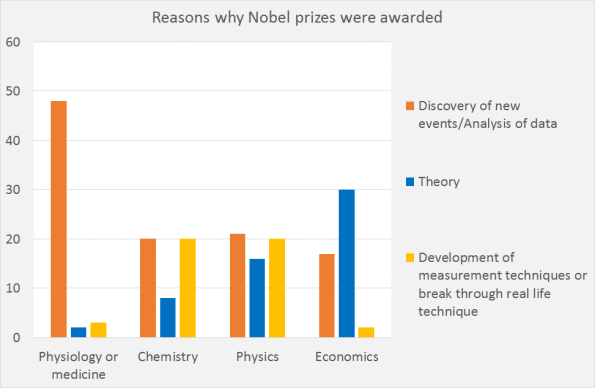

The ‘The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel’ has much more often than the prizes for physics, Chemistry and physiology and medicine been awarded for: theory. It was on a regular basis awarded for analysis of data or the discovery of new events but in these cases ‘discovery’ was contrary to the other sciences much less important than analysis. It was only rarely awarded for the development of measurement techniques. I’m preparing what might become a book about the relation between measurement and theory in economics. In Science, there should, ideally, be a joint development of theory and measurements. To me it seems that in economics this joint development is, though not entirely absent, wanting. A referee suggested that I had to should make a

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

The ‘The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel’ has much more often than the prizes for physics, Chemistry and physiology and medicine been awarded for: theory. It was on a regular basis awarded for analysis of data or the discovery of new events but in these cases ‘discovery’ was contrary to the other sciences much less important than analysis. It was only rarely awarded for the development of measurement techniques.

I’m preparing what might become a book about the relation between measurement and theory in economics. In Science, there should, ideally, be a joint development of theory and measurements. To me it seems that in economics this joint development is, though not entirely absent, wanting. A referee suggested that I had to should make a comparison with other sciences which triggered me to do something which had been in the back of my mind for some time already: making a comparison of why Nobel prizes were awarded in different sciences. I started in 1969 (when Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen were awarded their Riksbank prize for economics and used sites like this one to investigate the reasons why the prizes were awarded. On the sites it was often stated why prizes were awarded (theory, development, analysis and discovery were words often used), when in doubt I did a little (not much, that means) Wikipedia research. In the end I chose three broad categories: theory, development of means or systems of measurement and of breakthrough technologies and discovery of new events; sometimes it was necessary to assign a prize to two categories (especially when there were multiple winners). It turned out that there were quite some differences between the four sciences; the graph clearly shows that economics is (in fact; was as this metric shows past research) indeed quite theory dominated.

This might be related to the nature of economics – the graph also shows that the physiology and medicine price is almost completely dominated by ‘discoveries’ (might it be that live is more complicated than the universe?). It might also be more political, at least in economics. Edward Fullbrook states that sciences are delineated by fundamental differences between what is measured and hence by fundamentally different systems of measurement (here and more fundamentally here). A large hadron collider is not the same thing as the system of national accounts. Which means that the decisions about what is measured are about the heart and soul of a science. Look here for a blogposts which discusses the politics (as well as the practical aspect) behind the fact that experimental economics (randomized control trials) almost always looks at private and not at public goods and services. This might indeed mean that economists as well as the people awarding the prizes chose to life in a world of make believe, inhabited by drones and clones, instead of the real world (sounds crude, but ‘rational expectations’ is the idea that everybody a-priori expects exactly what the economist wants them to expect). There is also a more mundane explanation: Nobel prizes have to be awarded to people. Not to institutions. And much of the thinking and development connected with (macro-)economic measurement takes place in institutions. Which do not get prizes. Which means that we might need a second ‘Nobel’ prize for economics, for institutions like the International Labor Organization, the French INSEE or the USA BLS. Especially in the age of Trump.

Anyway – there is a difference between economics and the other sciences shown here. It is, surprisingly, much more theoretical.