From David Ruccio The world joined most South Africans in cheering when Nelson Mandela was finally released from prison, the apartheid regime was largely dismantled, and multiracial elections were eventually held. Then, of course, the really hard work of restorative justice began, under the aegis of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. To avoid victor’s justice, no side was exempt from appearing before the commission, which heard reports of human rights violations and considered amnesty applications from all sides. In the end, the commission granted only 849 amnesties out of the 7,112 applications. The problem is, while the commission exposed human rights abuses, it never took up the issue of economic abuses. And, as is clear from the chart above, the high levels of inequality

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The world joined most South Africans in cheering when Nelson Mandela was finally released from prison, the apartheid regime was largely dismantled, and multiracial elections were eventually held.

Then, of course, the really hard work of restorative justice began, under the aegis of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. To avoid victor’s justice, no side was exempt from appearing before the commission, which heard reports of human rights violations and considered amnesty applications from all sides. In the end, the commission granted only 849 amnesties out of the 7,112 applications.

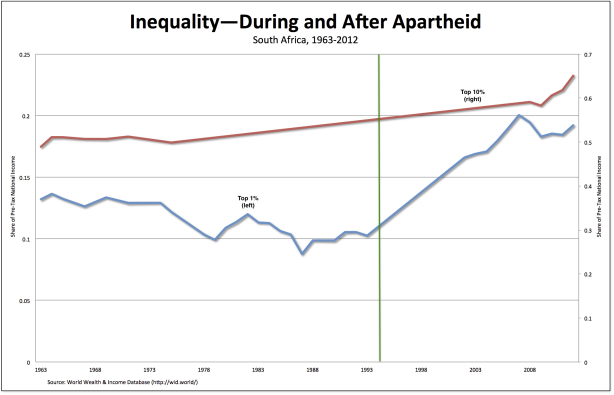

The problem is, while the commission exposed human rights abuses, it never took up the issue of economic abuses. And, as is clear from the chart above, the high levels of inequality that characterized South African capitalism under apartheid have only gotten worse.

The share of income captured by the top 1 percent (the blue line in the chart) rose from 10.3 percent in 1993 to 19.2 percent in 2012, while the share captured by the top 10 percent (the red line) was 65 percent.*

It should come as no surprise that the distribution of wealth is even more unequal than the distribution of income. Anna Orthofer (pdf) has surveyed the available data and calculated that the top 1 percent own at least half of all wealth in the country and the 10 percent something like 90 to 95 percent.

That’s why Peter Goodman correctly observes that

In the history of civil rights, South Africa lays claim to a momentous achievement — the demolition of apartheid and the construction of a democracy. But for black South Africans, who account for three-fourths of this nation of roughly 55 million people, political liberation has yet to translate into broad material gains.

Apartheid has essentially persisted in economic form.

Thus far, the existing economic system has been granted a full amnesty.

The day awaits for a new Truth and Reconciliation Commission to be formed, to carry out the project of finding restorative justice with respect to the abuses of the economic system—both during and now after apartheid.

*For purposes of comparison, the top 1-percent share in the United States in 2012 was 20.3 percent and that of the top 10 percent was 47.6 percent.