What follows is a summary of what I see as the key advice, with links to other resources that go into more depth or do a better job than I can. It’s going to be most accurate for economics, political science, public policy & other professional schools This post is a continuous work in progress, and it is comes not only from my own experience but that of a huge number of colleagues and readers. It can benefit from your feedback too, so please email me if a you have something to add (or if you see a broken link). The big stuff The quality of research typically matters more than the quantity, and this is especially true with a job market paper. If you’re within six to nine months of the job market, the marginal return to investing in your job market paper is almost always higher than

Topics:

Chris Blattman considers the following as important: academia, Advice: PhDs, Economics, job market, political science, public policy

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

What follows is a summary of what I see as the key advice, with links to other resources that go into more depth or do a better job than I can. It’s going to be most accurate for economics, political science, public policy & other professional schools

This post is a continuous work in progress, and it is comes not only from my own experience but that of a huge number of colleagues and readers. It can benefit from your feedback too, so please email me if a you have something to add (or if you see a broken link).

The big stuff

- The quality of research typically matters more than the quantity, and this is especially true with a job market paper.

- If you’re within six to nine months of the job market, the marginal return to investing in your job market paper is almost always higher than investment in any other paper. This is the paper that search committees will read most carefully, and the one piece of research that every faculty member will see and use to shape their impression of you.

- I repeat some advice given to me the year I was on the job market: from now until you have a job, work on your job market paper 25 hours a day, 8 days a week, 5 weeks a month.

- But remember that most people will only look at the abstract and introduction, and perhaps the conclusion and tables. The whole job market paper has to be polished to a gleam, but these sections have to be perfect. Get as many colleagues as possible to give you feedback. If you ask someone to “please read my paper” they may never have the time. But if you say “can you please give me your first reaction to my abstract and intro” you will probably get more feedback.

- Some departments value other publications on your CV. This is especially true in political science. One reason is that political scientists tend to do research in “smaller bites” than economists, something that is also true in psychology and many hard sciences. Having a published paper or two signals you can get things out the door, and are producing like your peers. Nonetheless, as you get close to the job market I seldom advise students to start new projects or trying to polish other papers in order to improve their standing on your CV.

- Maximize the amount of input and support you get from your advisors and department.

- Make sure you are meeting with your committee members early and often.

- Discuss your job market aspirations and plans early, and ask for their frank advice on what you should be looking at.

- These relationships are so important because your recommendation letters will make an enormous difference in the job interviews you get. Once you’ve been chosen for an interview, it’s all up to you to demonstrate your quality and fit. Before that, academic employers will look at your recommendation letters to guide them on whether to invite you out.

- Apply more widely than your first instinct, partly because there is a lot of idiosyncrasy in the academic job market, and partly because you probably underestimate how attractive some jobs are, or how good the fit.

- After a job market search, I think most people would tell you that they learned a lot about the jobs and were often surprised by the new information. The lesson: chances are you don’t know enough about any particular job to judge how good or bad it is.

- A job ad might look like the perfect job, but departments will have all sorts of unobservable information (budget constraints, subject or diversity needs, departmental in-fights, methodological hangups, veto players, etc.) that mean the chances of an interview, let alone a job, are very low.

- Also, there are some cities and schools where you might say, “I can’t imagine ever going there” or “I’ve never heard of that place”, but on arrival you will very surprised about how good the colleagues are and how pleasant the lifestyle.

- Also, you don’t want to insult a school by declining to visit. If there are personal or other reasons why you could not take a job there (e.g. an existing job offer you would likely take elsewhere), then it is fine to be up front about that and frame it in terms of not wanting to waste their valuable time. Handle this delicately with input from colleagues/advisors.

- These are the best reasons to send applications to as many positions as possible.

- It is seldom a good idea to go on a “limited market” and apply to a few choice programs. Besides lowering your overall odds of a job, your odds of competing offers, and hence a good salary or teaching deal, plummets. And first offers are highly path dependent.

- This is all about finding the best fit.

- Places that don’t value the kind of work you do will probably not interview you, and if they interview you and decide you’re not a good fit, that’s good news for you. You don’t want to invest a lot of time or energy in a place that doesn’t share you interests or contribution.

- Remember that most departments are not just looking to hire someone who works on topic X, but to hire a colleague they enjoy talking to and learning from, and who will be a voice of reason not insanity in their department.

- Be strategic but not too strategic. You can try to shape your work to appeal to certain types of departments or schools, but I discourage this for a couple of reasons. First it’s hard to know what other people want. Second you will probably be better at what you do, and happier, if you’re doing what you love.

- So take some comfort in the fact that “it’s endogenous” and the job market bends towards matching you happily. Work passionately and diligently and become the expert in your field, who’s work influences the profession, and the rest will work itself out.

- Don’t hang your job market hopes on academic positions outside your core discipline.

- Your main market will be the discipline you got your PhD in, so keep this in mind when you write up your dissertation, letters, and applications.

- For example, if you are an economist, you will face many hurdles in jobs in political science. Also, there are relatively few business and policy schools, and they seem to have relatively few junior openings.

- If you have a PhD from a professional school, your best market is probably other professional schools and (if you study political topics and have political scientists as advisors) political science. Economics departments seldom hire non-economics PhDs. But you have a natural advantage in policy, education, health and other professional schools partly because you have signaled your interest in these policy-relevant, interdisciplinary places with your PhD.

- You are probably unlike your professors, and that’s fine.

- Most PhD programs are in top schools, and the professors in those departments are probably self-selected to have a particular set of passions and interests, work-life balance (or lack thereof), postponement of family life, and so on.

- The PhD has in large part been about socializing you to adopt the same preferences, and your self-esteem and the esteem of many of your colleagues is wrapped up in meeting these expectations.

- That said, the broader academic world includes a much more heterogeneous group of people, including ones who care deeply about teaching or public service or family and personal life.

- There are also many interesting policy and industry careers. Some thoughts on these below.

- You should consider this in choosing a job. Pick the kind of place and environment that matches your preferences, and that allows you to be evaluated on the same things that create your self worth.

Academic job market timetable

Application deadlines for North American universities are typically late August for political science, and November for economics. Professional schools recruiting a political scientist or economist usually follow the market cycle of the discipline they want.

Here is a very detailed timeline for the US market. Some UK and European schools follow this market (like LSE), but there is a lot of variation, and you should read Thomas Leeper’s advice if you are considering this market.

Below is a rough timetable for preparing for the market, working back from the date applications are due. Where necessary I indicate specific advice for economics (E) and political science (PS).

- 9-12 months before applications are due:

- You should have a topic that you think is job market worthy and have made a fair degree of progress

- Your advisers should share your optimism, and you should have discussed with them (at least three faculty) that you plan to go on the market.

- It’s not a bad idea to set up a personal website now and clean up your online presence (see advice below).

- 4-6 months before applications:

- You should have a reasonably decent draft of the job market paper that your advisors can comment on (see the advice on writing a job market paper below.)

- For the next few months you should be corresponding with your advisors several times a month and regularly putting together new drafts. Ask your advisors if they think you are ready for the market.

- 2-4 months before applications:

- Present your paper as many times as possible. You may want to make your first presentations inside your department until the work is a little more polished, since first impressions matter.

- Read all the detailed advice out there (under general preparation tips below)

- Start preparing your CV, website (if you don’t have one already), download teaching evaluations from the university, and start early drafts of your cover letter and research/teaching statements. Ask your advisors to read these and comment. See examples and templates below.

- In September, economists should register for the ASSA meetings and book your flight and hotel. These cab go fast!

- Make sure you have practiced your 1-minute and 5-minute explanations of your dissertation work (since people will start asking early) and start preparing for longer interview summaries of your paper.

- 1-2 months before applications:

- If your department does not organize practice job talks and mock interviews, ask for one. Also, consider asking other graduate students (especially friends who recently went on the market) to attend a practice talk or get you through a mock interview.

- Send your materials to your advisors, so they can start writing recommendation letters. Here is what I ask my students to do.

- Check out the “Things to get” below in general preparation advice

- You should be polishing your slides and introduction more than generating new results.

General preparation tips

- Read all the online advice

- Every year John Cawley publishes a guide to the job market for economists that is also useful for other disciplines, and his online posts are useful as well

- Johannes Pfiefer maintains a catalog of job market tip pages and resources, also geared for economists

- The Duck of Minerva blog has a host of job market posts geared for political scientists

- In general, though, political science departments and professional schools don’t seem to condense and publicly share their job market tips. There are useful blog posts out there, however, from Quantitative Peace, Math of Politics, Paul Musgrave, and Mario Guerrero

- Thomas Leeper has excellent advice for the UK and European markets. As does Alexandre Afonso. My one addition: be aware that for various reasons (signaling, social networks, etc.) it is difficult to cross the Atlantic. It is by no means a one way street, but coming back to North America after taking a job abroad adds hurdles to an already hurdle-strewn process.

- Make a short, simple CV and keep it up to date.

- Make it easy for people to find your CV and research online.

- Set up a professional website. If your department sets up a page for you, use it.

- But also consider a personal site that will follow you from institution to institution, and provide a stable domain for all your work in future.

- If you want something extremely simple, try Google Sites.

- Frankly you would be wise to set up a personal site eventually, so why not now? It is fairly straightforward. I recommend buying your own domain name and setting it up with WordPress. Here is an easy guide.

- Employers will Google you, so clean up and organize your online presence.

- Get your professional site placed as highly as possible in search rankings. Ways to do this include:

- Have your university link to it as soon as possible (links from high reputation sites matter) since appearing in rankings can take months

- Have a domain name with your first and last name in the domain, and ideally use .com

- Make your Facebook and other purely personal social media posts as private as possible. If you tweet or use other more public social media, consider making these private, especially if they include potentially unprofessional material.

- Here is a 2012 post from LifeHacker that is not as dated as I would expect. Here is a 2016 CNET post.

- Pay for a professional photo. You will need one anyways once you are working. Or get a friend who is an experienced photographer to take a professional photo.

- Get your Google Scholar profile set up.

- Get your professional site placed as highly as possible in search rankings. Ways to do this include:

- Decide on your academic name.

- You will need to decide whether to use middle initials, the full version of your name, and so forth. Use middle initials to minimize confusion with others. This decision will follow you for the rest of your life so get it right and stay consistent.

- Things to get (shout out to former Chicago students for some of these)

- Flu shot

- A credit card for travel expenses

- Two nice suits and lots of shirts

- You might as well register for airline rewards, picking one airline per alliance to pile your rewards into

- I have advice on what to bring to the sky, more suited for long haul trips than short haul but still worth considering

Your interviews

Economics, political science, and policy schools will all invite 2-4 people to “fly out” for any given junior job posting. This is usually a full day affair where you present your job market paper and meet with faculty. The economics profession begins with “the meetings”: several days of stressful speed dating, to narrow their list of invitees for a fly out.

I won’t repeat the usual wisdom, because so much is documented elsewhere.

The Royal Economic Society has a nice overview of the entire economics process, including advice on interviews. It summarizes several other common advice posts: from Chicago PhD students, Claudia Goldin and David Laibson, and David Levine’s “cheap advice“, among others.

For the political science and professional school markets, I think most of the fly out advice from economists applies. The Duck of Minerva also has a host of post with interview-relevant advice. I welcome other pointers.

Some miscellaneous advice I want to emphasize:

- Be yourself, and try to enjoy yourself. Whether they offer you a job or not, these people are your future colleagues and you will interact with many of them for the next 10 or 20 years at conferences, journals, etc.

- Stay in touch with your advisor and keep him/her appraised of developments on a weekly basis. Use a spreadsheet or Google doc to keep track of where you applied and where things stand.

- Resist the temptation to impress people with how complex your work is. Most of the people voting on whether to hire you are not in your field. Even if they are very smart they will probably not know why your work is important or what it is all about. If you can explain things intuitively and plainly so that all can understand, before launching into the technical wizardry or details, that is for the better.

- Learn to strike a balance between being forthright about the weaknesses of your work (without sounding apologetic) and not being overconfident (and sounding like an ass).

Your job talk

Here are Jesse Shapiro’s amazing slides on presenting applied micro research. I think the principles apply more broadly, and everyone should read them.

Don Davis also has good advice on presenting a paper. David Levine also offers good advice.

I only have one additional piece of advice: Don’t use slide templates that clutter up the screen with titles and authors on every page, or where we are in the presentation, or slide numbers, or crap like that. It helps nobody and communicates nothing.

Negotiating a job offer

I hope all the above advice lands you a job offer. If so, I’ve written about negotiation in a separate post.

The “two-body problem”

Dual career couples are a tough problem to navigate, and every situation is going to be different. A great read for both men and women (regardless of discipline) are the 2014 and 2016 newsletters from the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession.

There are a lot of personal stories in these newsletters, which strikes me as the right way to approach the question, since it depends so much on personal priorities.

I am always on the lookout for other good advice, so please send me any pointers you have.

The elephant in the room

Of all the job market advice I’ve linked to above, almost none of it mentions that the majority of the professors in the department hiring you will probably be white men. This imbalance is especially stark in economics. If you are a woman or person of color, I haven’t told you anything new. But I don’t want to ignore it, or dance around the fact, because I think it’s probably one of the more important problems faced by my fields. I think there’s a better chance of a change if everyone has a better understanding of the issues and it can be talked about openly.

For the moment, I’ve collected the resources and advice posts I’ve been able to find on the Internet, or that have been recommended to me. These are useful for everyone to read (I gained a lot). More suggestions by email are welcome.

There are a handful of curated groups from the discipline:

There’s also a range of personal essays and opinions:

Professional schools

Since so much of the existing advice applies is written by economists and political scientists for their own departments, I collect here some general advice that I think probably applies to policy, law, business, education and health schools.

- Typically these schools want you to be a first rate researcher in your field, and have publication and academic expectations similar to that of a regular department. So in some ways treat this like any other application or interview, and don’t assume that your paper or talk need to speak to a completely different audience.

- That said, professional schools are typically attracted to the study of real world problems, and some fluency in and ties to the real world help. You can indicate this in your cover letter and casually in conversations.

- Assuming the school is an interdisciplinary place, it is typically helpful if you can signal that you appreciate being around people from other disciplines. If you don’t feel this way then a professional school might not be a good fit.

- One benefit of these places is that your students will go on to careers in this field, often very successful ones, and this will give you a natural network if you choose to foster it. If your research is applied and in these areas, this network can become useful over time. It’s also enjoyable to continue to meet and interact with former students over time, something that rarely happens with undergraduates.

- A downside is that these schools typically do not have PhD programs, or the programs are smaller, more specialized, and probably don’t place as many students in good academic jobs as the economics or political science department at the university. This can lighten your advising load but it means fewer research assistants or junior collaborators immediately at hand, and fewer future colleagues to mentor directly. It’s not that hard to overcome these disadvantages, but you should be aware of them.

- When hiring, any school will wonder, “how open is this candidate to coming to a school of [insert profession here]”. If you have any way to relieve that concern, casually doing so can help. This might be a few lines in your cover letter about why that kind of school is a good fit, or showing that you understand and value the advantages.

Here are a few thoughts on specific types of professional schools:

- Public policy schools

- It’s important for your I struggle to come up with more advice than the generic professional school advice, but really these are not such different places to work or apply to than a regular department.

- It’s important that your research engages real world issues but you won’t be expected to be actively involved in policy at most schools, especially as a junior faculty.

- Business schools

- Teaching tends to be especially important (since MBAs pay a lot of money for these degrees), and the schools want to hire excellent communicators who enjoy teaching and are gifted at it. Your job talk should display these skills.

- I’m told that these schools will appreciate case studies, and that if you wanted to focus on this market it wouldn’t be a bad idea to get some experience writing one. That strikes me as an over-specific investment for most people, however.

- If you have a fluency with business, past experience, a social network that includes a lot of business, research partners and clients in business, it does not hurt to mention this. It indicates a better understanding of student needs and a relevance to the general community. This is probably more important as you get outside the handful of elite institutions, who would prioritize your academic contributions.

- Some of the advantages of a business school job: the pay is often higher; you may have lower teaching loads, and teaching that is concentrated in a shorter span of time.

- Some of the disadvantages: you probably will have to teach an MBA topic that is not your core area of work, which is interesting to some people and abhorrent to others; ditto for teaching MBA students; and the publication and tenure expectations can (at some schools) be heterogeneous or hard to discern. Do they value cases? Do they want to see popular recognition of your work? Or do they want you to be a serious normal academic?

- Public health schools

- I don’t understand the public health job market that well. It seems to be less formal, and more relationship based.

- That said, if these schools are looking for someone with economics or political science training,they will probably advertise in the usual places and interview on that schedule.

- The big drawback to most health schools is that, unlike almost all of the other jobs above, they offer “soft money” jobs. This means you will have to raise your own salary through grants, and your ability to raise funds will influence your promotion throughout your career.

- That said, if you do raise your own salary, the teaching and other obligations are probably lighter than at other departments and professional schools. It’s heterogeneous, though, and so difficult to make generalizations.

- You also have to consider that your colleagues will evaluate your work partly according to the standards of their discipline. Early career awards, many shorter papers, large grants, and other things can be more important at health schools than elsewhere.

- I strongly recommend you get in touch with people who have followed your path into public health schools to get their advice. If you don’t know anyone your advisors should.

Policy and other non-academic jobs

I began my professional life in consulting and considered a policy career after my PhD. Many of my friends and colleagues went on to fulfilling careers in policy, from appointments at the World Bank to the White House to various think tanks. I think these are terrific careers, and I still consider one in my future.

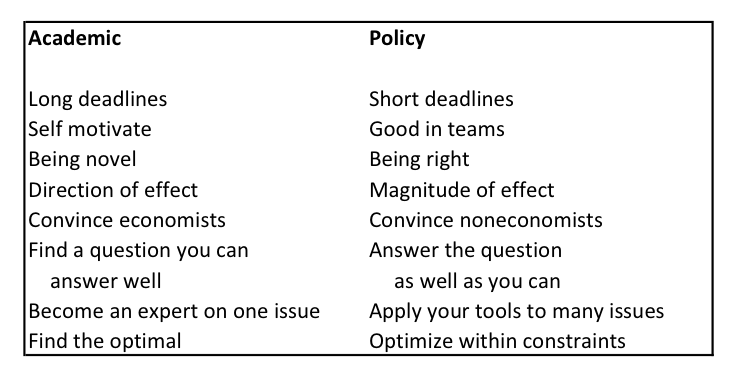

Rachel Glennerster, currently head of J-PAL and a former UK Treasury and IMF official, has some superb advice on her blog. Here is a little table from Rachel, on the big differences between policy and academic jobs:

I don’t have an enormous amount of advice to offer here, and I have not seen much advice collected online, but here are some thoughts:

I don’t have an enormous amount of advice to offer here, and I have not seen much advice collected online, but here are some thoughts:

- If you’re not sure whether you want to be an academic researcher, use your first two summers to work for outside organizations–the World Bank, an investment fund, the Fed, or a think tank. Try each on for size. At the end of your fourth or fifth year of grad school do not make one of the biggest decisions of your life (what kind of job do I want?) with oodles of information about one kind (academia) and zero about the alternatives. You don’t have to be an economist to know that such decision-making is sub-optimal.

- I hate to say it but, if you are undecided about a career in academic research, I don’t recommend you advertise this fact to your advisors and department until you are certain.

- My main rationale: some (but not all) academics will be quick to write you off as ‘not serious’, and should you change your mind later in your PhD you may find that ‘credibility’ difficult to reclaim.

- Certainly you should be candid with your committee about any interest in or openness to non-academic careers. They will have much advice and experience to offer. But don’t declare your intent to follow other paths if you are interested in keeping the academic route open.

-

-

Know something about the institution/organization/firm that is interviewing you. Spend a bit of time on their website so you understand their output, their audience, and their structure.

-

Be able to explain your research in a non-technical way, and be able to offer some implications of your research for policy or for business.

- Be able to demonstrate that you are serious about non-academic jobs. Many non-academic employers will be suspicious of Harvard graduate students and will assume that they are only a back-up if your academic options fall through.

-

Be nice. Be engaging. Non-academic employers are more concerned with personality and style than academic employers because non-academic work is usually more collaborative.

-

- Try to back door to an organization, in addition to the front door.

- Everyone applies through the front door: the junior professional program at [insert development bank here], the advertised position in the federal government. Do that, but also e-mail senior people in the organization directly with a very short introductory note and a CV attached.

- As with academic jobs you increase your offers by increasing the number of applications you make. Except where and how you apply is less clear.

- One strategy: Sit down every day and aim to write just 5 people. After three weeks, that’s 50 e-mails. Forty-four will go unanswered, two will say “thanks, but no vacancy”, two will say “let’s talk”, and two will turn into a job offer.

- Consider some unconventional experiences:

- Work on an election campaign

- Contact ministers or company Presidents in different countries, to see if they need an advisor/analyst

Some online resources to consider:

Other grad school advice

- General grad school advice

- Writing a dissertation. You have to finish this before you graduate, job or no job. Some miscellaneous advice I have found helpful: