From David Ruccio It is likely, if some version of Trump/Ryancare is approved in the United States, millions more people will not be able to purchase the insurance necessary to receive adequate healthcare. The problem is, the United States is already an outlier when it comes to the relationship between health expenditures and health outcomes—measured in this case by life expectancy. As Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser explain, all countries in this graph have followed an upward trajectory (life expectancy increased as health expenditure increased), but the U.S. stands out as an exception following a much flatter trajectory; gains in life expectancy from additional health spending in the U.S. were much smaller than in the other high-income countries, particularly since the mid-1980s. Even more worrisome, higher incomes in the United States are associated with greater longevity, and differences in life expectancy across income groups have increased over time. As Raj Chetty et al. (pdf) discovered, Higher income was associated with longer life throughout the income distribution. Men in the bottom 1% of the income distribution at the age of 40 years had an expected age of death of 72.7 years. Men in the top 1% of the income distribution had an expected age of death of 87.3 years, which is 14.6 years (95% CI, 14.4- 14.8 years) longer than those in the bottom 1%.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

It is likely, if some version of Trump/Ryancare is approved in the United States, millions more people will not be able to purchase the insurance necessary to receive adequate healthcare.

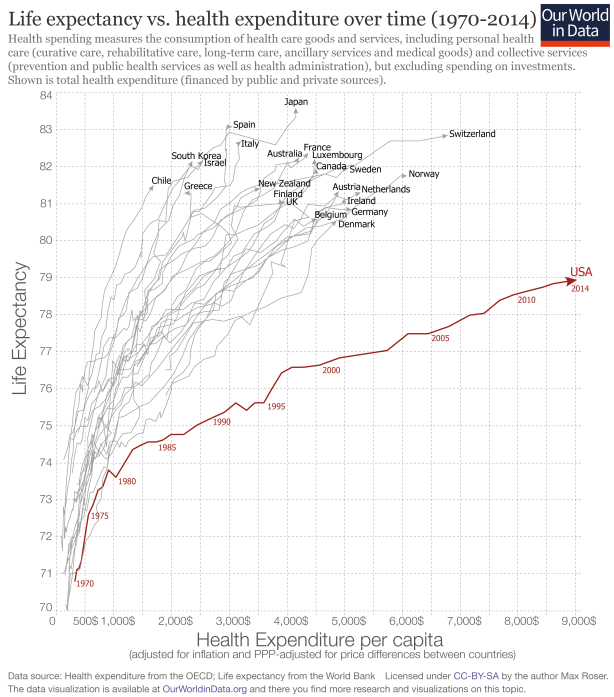

The problem is, the United States is already an outlier when it comes to the relationship between health expenditures and health outcomes—measured in this case by life expectancy.

As Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser explain,

all countries in this graph have followed an upward trajectory (life expectancy increased as health expenditure increased), but the U.S. stands out as an exception following a much flatter trajectory; gains in life expectancy from additional health spending in the U.S. were much smaller than in the other high-income countries, particularly since the mid-1980s.

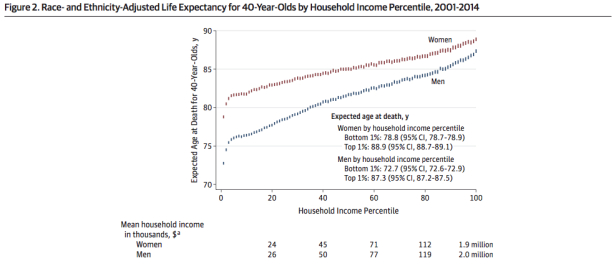

Even more worrisome, higher incomes in the United States are associated with greater longevity, and differences in life expectancy across income groups have increased over time.

As Raj Chetty et al. (pdf) discovered,

Higher income was associated with longer life throughout the income distribution. Men in the bottom 1% of the income distribution at the age of 40 years had an expected age of death of 72.7 years. Men in the top 1% of the income distribution had an expected age of death of 87.3 years, which is 14.6 years (95% CI, 14.4- 14.8 years) longer than those in the bottom 1%. Women in the bottom 1% of the income distribution at the age of 40 years had an expected age of death of 78.8 years. Women in the top 1% had an expected age of death of 88.9 years, which is 10.1 years (95% CI, 9.9-10.3 years) longer than those in the bottom 1%.

As a result, the average life expectancy of the lowest income classes in America is now equal to that in Sudan or Pakistan.

And, with Trump/Ryancare, that class difference in life expectancy is only going to get worse.