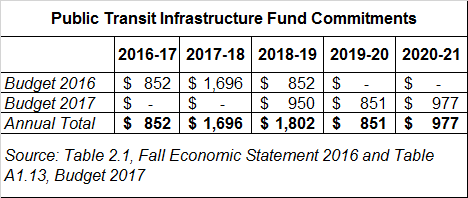

Public transit is a key piece of urban infrastructure, important for getting people where they want to go while limiting congestion and pollution. A central part of the federal government’s infrastructure plan involves expanding and improving public transit, through their newly established Public Transit Infrastructure Fund. Note that Budget 2017 allocates some amount of the total public transit funding to the Canada Infrastructure Bank, the Smart Cities Challenge, and Superclusters (really?), so I have only included the amount committed to the Public Transit bilateral agreements here. This falls short of what the Green Economy Network recommended – we estimated the need to be closer to .76B annually from the federal government (Table 2), which would lead to a reduction of between

Topics:

Angella MacEwen considers the following as important: budgets, federal budget, income tax, public transit

This could be interesting, too:

Nick Falvo writes Homelessness planning during COVID

Nick Falvo writes Report finds insufficient daytime options for people experiencing homelessness

Nick Falvo writes Canada’s 2024 federal budget: What’s in it for rental housing and homelessness?

Angry Bear writes Deficits, Debts, Surpluses, Borrowing, Budgets, etc. Processes

Public transit is a key piece of urban infrastructure, important for getting people where they want to go while limiting congestion and pollution. A central part of the federal government’s infrastructure plan involves expanding and improving public transit, through their newly established Public Transit Infrastructure Fund.

Note that Budget 2017 allocates some amount of the total public transit funding to the Canada Infrastructure Bank, the Smart Cities Challenge, and Superclusters (really?), so I have only included the amount committed to the Public Transit bilateral agreements here.

This falls short of what the Green Economy Network recommended – we estimated the need to be closer to $1.76B annually from the federal government (Table 2), which would lead to a reduction of between 11-20 Mt of GHGs annually, but we are talking about committing serious funding to transit, which is good.

The language around the investment in public transit focuses on reducing congestion, lowering GHGs, and shortening commute times, all issues that the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) identified in their transit campaign. What isn’t mentioned though, is affordability.

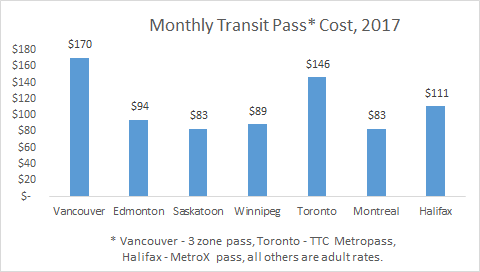

And the cost of a monthly transit pass is, frankly, too. darn. high.

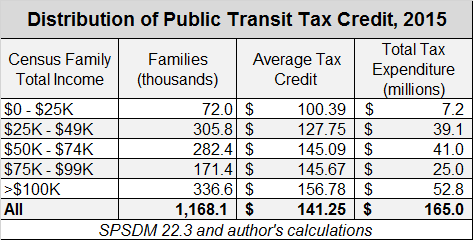

Which is why commuters across Canada were not pleased when Budget 2017 eliminated the (non-refundable) tax credit which allowed users to claim monthly transit passes. While the tax credit wasn’t perfect, it did do something to defray the cost of transit for about 1.7 million transit users.

The justification given by the federal government for getting rid of the tax credit is that it mostly benefited higher income families, and had no measurable impact on increasing ridership. Since it is a non-refundable tax credit (you don’t get anything if you don’t have taxable income), it likely didn’t benefit low income families much. But it is for public transit, so one would guess it benefits the middle of the spectrum, rather than high income folks.

The tax credit could be shared between spouses and their children under 19, so the relevant unit of analysis here is a census family.

You can see that higher income families get a higher average return from the tax credit, and that about a third of families benefiting from the credit have household incomes over $100K. But interestingly, about half of the total tax expenditure is for families with a total annual income below $75,000, and half is for families with incomes above that amount. Median total income in 2014 was $78,870, so that’s a pretty fair distribution for a non-refundable tax credit.

On top of this, there were other tax credits with more skewed distributional benefits that were left untouched. No wonder Toronto and Vancouver transit users are crying foul.

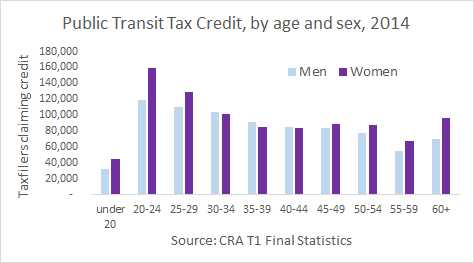

How about a gender lens? According to CRA T1 Final Statistics for the 2014 tax year, women made up about half of the taxfilers claiming the public transit credit. What’s interesting is the age distribution – slightly more men in core working age groups claim the credit, but both older and younger women outnumber men in their age groups.

With all of that in mind, what kind of policies would a social democrat like myself suggest?

First, I would recommend that some amount of the infrastructure funding be tied to affordability. Some provinces and / or municipalities have subsidized passes, but the current system is failing many low income transit users, and getting out of range for even median income folks.

Secondly, if I were going to eliminate the tax credit entirely, I would at least wait until Phase 1 of the transit infrastructure plan was complete. Removing the subsidy from riders before the spending has had a chance to show improvements to the system could hurt ridership and revenues during this rebuilding phase.

If I wanted to keep the tax credit, I would modify it so that it is refundable, individual, and phased out at higher incomes (say, anything over the median income).

Finally, I would look at ways that we’ve prioritized cars in our cities. Policies such as congestion pricing could raise revenues to support public transit, and provide an added incentive for car users to switch to transit.

This is a great example of how policy design needs to keep distributional impacts in mind, so that we’re not further hurting low income families as we’re racing to meet our commitments on climate change.

Enjoy and share: