Back in November I invited a local solar installation company round to my house to take a look at the roof. I hadn’t expected it to be a money tree, but I was still surprised and disappointed when the quote came in. It would take 16 years to earn back a solar investment on my south-facing roof. I reassured myself; once it had paid itself back I’d start reaping a healthy 6.2% on my investment. Then, researching for this post, the picture got worse. While a solar panel can last up to 30 years, the government’s ‘Feed-in Tariff’ (FiT), which subsidises small-scale renewable energy, only applies for the first 20. My

Topics:

neweconomics considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

Back in November I invited a local solar installation company round to my house to take a look at the roof. I hadn’t expected it to be a money tree, but I was still surprised and disappointed when the quote came in. It would take 16 years to earn back a solar investment on my south-facing roof.

I reassured myself; once it had paid itself back I’d start reaping a healthy 6.2% on my investment. Then, researching for this post, the picture got worse. While a solar panel can last up to 30 years, the government’s ‘Feed-in Tariff’ (FiT), which subsidises small-scale renewable energy, only applies for the first 20. My return would drop to 4.4%. I was starting to wonder if there was a financial case for citizen solar at all. In the end, it didn’t matter. Last week I phoned the company back and found out they’d gone bust.

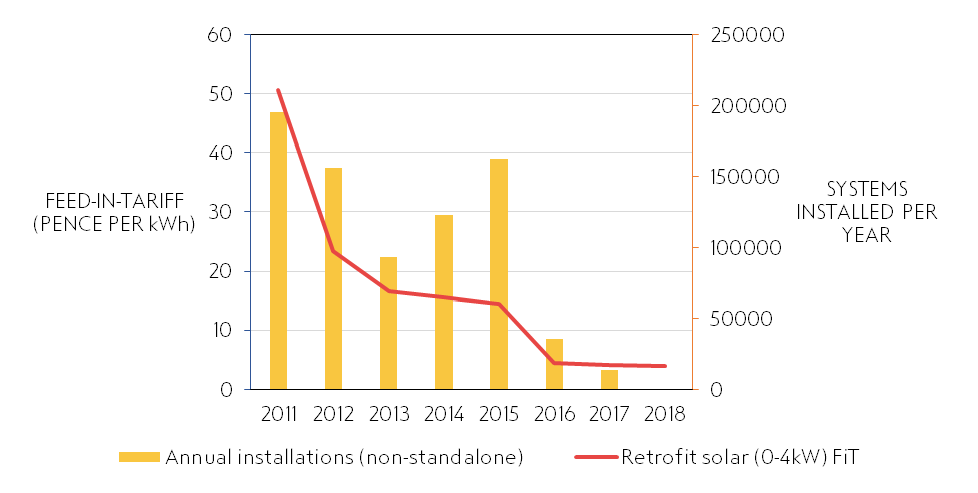

After a quick glance at the government’s latest solar statistics it was easy to see why. The number of new installations per month has plunged from an average of over 9,000 between 2010 and 2016, to under 1,000 at the end of 2017. The decline correlates with the Government’s slow suffocation of the Feed-in-Tariff over the last seven years (see figure below). When these changes were being prepared, the government were made well aware of the (now proven) consequences, yet stubbornly decided to proceed.

A friend in a local solar power company sourced their struggles not just in the Government’s attack on the FiT, but also to the (connected) rise in ‘tokenistic’ solar installations in new housing developments. Most local authorities, and the local development plans they are creating, are now requiring developers to link new homes to some form of renewable energy scheme (see for example Policy SC1 of Plan:MK). Some developers opt for solar, but are able to satisfy their legal obligations with only one or two panels. Not only are these small jobs bad business for solar power companies, they are far less efficient than panelling a full roof due to the carbon debt associated with the installation process. Below is a photo of a scheme I cycled past in Milton Keynes – that looks like a lot of wasted roof space!

Some back-of-the-envelope maths: there are around 28 million residential properties in the UK. If we make a conservative estimate that a third of them have optimally oriented and shaped roofs, and a few have planning restrictions, then the UK has around 9 million properties ready for solar panels. There is enough potential in just the residential market (never mind commercial and public space) to more than double solar’s current contribution (3.4%) to our national electricity generation. Currently, only around 800,000 homes – that’s 9% – actually have them. At our current installation rate it would take more than 600 years for us to put panels on every suitable house in the UK.

It’s issues like this that have led the Committee on Climate Change to conclude that we are on course to miss our legally binding emissions reduction targets. The UK, one of the world’s richest economies, is not contributing enough to the global effort on climate change.

At our current installation rate it would take more than 600 years for us to put panels on every suitable house in the UK.

It’s easy to forget the connection between residential solar panels and the human cost of climate change. To take just one example, I have written before about climate change driving thousands of people out of their homes in Southern Vietnam. This includes members of a community I visited in 2013, whose crops are repeatedly blighted by salt intruding into the soil as the sea-level rises. Last month the United Nations reiterated its warning that we are pushing the climate down a path which leads to hundreds of millions of migrants being forced to leave degraded lands.

Solar costs are continuing to fall. One day, they won’t need subsidy, and that day is coming ever closer. But the urgency to act on climate change, coupled with the opportunity to be a world-leader make every ounce of delay nonsensical. Unfortunately, Earth’s climate can’t wait for so-called market forces, as my friends in Vietnam can attest. As well as bringing the FiT back to a level sufficient to incentivise citizen solar the government needs to be more proactive in assembling the market architecture which will support a large distributed solar network, including long-term solutions for selling and storing excess generation.

So what does all this tell us about the Government’s broader environmental agenda? There is apparently a new ‘war on plastic’ being waged, with the latest idea being for England to get a deposit return scheme, and the Government consulting on a plastic tax. But amongst all this we can’t let energy generation fall by the wayside. If Ministers want to demonstrate their seriousness about tackling our environmental challenges, they must commit to action on both plastics and energy supply, and not scupper it before it leaves the port.

Alex Chapman is a Consultant at NEF Consulting

NEF Consulting has conducted work showing the economic benefits of community-based adaptation to climate change, and its effects in Dakoro, Niger