From David Ruccio “When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” “The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” “The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.” Alice in Wonderland (pdf) is the key to understanding much of what is happening in the world today—especially the language of economics. For example, we’re going to hear and read a great deal about tax reform in the days and weeks ahead. But, based on the proposals I’ve seen, nothing in the way of tax reform is being proposed. The usual meaning of reform is that it involves changes for the better. Most of the so-called reforms that are being proposed by the Trump

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

Alice in Wonderland (pdf) is the key to understanding much of what is happening in the world today—especially the language of economics.

For example, we’re going to hear and read a great deal about tax reform in the days and weeks ahead. But, based on the proposals I’ve seen, nothing in the way of tax reform is being proposed.

The usual meaning of reform is that it involves changes for the better. Most of the so-called reforms that are being proposed by the Trump administration—including the vague speech by Donald Trump yesterday—are just cuts in the tax rates that will directly benefit wealthy individuals and large corporations.

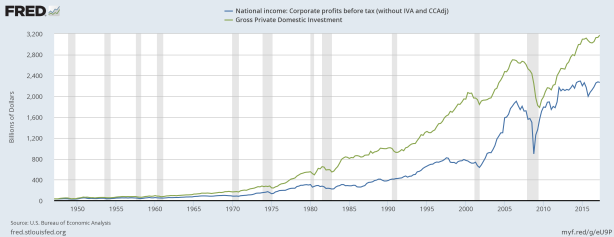

Supposedly, the rest of us will eventually benefit because of increased investment. However, as is clear from the chart above, both corporate profits and private domestic investment are doing just fine without a cut in tax rates. But the benefits to the rest of us simply haven’t appeared.

Moreover, as I have explained before, U.S. corporations are not losing out in the competitive battle with foreign corporations because they face tax rates that are much too high.

And, no, as I have also explained, repatriating corporate profits will not lead to more investment, government revenues, and jobs.

In fact, as Patrician Cohen makes clear, the whole idea of repatriating profits held abroad makes no sense.

That’s because repatriation is not really about geography. Most of the money is not stashed in some underground vault overseas, but already in American financial institutions and capital markets. Repatriation is in effect a legal category that requires a company to book the money in the United States — and pay taxes on it — before it can be distributed to shareholders or invested domestically.

The whole notion of earnings trapped offshore is misleading, Steven M. Rosenthal, a tax lawyer and senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “The earnings are not ‘trapped,’” he said. “They’re not offshore. They’re not even earnings. They’re accounting gimmicks that allow earnings to be shifted abroad.”

What’s more, companies already get something akin to tax-free repatriation by borrowing against those funds, with the added bonus of being able to deduct the interest paid on those loans from their tax bill.

What if corporations are induced to book their overseas profits in the United States? We probably won’t see much if any increase in private investment, since corporations aren’t facing any kind constraint in profits or their ability to borrow beyond their current profits. What is much more likely is some combination of more mergers and acquisitions, more stock buybacks, more payouts to shareholders, and more compensation distributed to CEOS.*

And that’s going to lead to even more inequality in the United States.

Alice surely would have seen through the meanings of all these misleading words concerning tax reform.

*AT&T is a good example of a company that already passes a low effective tax rate by exploiting tax breaks and loopholes. However, according to Sarah Anderson,

Despite the enormous savings AT&T has realized, the company has been downsizing. Although it hires thousands of people a year, the company, by our analysis at the Institute for Policy Studies, reduced its total work force by nearly 80,000 jobs between 2008 and 2016, accounting for acquisitions and spinoffs each involving more than 2,000 workers.

The company has also spent $34 billion repurchasing its own stock since 2008, according to our institute report, a maneuver that artificially inflates the value of a company’s shares. This is money that could have gone toward research and development or hiring.

Companies buy back their stock for various reasons — to take advantage of undervaluation, to reward stockholders by increasing the value of their shares or to make the company look more attractive to investors. And there is another reason. Because most executive compensation these days is based on stock value, higher share prices can raise the compensation of chief executives and other top company officials.

Since 2008, [AT&T CEO Randall] Stephenson has cashed in $124 million in stock options and grants.

Many other large American corporations have also been playing the tax break and loophole game. Their huge tax savings have enriched executives but not created significant numbers of new jobs.

Boeing is another good example. As Justin Miller explains,

Boeing has received a tax refund in five of the past ten years. It saves itself $542 million a year using a special domestic manufacturing tax break, and $1.8 billion in further cuts thanks to a research and development tax credit. Boeing also benefits from the immensely favorable depreciation schedules on capital that has saved it billions of dollars over the past decade.

Boeing also entered into a $9 billion tax incentive deal with Washington state back in 2013—the largest corporate subsidy ever—to “maintain and grow its workforce within the state.” But, as Michael Hiltzik points out in the Los Angeles Times, the company has since cut nearly 13,000 jobs (about 15 percent of its Washington workforce) as it sets up shop in cheaper states that offer incentives of their own.

It still manages to enrich its shareholders though. On the same day that it announced a production slowdown in December, Hiltzik notes, Boeing also announced a 30 percent increase in its quarterly dividend and a new $14 billion share-buyback program.