From David Ruccio At one time, from the late-1970s until the last couple of years, Britain—or at least the British ruling class—was in love with neoliberalism. Neoliberalism was the common sense of both major political parties—the Tories and Labor (plus, the Conservative coalition partner Liberal Democrats)—as well as most large corporations and wealthy individuals. As Andy Beckett explains, In the early years of the 21st century, the inevitability of an ever more competitive, deregulated, internationally orientated market economy, to which both government and society were subordinate – a doctrine often called neoliberalism – was accepted right across the mainstream of British politics: from the Thatcherites who still dominated the Conservative party; to the increasingly

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

At one time, from the late-1970s until the last couple of years, Britain—or at least the British ruling class—was in love with neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism was the common sense of both major political parties—the Tories and Labor (plus, the Conservative coalition partner Liberal Democrats)—as well as most large corporations and wealthy individuals.

As Andy Beckett explains,

In the early years of the 21st century, the inevitability of an ever more competitive, deregulated, internationally orientated market economy, to which both government and society were subordinate – a doctrine often called neoliberalism – was accepted right across the mainstream of British politics: from the Thatcherites who still dominated the Conservative party; to the increasingly pro-business Liberal Democrats, who would soon form a coalition government with the Tories; to the Scottish National party, whose then leader Alex Salmond praised Ireland and Iceland for their low corporate taxes; to the Blair cabinet itself, where, I was told by a senior Labour figure in 2001, “You won’t find a single member with anything critical to say about capitalism.” It was assumed by the main parties that most voters felt the same way.

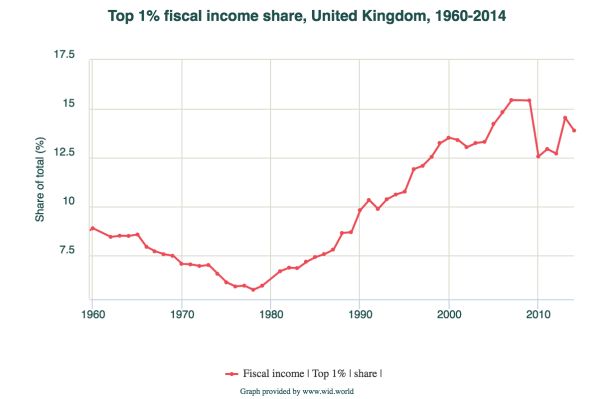

Much the same was true in the United States, from the presidency of Jimmy Carter onward.And British neoliberalism worked, at last for the tiny group at the top. The share of income captured by the top 1 percent more than doubled, rising from 5.7 percent in 1978 to 15.4 percent in 2007.

Just as the worst set of crises of capitalism since the first Great Depression broke out.

It’s taken a decade but now, as Beckett explains, Britain has fallen out of love with neoliberalism.

Here’s the problem: the rejection of neoliberalism, at least among the elite, seems to follow the same market-versus-state logic as previous crises of free-market capitalism.

If Mariana Mazzucato—”favourite contemporary economist” of Labor’s John McDonnell—is any guide, the pendulum is shifting once again toward the state.* Free-market capitalism is being challenged by a more state-enabled form of capitalism.

Once again, they’re sticking to the market-versus-state terms of debate we’ve seen since capitalism first emerged. When forms of capitalism oriented around private ownership and free markets are declared to have failed, they turn to more government intervention and more state-regulated forms of capitalism.

Back and forth. Between market and state, the individual and society. Between micro and macro, neoclassical economics and Keynesian economics.

As I wrote just about this time last year,

The fact is, capitalism has been governed by many different (incomplete and contested) projects over the past three centuries or so. Sometimes, it has been more private and oriented around free markets (as it has been with neoliberalism); at other times, more public or state oriented and focused on regulated markets (as it was under the Depression-era New Deals and during the immediate postwar period).

However, in both cases, the goal has been to extract surplus-value from workers, within and across countries. While criticisms of neoliberalism tend to emphasize the problems created by individualism and free markets, they forget about or overlook the problems—at both the micro and macro levels—associated with class exploitation.

Once we direct our focus to those problems, concerning the conditions and consequences of appropriating and distributing the surplus, the issue is not what kind of better capitalism we can put in place, but what alternatives to capitalism can be imagined and created.

The challenge right now, in Great Britain as in the United States, is to break that market-versus-state dichotomy and use all that we know about forms of noncapitalism to create more equalizing, democratic, and sustainable forms of economy and society.

*See also Mazzucato’s 2016 Prebisch Lecture, on “The Entrepreneurial State: Implications for Market Creation and Economic Development.”