Having purchased healthcare, automotive, etc. components from various molding manufacturers, I can definitely testify to the amount of scrap created from each part. There is no way of avoiding the scrap left from a molded component. Much of this ends up in regrind and what ever is sorted may go into other uses. The story touches on micro particles occurring during the regrinding of the scrap. Some so small, it is difficult to see. The little-known unintended consequence of recycling plastics, Washington Post, Allyson Chu. Breaking down plastics can generate polluting microplastics winding up in water or the air, one study finds. Instead of helping to tackle the world’s staggering plastic waste problem, recycling may be exacerbating a

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: recycling, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

Having purchased healthcare, automotive, etc. components from various molding manufacturers, I can definitely testify to the amount of scrap created from each part. There is no way of avoiding the scrap left from a molded component. Much of this ends up in regrind and what ever is sorted may go into other uses. The story touches on micro particles occurring during the regrinding of the scrap. Some so small, it is difficult to see.

The little-known unintended consequence of recycling plastics, Washington Post, Allyson Chu.

Breaking down plastics can generate polluting microplastics winding up in water or the air, one study finds.

Instead of helping to tackle the world’s staggering plastic waste problem, recycling may be exacerbating a concerning environmental problem called microplastic pollution.

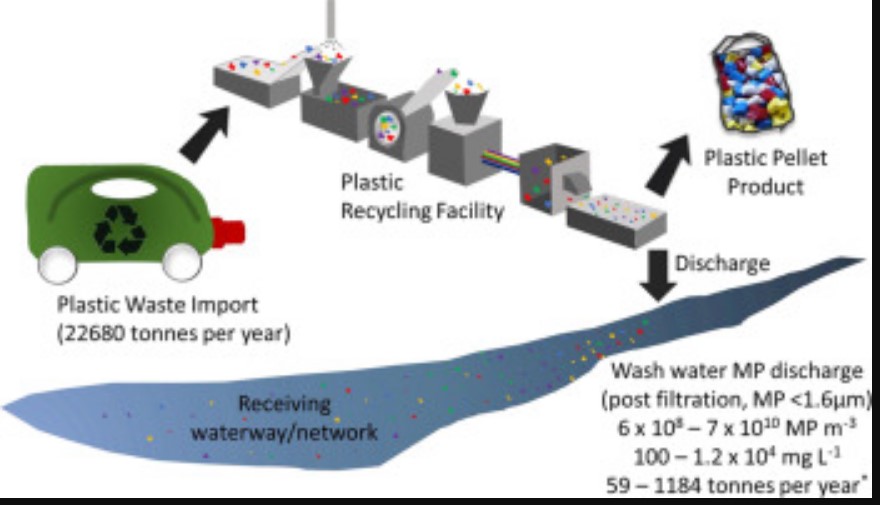

A recent peer-reviewed study focused on a recycling facility in the United Kingdom suggests anywhere between 6 to 13 percent of the plastic processed could end up being released into water or the air as microplastics. Ubiquitous tiny particles smaller than five millimeters that have been found everywhere from Antarctic snow to inside human bodies. Erina Brown, a plastics scientist who led the research while at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland.

“This is such a big gap that nobody’s even considered, let alone actually really researched,”

The research adds to growing concerns recycling isn’t as effective of a solution for the plastic pollution problem as many might think. Only a fraction of the plastic produced gets recycled. About 9 percent worldwide and about 5 to 6 percent in the United States, according to some recent estimates.

The study was conducted at a single plastic recycling facility, but experts say its findings shouldn’t be taken lightly. Judith Enck, a former senior Environmental Protection Agency official under President Barack Obama who now heads the Beyond Plastics advocacy organization.

“It’s a very credible study. (She was not involved in the research). It’s only one facility, but it raises troubling issues, and it should inspire environmental regulatory agencies to replicate the study at other plastic recycling facilities.”

How does plastic recycling work?

While there are many different types of plastic, many experts say only things made out of No. 1 and 2 are really recycled effectively in the United States. At recycling facilities, plastic waste is generally sorted, cleaned, chopped up or shredded into bits, melted down and remolded.

It’s not surprising this process could produce microplastics, Enck said. “The way plastic recycling facilities operate, there’s a lot of mechanical friction and abrasion,” she said.

Brown and other researchers analyzed the bits of plastic found in the wastewater generated by the unnamed facility. They estimated it could produce up to 6.5 million pounds of microplastic per year, or about 13 percent of the mass of the total amount of plastic the facility receives annually.

The researchers also found high amounts of microplastic when they tested the air at the facility, Brown said.

Will filters help?

The study also looked at the facility’s wastewater after filters were installed. With filtration, the estimate of microplastics produced dropped to about 3 million pounds a year.

The microplastic pollution mitigation (filtration installed) was found to remove the majority of microplastics >5µm, with high removal efficiencies for microplastics >40µm. Microplastics <5µm were generally not removed by the filtration and subsequently discharged, with 59-1184 tonnes potentially discharged annually. It is recommended that additional filtration to remove the smaller microplastics prior to wash discharge is incorporated in the wash water management. Evidence of microplastic wash water pollution suggest it may be important to integrate microplastics into water quality regulations. Further studies should be conducted to increase knowledge of microplastic pollution from plastic recycling processes.

The potential for a plastic recycling facility to release microplastic pollution and possible filtration remediation effectiveness, ScienceDirect, Erina Brown, Anna MacDonald, Steve Allen, Deonie Allen.

Even with the use of filters at the plant, the researchers estimated that there were up to 75 billion plastic particles per meter cubed in the facility’s wastewater. A majority of the microscopic pieces were smaller than 10 micrometers, about the diameter of a human red blood cell, with more than 80 percent below five micrometers, Brown said.

She noted that the recycling facility studied was “relatively state-of-the-art” and had elected to install filtration. “It’s really important to consider that so many facilities worldwide might not have any filtration,” she said. “They might have some, but it’s not regulated at all.”

While effective filters could help, Brown and other experts believe they are not the solution.

“I don’t think we can filter our way out of this problem,” Enck said.

More research and better regulation

Enck and other plastics experts not involved in the research said it underscores the need to look into the issue more deeply. Anja Brandon, associate director of U.S. plastics policy at Ocean Conservancy, a nonprofit group.

“The findings are certainly alarming enough that it’s worthy of far more investigation and understanding of how widespread of an issue this might be.”

Unlike other ways microplastic can wind up in the environment, recycling facilities could be identifiable sources, Brandon said.

“We know where the pollution is coming . . . and we could take measures to actually do something about it through permitting, through regulation, through all of those kind of rules we have available. This is an area we could take action on, provided we learn a little bit more.”

Many of the environmental permitting requirements in the United States are based on decades-old standards that should be updated to reflect with “the best available science,” she added.

Kara Pochiro, a spokesperson for the Association of Plastic Recyclers, an international trade association, said plastic recycling plants do not all have the same water treatment system as the U.K. facility that was studied. But recyclers, she said, are subject to national, state and local regulations, including environmental laws. Adding . . .

“Every plastics recycling facility works closely with their local municipal plant, including sampling and third-party testing at mutually agreed upon intervals.”

The Environmental Protection Agency said it will review the study.

Keep recycling

Despite the study’s findings, experts emphasized that the answer isn’t to stop recycling. Anja Brandon . . .

“What this study does not tell us . . . is that we should stop recycling plastic. So long as we are continuing to use plastic, mechanical recycling is really the best end-of-life scenario for these materials to keep us from needing to produce more and more plastic.”

Plastic waste that isn’t reused or recycled generally ends up in landfills or incinerated, Enck said. It’s important, she and other experts said, for people to continue to try reducing the amount of plastic they use.

“This is not a major reason why we have such a significant problem with microplastics in the environment,” she said. “But it’s potentially part of it and there’s an irony to it because it involves recycling.”