The central idea of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), as I understand it, is that, rather than worrying about budget balances, governments and monetary authority should set taxation levels, for a given level of public expenditure, so that the amount of money issued is consistent with low and stable inflation. In this context, the value of the net increase in money issue is referred to as seigniorage. To the extent that seigniorage is consistent with stable inflation, it is achieved by mobilising previously unemployed resources. A crucial question is: what is the scope for seigniorage? In particular (expressing things in MMT terms), is the scope for seigniorage sufficient to permit the introduction of ambitious programs like a Green New Deal without the need for higher taxes to

Topics:

John Quiggin considers the following as important: Tax and public expenditure, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

The central idea of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), as I understand it, is that, rather than worrying about budget balances, governments and monetary authority should set taxation levels, for a given level of public expenditure, so that the amount of money issued is consistent with low and stable inflation. In this context, the value of the net increase in money issue is referred to as seigniorage. To the extent that seigniorage is consistent with stable inflation, it is achieved by mobilising previously unemployed resources.

A crucial question is: what is the scope for seigniorage? In particular (expressing things in MMT terms), is the scope for seigniorage sufficient to permit the introduction of ambitious programs like a Green New Deal without the need for higher taxes to prevent inflation.

The recent episode of Quantitative Expansion in the US provides some evidence here. Contrary to the dire predictions of some critics, QE did not lead to runaway inflation. This is consistent with the view, shared by MMT advocates and mainstream Keynesians, that, in the context of a liquidity trap and zero interest rates, there is substantial scope for monetary expansion.

How much is “substantial”?

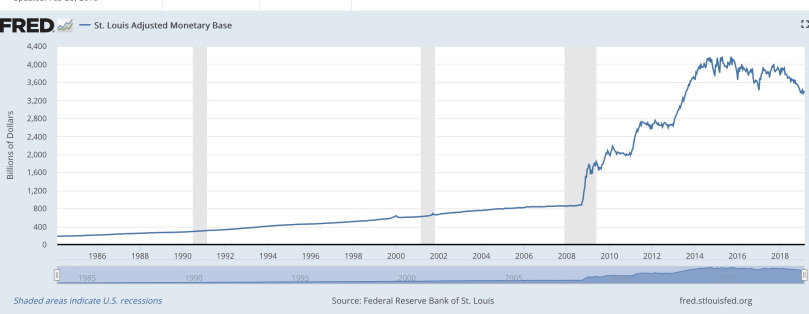

According to the St Louis Fed,

the monetary base grew from around $800 billion to just over $4

trillion between 2008 and 2016. That’s an increase of $3.2 trillion,

which is a lot of money. Expressed in terms of GDP, though, it doesn’t

seem quite as large. Over eight years, $3.2 trillion is $400 billion a

year or around 2 per cent of US GDP ($20 trillion).

Assuming that this is an upper bound for the scope of seigniorage, it’s much smaller than the amount needed to finance, say, a Green New Deal.

What qualifications need to be made here? First, it might be argued that QE should have been more aggressive than it was. Certainly, looking at things with a focus on the real economy, as traditional Keynesians do, the stance of fiscal and monetary policy overall was too restrictive. But, if you assess things on the MMT criterion of low and stable inflation, the Fed got it pretty much right. Deflation was avoided, and the inflation rate was restored to the target level of 2 per cent in a reasonably short time. That’s continued as QE has been partially reversed in recent years.

A second point is that QE wasn’t (directly) an expansionary fiscal policy of the kind Keynesians favour. Rather, the budget deficit (smaller than it should have beeb) was financed with bonds. The sale of these bonds to the public would have depressed demand, but instead the Fed bought them (and also some high-grade corporate bonds). That’s not the best way to stimulate the economy, but from an MMT viewpoint it’s not obvious that it matters (interested to get comments on this).

Overall, the evidence of QE suggests to me that the basic idea of MMT is sound, at least in the context of a llquidity trap. On the other hand, the same episode shows that a widespread interpretation of MMT, that we can greatly expand public expenditure with no corresponding increase in taxation, is both wrong and inconsistent with the core idea of MMT.