative immiseration of workers that has them falling further and further behind.