From David Ruccio One of the courses I’m offering this semester is A Tale of Two Depressions, cotaught with one of my colleagues, Ben Giamo, from American Studies. It’s a comparison of the conditions and consequences of the two major crises of capitalism during the past hundred years, the 1930s and the period after the crash of 2007-08.* It just so happens the Guardian is also right now revisiting the 1930s. Readers will find lots of interesting material, from some evocative street photography from the period (including bread lines, hunger marches, and various protests) to classics of political theater (from Bertolt Brecht and Federico García Lorca to John Dos Passos and Clifford Odets). I’ve been writing about the Second Great Depression, in mostly economic terms, since 2010. For the Guardian, the idea is that the situation then, in the 1930s, offers lessons for us today—partly for economic reasons but, increasingly, given the victory of Donald Trump and the growth of other right-wing populist-nationalist movements in Europe, in political terms. Larry Elliott focuses on the economics. Unfortunately, he makes the mistake many commit, by starting with the stock-market crash of 1929—which, as it turns out, was the trigger, but not the cause, of the First Great Depression.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

One of the courses I’m offering this semester is A Tale of Two Depressions, cotaught with one of my colleagues, Ben Giamo, from American Studies. It’s a comparison of the conditions and consequences of the two major crises of capitalism during the past hundred years, the 1930s and the period after the crash of 2007-08.*

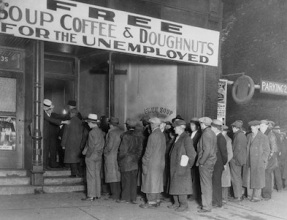

It just so happens the Guardian is also right now revisiting the 1930s. Readers will find lots of interesting material, from some evocative street photography from the period (including bread lines, hunger marches, and various protests) to classics of political theater (from Bertolt Brecht and Federico García Lorca to John Dos Passos and Clifford Odets).

I’ve been writing about the Second Great Depression, in mostly economic terms, since 2010. For the Guardian, the idea is that the situation then, in the 1930s, offers lessons for us today—partly for economic reasons but, increasingly, given the victory of Donald Trump and the growth of other right-wing populist-nationalist movements in Europe, in political terms.

Larry Elliott focuses on the economics. Unfortunately, he makes the mistake many commit, by starting with the stock-market crash of 1929—which, as it turns out, was the trigger, but not the cause, of the First Great Depression. He does a much better job examining the different responses to the two precipitating crashes (yes, there were lessons were learned, especially in the United States, with the quick bailout of Wall Street), including identifying those who were left out of the post-2009 recovery.

Wage increases have been hard to come by, and the strong desire of governments to reduce budget deficits has resulted in unpopular austerity measures. Not all the lessons of the 1930s have been well learned , and the over-hasty tightening of fiscal policy has slowed growth and caused political alienation among those who feel they are being punished for a crisis they did not create, while the real villains get away scot-free . A familiar refrain in both the referendum on Brexit and the 2016 US presidential election was: there might be a recovery going on, but it’s not happening around here. . .

The winners from the liberal economic system that emerged at the end of the cold war have, like their forebears in the 20s, failed to look out for the losers. A rising tide has not lifted all boats, and those who do not consider themselves the beneficiaries of globalisation have grown weary of hearing how marvellous it is.

The 30s are proof that nothing in economics is inevitable. There was eventually a backlash against the economic orthodoxies and Skidelsky can see why there is another backlash happening today. “Globalisation enables capital to escape national and union control. I am much more sympathetic since the start of the crisis to the Marxist way of analysing things.

And then, of course, there’s the political backlash, the topic of the most recent piece in the series. Jonathan Freedland begins by noting the differences between the two periods: the fact that ultra-nationalist and fascist movements managed to seize power in Germany, Italy, and Spain in the 1930s, which has not (yet) happened in the more recent period. Trump, for example, has criticized the media but has not (yet) closed any sites down. Nor has he suggested Muslims wear identifying symbols.

These are crumbs of comfort; they are not intended to minimise the real danger Trump represents to the fundamental norms that underpin liberal democracy. Rather, the point is that we have not reached the 1930s yet. Those sounding the alarm are suggesting only that we may be travelling in that direction – which is bad enough.

There are other warning signs, which suggest closer parallels between the 1930s and today: the shattering of the faith in globalization’s ability to spread the wealth, the growing hostility to those deemed outsiders, and a growing impatience with the rule of law and with democracy. Then, as now, capitalism faces a profound crisis of legitimacy.

In the end, Freedland takes comfort in our having a memory of the 1930s: “We can learn the period’s lessons and avoid its mistakes.” What he fails to acknowledge, however, is that economic and political elites in the 1930s also had vivid memories—of the great crashes of 1873 and 1893 and, of course, the horrors of the “war to end all wars.” But those events were forgotten amidst more short-run memories, including their joining to put down workers’ actions, including the widespread attacks after the 1926 general strike led by the Trades Union Congress in England and the anti-union “American Plan” during the 1920s on the other side of the Atlantic.

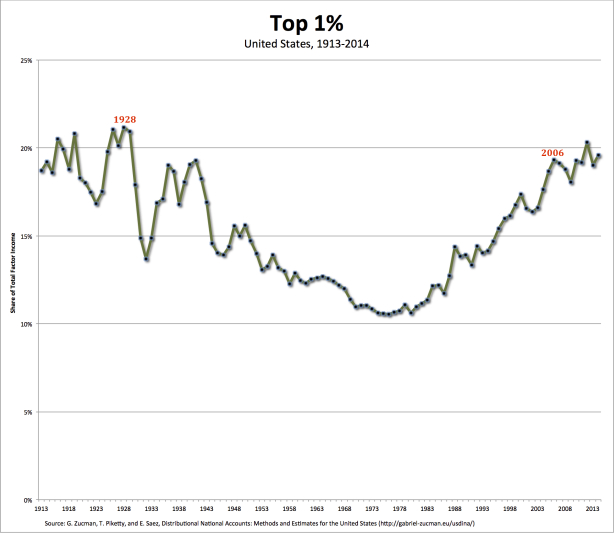

The more or less inevitable result in both countries was growing inequality, as large corporations and a tiny group of wealthy individuals at the top managed to capture a larger and larger share of national income—thus creating a financial bubble that eventually crashed, in 1929 just as in 2007-08.

The memory of the 1929 crash certainly didn’t prevent the most recent one, nor did it create a recovery that has benefited the majority of the population. In fact, it seems the only lesson learned was how it might be possible, in recent years, for those at the top to recovery more quickly than they managed to do after the First Great Depression what they had lost.

It’s that rush to return to business as usual, characterized by obscene levels of inequality, and not the lack of memory of the 1930s, that has created the conditions for the growth and strengthening of populist, right-wing movements in the United States and Europe.

*As is my custom, the syllabus is publicly available on the course web site. Readers might find the large collection of additional materials—music, charts, videos, and so on—of interest. They can be found by following the News link.