From David Ruccio We’ve been hearing this since the recovery from the Second Great Depression began: it’s going to be a Golden Age for workers! The idea is that the decades of wage stagnation are finally over, as the United States enters a new period of labor shortage and workers will be able to recoup what they’ve lost. The latest to try to tell this story is Eduardo Porter: the wage picture is looking decidedly brighter. In 2008, in the midst of the recession, the average hourly pay of production and nonsupervisory workers tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics — those who toil at a cash register or on a shop floor — was 10 percent below its 1973 peak after accounting for inflation. Since then, wages have regained virtually all of that ground. Median wages for all full-time

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

We’ve been hearing this since the recovery from the Second Great Depression began: it’s going to be a Golden Age for workers!

The idea is that the decades of wage stagnation are finally over, as the United States enters a new period of labor shortage and workers will be able to recoup what they’ve lost.

The latest to try to tell this story is Eduardo Porter:

the wage picture is looking decidedly brighter. In 2008, in the midst of the recession, the average hourly pay of production and nonsupervisory workers tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics — those who toil at a cash register or on a shop floor — was 10 percent below its 1973 peak after accounting for inflation. Since then, wages have regained virtually all of that ground. Median wages for all full-time workers are rising at a pace last achieved in the dot-com boom at the end of the Clinton administration.

And with employers adding more than two million jobs a year, some economists suspect that American workers — after being pummeled by a furious mix of globalization and automation, strangled by monetary policy that has restrained economic activity in the name of low inflation, and slapped around by government hostility toward unions and labor regulations — may finally be in for a break.

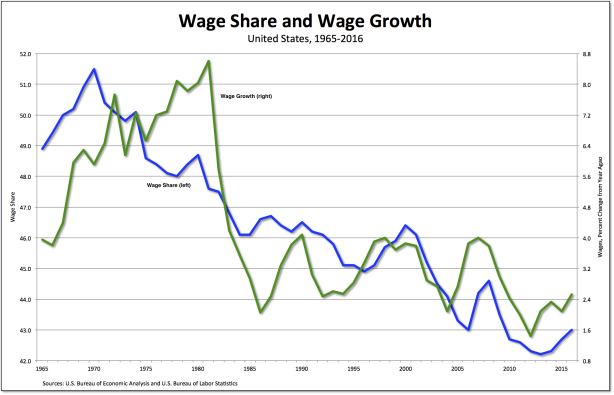

The problem is that wages are still growing at a historically slow pace (the green line in the chart above), which means the wage share (the blue line in the chart) is still very low. The only sign that things might be getting better for workers is that the current wage share is slightly above the low recorded in 2013—but, at 43 percent, it remains far below its high of 51.5 percent in 1970.

That’s an awful lot of ground to make up.

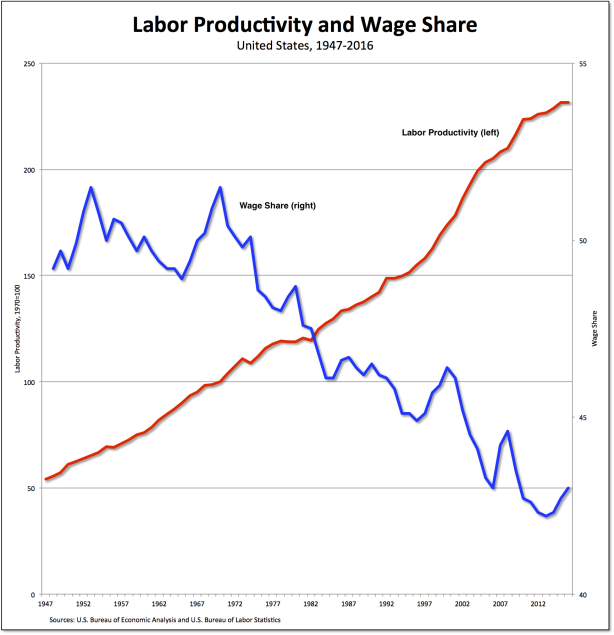

The situation for American workers is even worse when we compare labor productivity and the wage share. Since 1970, labor productivity (the real output per hour workers in the nonfarm business sector, the red line in the chart above) has more than doubled, while the wage share (the blue line) has fallen precipitously.

We’re a long way from any kind of Golden Age for workers.

But, in the end, that’s not what Porter is particularly interested in. He’s more concerned about what he considers to be a labor shortage caused by a shrinking labor force.

So, what does Porter recommend to, in his words, “protect economic growth and to give American workers a shot at a new golden age of employment”? More immigration, more international trade, cuts in disability insurance, and limiting increases in the minimum wage.

Someone’s going to have to explain to me how that set of policies is going to reverse the declines of recent decades and usher in a Golden Age for American workers.