From David Ruccio The election and administration of Donald Trump have focused attention on the many symbols of racism and white supremacy that still exist across the United States. They’re a national disgrace. Fortunately, we’re also witnessing renewed efforts to dethrone Confederate monuments and other such symbols as part of a long-overdue campaign to rethink Americans’ history as a nation. In economics, the problem is not monuments but the discipline itself. It’s the most disgraceful discipline in the academy. Therefore, we should dethrone ourselves. In the United States, thanks to the work of the Southern Poverty Law Center, we know there are over 700 monuments and statues to the Confederacy, as well as scores of public schools, counties and cities, and military bases named for

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The election and administration of Donald Trump have focused attention on the many symbols of racism and white supremacy that still exist across the United States. They’re a national disgrace. Fortunately, we’re also witnessing renewed efforts to dethrone Confederate monuments and other such symbols as part of a long-overdue campaign to rethink Americans’ history as a nation.

The election and administration of Donald Trump have focused attention on the many symbols of racism and white supremacy that still exist across the United States. They’re a national disgrace. Fortunately, we’re also witnessing renewed efforts to dethrone Confederate monuments and other such symbols as part of a long-overdue campaign to rethink Americans’ history as a nation.

In economics, the problem is not monuments but the discipline itself. It’s the most disgraceful discipline in the academy. Therefore, we should dethrone ourselves.

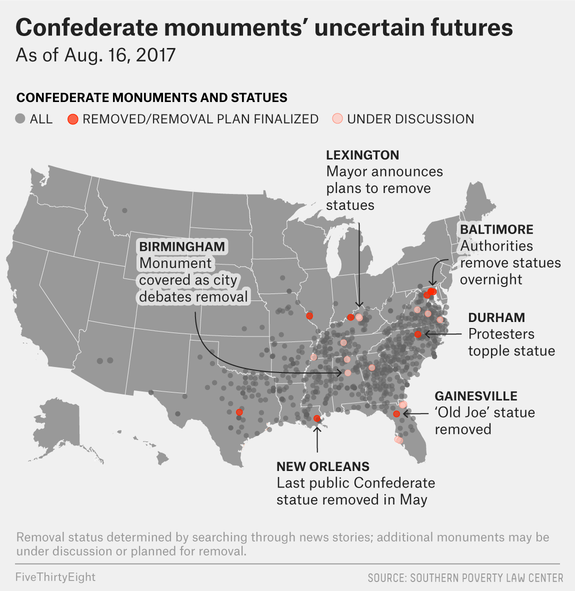

In the United States, thanks to the work of the Southern Poverty Law Center, we know there are over 700 monuments and statues to the Confederacy, as well as scores of public schools, counties and cities, and military bases named for Confederate leaders and icons.

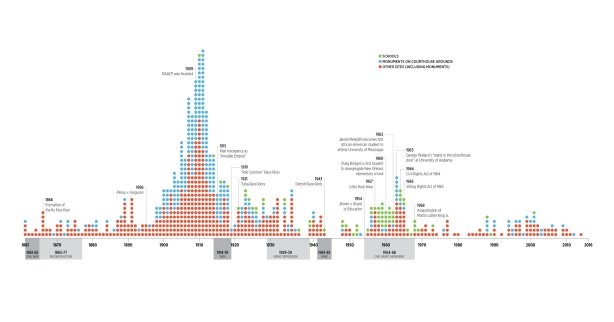

We also know those symbols do not represent any kind of shared heritage but, instead, conceal the real history of the Confederate States of America and the seven decades of Jim Crow segregation and oppression that followed the Reconstruction era. In fact, most of them were dedicated not immediately after the Civil War, but during two key periods in U.S. history:

The first began around 1900, amid the period in which states were enacting Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise the newly freed African Americans and re-segregate society. This spike lasted well into the 1920s, a period that saw a dramatic resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been born in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War.

The second spike began in the early 1950s and lasted through the 1960s, as the civil rights movement led to a backlash among segregationists. These two periods also coincided with the 50th and 100th anniversaries of the Civil War.

The problem, of course, is those statues have stayed up for so long because, like so many other features of our everyday landscape, they became so familiar that Americans hardly even noticed they were there.

It should come as no surprise, then, that a majority of Americans (62 percent) believe statues honoring leaders of the Confederacy should remain. However, a similar majority (55 percent) said they disapproved of the Trump’s response to the deadly violence that occurred at a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville. As a result, I expect Americans will be engaged in a new conversation about their history—especially the most disgraceful episodes of slavery, white supremacy, and racism—and what those symbols represent today.

The discipline of economics has a similar problem—not of statues but of sexism and hostility to women. It’s been so much a feature of our everyday academic landscape that economists hardly even noticed it was there.

They didn’t notice until reports surfaced—in the New York Times and the Washington Post—concerning Alice Wu’s senior thesis in economics at the University of California-Berkeley. Wu analyzed over a million posts on the anonymous online message board, Economics Job Market Rumors, to analyze how economists talk about women in the profession.

According to Wu,

Gender stereotyping can take a subtle or implicit form that makes it difficult to measure and analyze in economics. In addition, people tend not to reveal their true beliefs about gender if they care about political and social correctness in public. The anonymity on the Economics Job Market Rumors forum, however, removes such barriers, and thus provides a natural setting to study the existence and extent of gender stereotyping in this academic community online.

And the results of her analysis? The 30 words most associated with women were (in order, from top to bottom): hotter, lesbian, bb (Internet terminology for “baby”), sexism, tits, anal, marrying, feminazi, slut, hot, vagina, boobs, pregnant, pregnancy, cute, marry, levy, gorgeous, horny, crush, beautiful, secretary, dump, shopping, date, nonprofit, intentions, sexy, dated, and prostitute.

In contrast, the terms most associated with men included mathematician, pricing, adviser, textbook, motivated, Wharton, goals, Nobel, and philosopher. Indeed, the only derogatory terms in the list were bully and homo.

In my experience, that’s a pretty accurate description of how women and men are unequally seen, treated, and talked about in economics—and that’s been true for much of the history of the discipline.*

But, of course, that’s not the only reason economics is the most bankrupt, disgraceful discipline in the entire academy. It has long shunned and punished economists who endeavor to use theories and methods that fall outside mainstream economics—denying jobs, research funding, publication outlets, and honorifics to their “colleagues” who have the temerity to teach and do research utilizing other discourses and paradigms, from Marxism to feminism.

Even the attempt to convince economists to adopt a code of ethics—like those in many other disciplines, from anthropology to medicine—was treated with disdain.

Sure, there’s a Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. And, in the United States, both a Council of Economic Advisers and a National Economic Council—but no White House Council of Social Advisers.

Economics may have national and international prominence. But it’s time we give up the hand-wringing and admit there is no standard of decency or intelligence (with the possible exception of mathematics) that economists don’t fail on.

We are, in short, a collective disgrace. That’s why we should dethrone ourselves.

*A history that includes Joan Robinson, who should have won the Nobel Prize in Economics but didn’t (because, of course, she was a non-neoclassical, female economist) and can’t (because she’s dead).