John Taylor edited the new 2000+ pages plus ‘Handbook of macro-economics’, effectively a ‘Handbook of neoclassical macroeconomics’. Neoclassical economics is known for its illicit use of garbled language which hides and convolutes instead of explains. As the title of the book exemplifies. An interesting example is the chapter by Edward Prescott, titled ‘RBC Methodology and the Development of Aggregate Economic Theory’ (ungated version). Let’s first give the floor to him (emphasis added), mind that ‘leisure’ means ‘measured unemployment’.: “What turned out to be the big breakthrough was the use of growth theory to study business cycle fluctuations … based on micro theory reasoning, dynamic economic theory was viewed as being useless in understanding business cycle fluctuations. This

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

John Taylor edited the new 2000+ pages plus ‘Handbook of macro-economics’, effectively a ‘Handbook of neoclassical macroeconomics’. Neoclassical economics is known for its illicit use of garbled language which hides and convolutes instead of explains. As the title of the book exemplifies. An interesting example is the chapter by Edward Prescott, titled ‘RBC Methodology and the Development of Aggregate Economic Theory’ (ungated version). Let’s first give the floor to him (emphasis added), mind that ‘leisure’ means ‘measured unemployment’.:

“What turned out to be the big breakthrough was the use of growth theory to study business cycle fluctuations … based on micro theory reasoning, dynamic economic theory was viewed as being useless in understanding business cycle fluctuations. This view arose because, cyclically, leisure and consumption moved in opposite directions. Being that these goods are both normal goods and there is little cyclical movement in their relative price, micro reasoning leads to the conclusion that leisure should move procyclically when in fact it moves strongly countercyclically. Another fact is that labor productivity is a procyclical variable; this runs counter to the prediction of micro theory that it should be countercyclical, given the aggregate labor input to production. Micro reasoning leads to the incorrect conclusion that these aggregate observations violated the law of diminishing returns. In order to use growth theory to study business cycle fluctuations, the investment-consumption decision and the labor-leisure decision must be endogenized. Kydland and Prescott (1982) introduced an aggregate household to accomplish this. We restricted attention to the household utility function for which the model economies had a balanced growth path, and this balanced growth path displayed the growth facts. With this extension, growth theory and business cycle theory were integrated. It turned out that the predictions of dynamic aggregate theory were consistent with the business cycle facts that ran counter to the conclusion of those using microeconomic reasoning”

Translation: “Depressions are caused because people want to work less. Yes, we measure unemployment and it goes up when spending declines. But by assuming a ‘balanced growth path’ we define this away: the growth path is by assumption balanced so no unemployment exists and what we measure is leisure, not unemployment. People (sorry, ‘the representative consumer’) sometimes suddenly want to work a lot less, hence 25% unemployment (sorry, leisure) in countries like Greece and Spain and during the Great Depression in the USA. Hey, problem solved (and f*** the statistics)!”

You might think that this is this translation is too far fetched. it’s not. So, let’s give the floor to Prescott once more. From the same article, emphasis added

“Cole and Ohanian (1999) initiated a program of using the theory to study great depressions. They found a big deviation from the theory for the 1930–1939 US Great Depression. This deviation was the failure of market hours per working-age person to recover to its pre-depression level. Throughout the 1930s, market hours per working-age person were 20 to 25 percent below their pre-depression level. The reasons for depressed labor supply were not financial. No financial crises occurred during the period 1934–1939. The period had no deflation, and interest rates were low. This led Cole and Ohanian to rule out monetary policy as the reason for the depressed labor supply. Neither was the behavior of productivity the reason. Productivity recovered to trend in 1934 and subsequently stayed near the trend path.”

This is a garbled use of the phrase ‘labor supply’ as it does not include the (idle) hours of the unemployed in the numerator while including the unemployed in de denominator. Clearly, the unemployed are according to Prescott not part of the labour supply. Only hours actually worked are part of the labour supply (when it comes to the numerator). This goes against everything scientific economics has to offer about this. According to official terminology, defined by the International Labour Organization, the unemployed as we measure them (and not just they) are part of this supply:

“Furthermore, the unemployment rate is not a comprehensive measure of the potential supply of labour. While it aims to capture a very specific target group for policy-making purposes, it does not cover all persons with an unmet need for income-generating work.”

Mind that the economists measuring unemployment define it as people actively seeking income-generating activities. Mind that 90% of the unemployed in Greece do not get welfare. Mind that people who have to count as unemployed do not have one single hour of paid employment. And they are according to official economic terminology but also based upon common sense and our knowledge of history, part of aggregate labour supply (emphasis added). Using an official phrase like ‘labour supply’ in a scientific article in a garbled way which clearly contradicts its official, historical and common sense meaning is, in a scientific sense, illicit.

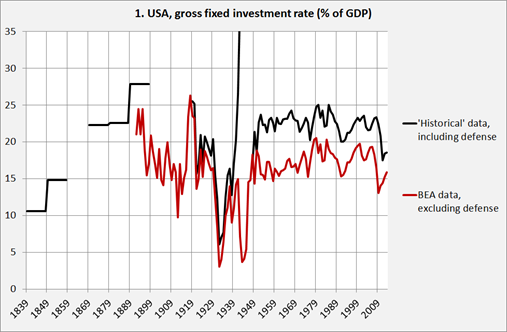

The graph shows what really happened in the USA during the Great Depression: investments declined with about 15% of GDP. Which lead to widespread unemployment and idle fixed capital. Labour supply did not decline, labour demand did. To compensate this, government expenditure or household consumption had to increase with 15% of GDP. This would have meant more than a doubling of (federal) expenditure in the USA. An increase of household consumption with about 20 to 25% would also have done the job, but that does not easily happen after an employment declines of about 20 percent. During World War II, USA government expenditure finally increased with the necessary amount and, lo and behold, unemployment vanished. The additional labour was one of the reasons why the USA was able to ramp up production at a rate of around 15% a year for several years in a stretch. Which, again, shows how wrong Prescott is: people really, really wanted to work and the economy was totally able to provide employment.

There is more to this. Unemployment (for nerds: the U-3 definition) as statisticians measure it on the individual level has a nominal scale. The unemployment rate can be expressed as a percentage of the total population and has an interval scale with a ‘unique and non-arbitrary’ point zero but this is not the same variable as unemployment at the individual level. Assuming a representative individual while at the same time assuming that the unemployment scale for this assumed individual is not a nominal but an interval scale is in fact assuming a non-representative individual. Water has a freezing point, an individual H2O molecules hasn’t. A swimming pool is not a representative H2O molecule.

Prescott also makes a whole lot of other mistakes:

- when productivity recovers to trend this does not mean that production recovers to trend. Historically, the 20% of GDP growth rates of USA production during World War II show that in the thirties, GDP was clearly below trend).

- even within the logic of these models (which use a ‘natural rate of interest’) a historically low interest rate does not mean that this rate is low compared to the model equilibrium rate is low. The model rate is by definition the rate which returns unemployment to a low level which means that monetary policy can be blamed, again using the logic of these models.

- ”no financial crisis occurred during the period 1934-1939’. So? It is well-known that recovery after financial crises can last for a decade, if not longer. Which means that the banking crises of the years before 1934 might well have cast a shadow beyond 1934.

- The same holds for deflation. Surely when the price level has decreased a lot (which is what happened) it might require a lot of time before inflation works its wonders.

Convoluted economics expressed in a convoluted language.