From David Ruccio How bad have things gotten in the United States? Nitin Nohria [ht: ja], the dean of Harvard Business School, is sounding the alarm that “class lines. . .have become far more distinct and visible in recent years.” Nohria published his essay at the end of the same week that the U.S. Senate passed its version of the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” which is nothing more than an enormous boon to large corporations and wealthy individuals under the guise of trickledown economics, and Philip Aston, the United Nations monitor on extreme poverty and human rights, has embarked on a coast-to-coast tour to investigate the widespread existence of extreme poverty in the United States. The inspiration for Nohria’s reference to class lines is Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

How bad have things gotten in the United States? Nitin Nohria [ht: ja], the dean of Harvard Business School, is sounding the alarm that “class lines. . .have become far more distinct and visible in recent years.”

Nohria published his essay at the end of the same week that the U.S. Senate passed its version of the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” which is nothing more than an enormous boon to large corporations and wealthy individuals under the guise of trickledown economics, and Philip Aston, the United Nations monitor on extreme poverty and human rights, has embarked on a coast-to-coast tour to investigate the widespread existence of extreme poverty in the United States.

The inspiration for Nohria’s reference to class lines is Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land (which we taught in the spring, as the final text of A Tale of Two Depressions). According to Hochschild, the U.S. class structure once resembled an orderly queue: the premise and promise of economic and social institutions were that, if you worked hard, you would achieve the American Dream.

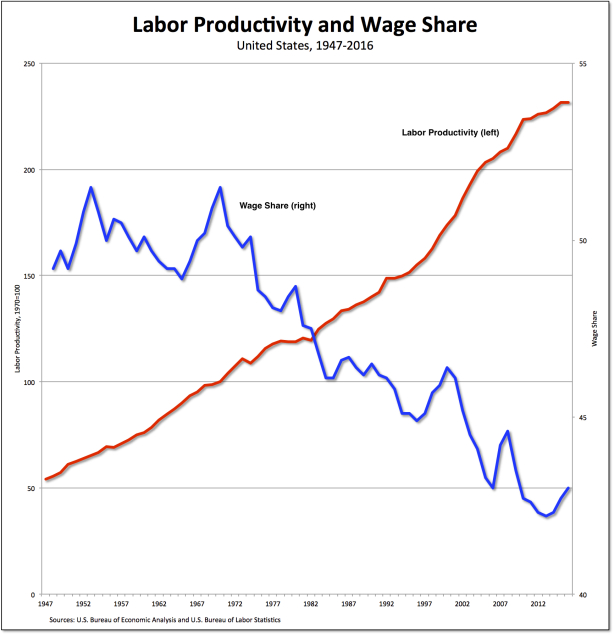

Notwithstanding the large number of exceptions (for racial and ethnic minorities, impoverished whites, women, and many others), it was a story Americans told about themselves and their country. And it held a kernel of truth: until the mid-1970s, workers’ wages did keep pace with growing productivity.

Now, of course, the American Dream lies in tatters. The members of the white working-class in Hochschild’s account are resentful that others at the bottom—especially minorities and immigrants—have been allowed, with the help of the government, to cut head of them in the line.

Nohria goes in a different direction:

As I read Hochschild’s analysis, my thoughts turned to a different sort of resentment the white working class is feeling. Even as it stews over people cutting into its ever slower-moving line, it also envies another faster-moving queue: the special one reserved for people with means—the ones who travel business or first class. The affluent people in this line believe they have earned their preferred status through a meritocratic process that has assessed and rewarded their ambition and enterprise. This group becomes accustomed to its special privileges and comes to expect them everywhere, from legacy admissions to college for their children to special seating at sports events to VIP treatment at theme parks. It begins to believe that there should be a special line for innovators and pioneers who have sacrificed time with friends and family to achieve their personal best—those who want to reach for the top, to be number one. Yet even preferred status is not enough; those on any fast track can always see a still-faster track. If the first-class line is short, flying on a private aircraft from a terminal with no security lines is even faster.

The result is that

Now there are fewer and fewer opportunities for people in different lines to ever encounter each other in person. They go to different schools, shop at different stores, and rarely interact. Yet they are hyper-aware of each other due in part to the ubiquity of social media and television. You can gawk at the lives of the privileged on Instagram, tap into the resentment of the white working class on Brietbart [sic], and see the plight of the disenfranchised on Vice. This ready visibility has unleashed a range of emotions, including resentment, entitlement, envy, and despair—and it’s tearing America apart.

Neither Hochschild nor Nohria offers an analysis of why those class lines are moving further and further apart—there’s no mention of how more and more surplus is being captured and kept by the small group at the top. And Nohria’s proposed solution, to allow more underprivileged students into Harvard Business School and to expose all business students to “cases that describe the challenges of the working class and the impoverished,” is derisorily inadequate.

In my view, we don’t need yet another effort “to better understand those who may not be in the same line as us.” What we need instead is an open and frank discussion of how the existing economic and social institutions in the United States are predicated on creating and reproducing those class lines—and how a different set of institutions would erase the class lines that keep Americans apart.

Let’s see them teach that lesson at Harvard Business School.