From David Ruccio source First, it was conspicuous consumption. Then, it was conspicuous philanthropy. Now, apparently, it’s conspicuous productivity. According to Ben Tarnoff, the acquisition of insanely expensive commodities isn’t the only way that modern elites project power. More recently, another form of status display has emerged. In the new Gilded Age, identifying oneself as a member of the ruling class doesn’t just require conspicuous consumption. It requires conspicuous production. If conspicuous consumption involves the worship of luxury, conspicuous production involves the worship of labor. It isn’t about how much you spend. It’s about how hard you work. And that makes a lot of sense, for at least two reasons. First, CEO salaries in the United States continue to be much higher than average workers’ pay—276 times as much in 2015. CEOs need to publicize the long hours they work in order to attempt to justify the large gap between what they take home and what they pay their workers. As Tarnoff explains, “In an era of extreme inequality, elites need to demonstrate to themselves and others that they deserve to own orders of magnitude more wealth than everyone else.” The problem, of course, is many American workers are working long hours these days.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

First, it was conspicuous consumption. Then, it was conspicuous philanthropy. Now, apparently, it’s conspicuous productivity.

According to Ben Tarnoff,

the acquisition of insanely expensive commodities isn’t the only way that modern elites project power. More recently, another form of status display has emerged. In the new Gilded Age, identifying oneself as a member of the ruling class doesn’t just require conspicuous consumption. It requires conspicuous production.

If conspicuous consumption involves the worship of luxury, conspicuous production involves the worship of labor. It isn’t about how much you spend. It’s about how hard you work.

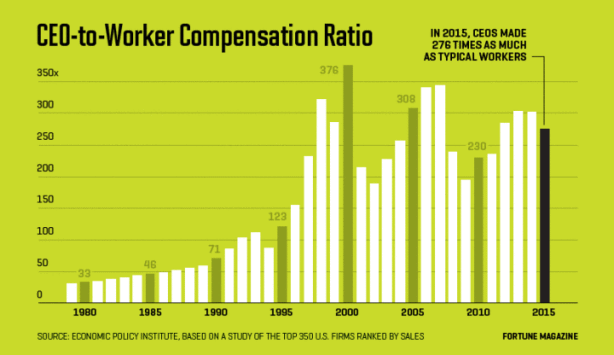

And that makes a lot of sense, for at least two reasons. First, CEO salaries in the United States continue to be much higher than average workers’ pay—276 times as much in 2015. CEOs need to publicize the long hours they work in order to attempt to justify the large gap between what they take home and what they pay their workers. As Tarnoff explains, “In an era of extreme inequality, elites need to demonstrate to themselves and others that they deserve to own orders of magnitude more wealth than everyone else.”

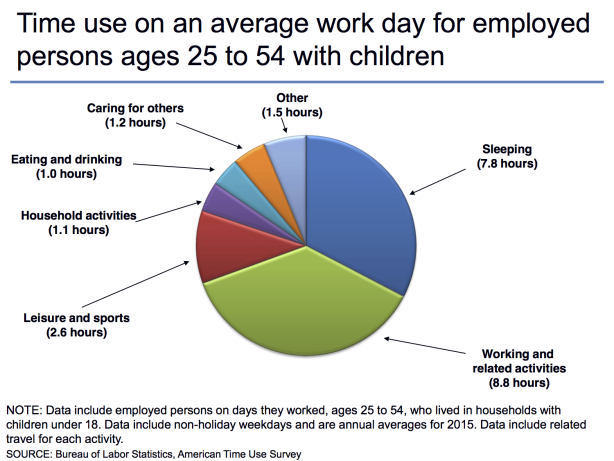

The problem, of course, is many American workers are working long hours these days. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2015, employed persons ages 25 to 54, who lived in households with children under 18, spent an average of 8.8 hours working or in work-related activities and the rest sleeping (7.8 hours), doing leisure and sports activities (2.6 hours), and caring for others, including children (1.2 hours ).

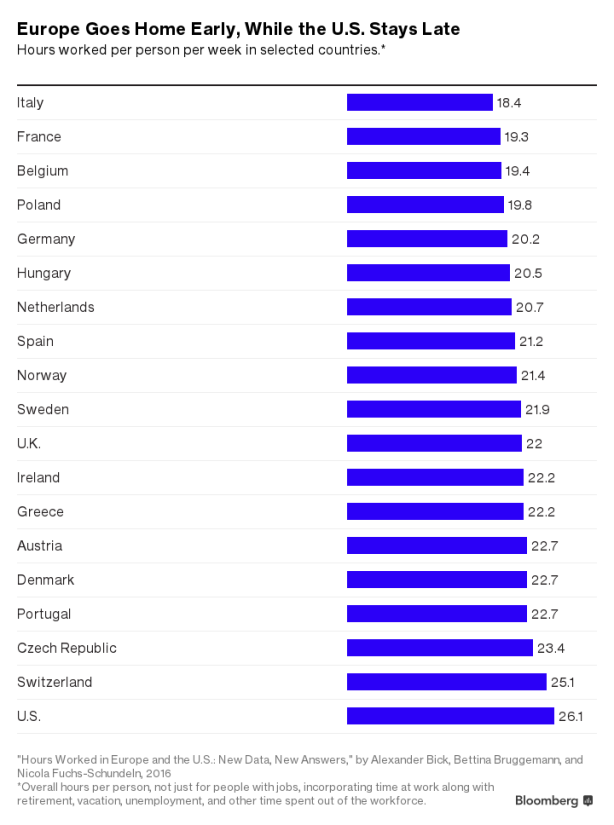

And, on a weekly basis (taking into account public holidays, annual leaves, and so on), U.S. workers put in almost 25 percent more hours—or about an hour more per workday—than Europeans.

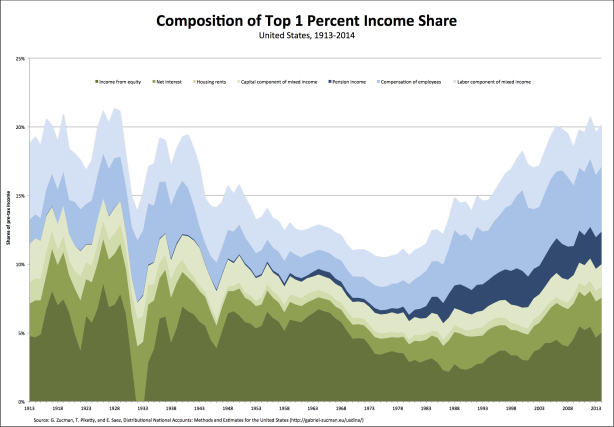

The other reason why conspicuous productivity matters is because, in comparison to the First Gilded Age (when Thorstein Veblen first invented the term conspicuous consumption), a larger share of the surplus captured by the top 1 percent takes the form of labor income during the Second Gilded Age. They get—and deserve—that large and growing share because they work long hours.

The problem, of course, as I showed the other day, that composition of income has changed since 2000. Since then, the capital share of their income has bounced back. Thus, the “working rich” of the late-twentieth century are increasingly living off their capital income, or are in the process of being replaced by their offspring who are living off their inheritances.

This was my conclusion:

It looks then as if those at the top have either turned into or been replaced by rentiers, thus joining the existing owners of capital at the very top—thereby mirroring, after a short interruption, the structure of inequality last seen during the first Gilded Age.

That’s perhaps why conspicuous productivity was invented. Increasingly, those at the top are able to capture a large share of the surplus not because they do, but because they own. But if they can hide that by boasting about the long hours they work, they can attempt to defend their class power.

Or so they hope. . .