Chapter 17 of volume 1 of Capital is called “Changes of Magnitude in the Price of Labour-Power and in Surplus Value” and discusses how capitalists extract surplus value in relation to wages.Marx divides the chapter into four sections: (1) Length of the Working Day and Intensity of Labour Constant. Productiveness of Labour Variable.(2) Working-Day Constant. Productiveness of Labour Constant. Intensity of Labour Variable.(3) Productiveness and Intensity of Labour Constant. Length of the Working-Day Variable.(4) Simultaneous Variations in the Duration, Productiveness, and Intensity of Labour. For Marx, the value of labour-power is the value of the maintenance and reproduction of labour, a type of subsistence wage. There can, however, be some variance in the cost of reproducing labour (Marx 1990: 655). Another point is that, for Marx, surplus value takes various forms such as profit, interest and ground rent (Marx 1990: 660).Marx states this theory clearly: “The value of labour-power is determined by the value of the necessaries of life habitually required by the average labourer. The quantity of these necessaries is known at any given epoch of a given society, and can therefore be treated as a constant magnitude. What changes, is the value of this quantity. There are, besides, two other factors that enter into the determination of the value of labour-power.

Topics:

Lord Keynes considers the following as important: Capital, Chapter 17, Critical Summary, Marx, Volume 1

This could be interesting, too:

Michael Hudson writes Beyond Surface Economics: The Case for Structural Reform

Bill Haskell writes Der Gefesselte Marx

Sandwichman writes Ambivalence

Sandwichman writes Book proposal: Marx’s Fetters and the Realm of Freedom: a remedial reading. The Revolutionary Class

Marx divides the chapter into four sections:

For Marx, the value of labour-power is the value of the maintenance and reproduction of labour, a type of subsistence wage. There can, however, be some variance in the cost of reproducing labour (Marx 1990: 655). Another point is that, for Marx, surplus value takes various forms such as profit, interest and ground rent (Marx 1990: 660).(1) Length of the Working Day and Intensity of Labour Constant. Productiveness of Labour Variable.

(2) Working-Day Constant. Productiveness of Labour Constant. Intensity of Labour Variable.

(3) Productiveness and Intensity of Labour Constant. Length of the Working-Day Variable.

(4) Simultaneous Variations in the Duration, Productiveness, and Intensity of Labour.

Marx states this theory clearly:

So (1) the cost of reproducing certain skilled types of adult labour is greater than that for reproducing unskilled labour and (2) the value of labour-power is different for adults and children, and therefore the subsistence wage can vary between different workers because of this. But Marx ignores the latter variables in this chapter.“The value of labour-power is determined by the value of the necessaries of life habitually required by the average labourer. The quantity of these necessaries is known at any given epoch of a given society, and can therefore be treated as a constant magnitude. What changes, is the value of this quantity. There are, besides, two other factors that enter into the determination of the value of labour-power. One, the expenses of developing that power, which expenses vary with the mode of production; the other, its natural diversity, the difference between the labour-power of men and women, of children and adults. The employment of these different sorts of labour-power, an employment which is, in its turn, made necessary by the mode of production, makes a great difference in the cost of maintaining the family of the labourer, and in the value of the labour-power of the adult male. Both these factors, however, are excluded in the following investigation.” (Marx 1906: 568–569).

Instead, Marx’s assumptions are that

In such a scenario,“(1) that commodities are sold at their value; (2) that the price of labour-power rises occasionally above its value, but never sinks below it” (Marx 1906: 569).

So capitalism sees changes in the magnitude of surplus value by these different factors.“… we have seen that the relative magnitudes of surplus-value and of price of labour-power are determined by three circumstances; (1) the length of the working day, or the extensive magnitude of labour; (2) the normal intensity of labour, its intensive magnitude, whereby a given quantity of labour is expended in a given time; (3) the productiveness of labour, whereby the same quantum of labour yields, in a given time, a greater or less quantum of product, dependent on the degree of development in the conditions of production. Very different combinations are clearly possible, according as one of the three factors is constant and two variable, or two constant and one variable, or lastly, all three simultaneously variable. And the number of these combinations is augmented by the fact that, when these factors simultaneously vary, the amount and direction of their respective variations may differ.” (Marx 1906: 569).

To sum up how surplus value is extracted, we can list the three methods:

But of course the three factors might sometimes change at the same time. Marx reviews the various scenarios.(1) by increasing the length of the working day while holding down the real wage to a subsistence level and using the same intensity of labour (that is, increasing absolute surplus value);

(2) decreasing the price of the basic commodities making up the value of the maintenance and reproduction of labour (through use of machines and greater productivity), which reduces the value of the real subsistence wage when the working day and the intensity of labour are held constant (that is, increasing relative surplus value);

(3) given a stable working day, increasing the intensity and speed of work by labourers (often by using machines to speed up work) and so increasing the socially necessary labour time worked per hour, while holding down the real wage to a subsistence level (that is, increasing relative surplus value).

(1) Length of the Working Day and Intensity of Labour Constant. Productiveness of Labour Variable.

Marx sets out three laws under these conditions:

We must remember that there is an absolutely fundamental assumption underlying all these laws: that commodities tend to exchange at their true labour values. Marx has told us that this is his assumption at the beginning of the chapter: “that commodities are sold at their value” (Marx 1906: 569). Without this assumption, as we will see below, the whole analysis falls apart.(1) “A working day of given length always creates the same amount of value, no matter how the productiveness of labour, and, with it, the mass of the product, and the price of each single commodity produced, may vary” (Marx 1906: 569–570). This means that when productivity increases while the length of the working day and intensity of labour are constant, the output per hour rises, but the total amount of labour value produced in one day remains the same, and it is simply divided between more units of the same output product (and this requires that the unit price falls).

(2) “Surplus-value and the value of labour-power vary in opposite directions. A variation in the productiveness of labour, its increase or diminution, causes a variation in the opposite direction in the value of labour-power, and in the same direction in surplus-value” (Marx 1906: 570).

(3) “Increase or diminution in surplus-value is always consequent on, and never the cause of, the corresponding diminution or increase in the value of labour-power” (Marx 1906: 571–572).

The second law means that “no change can take place in the absolute magnitude, either of the surplus-value, or of the value of labour-power, without a simultaneous change in their relative magnitudes, i.e., relatively to each other. It is impossible for them to rise or fall simultaneously” (Marx 1906: 570). Furthermore, when production involves the means of subsistence, “[i]t follows from this, that an increase in the productiveness of labour causes a fall in the value of labour-power and a consequent rise in surplus-value, while, on the other hand, a decrease in such productiveness causes a rise in the value of labour-power, and a fall in surplus-value” (Marx 1906: 571).

The third law concerns the magnitude of surplus value or labour-power, or as Marx says “[a]ccording to the third law, a change in the magnitude of surplus-value, presupposes a movement in the value of labour-power, which movement is brought about by a variation in the productiveness of labour. The limit of this change is given by the altered value of labour-power” (Marx 1906: 572).

The third law is affected by the struggles between workers and capitalists, and so when the value of the subsistence wage falls, the money wage may not always fall all the way to its new level (Marx 1906: 569). That is, the real wage may temporarily rise above subsistence level.

Marx’s final example of the third law is interesting:

Here production of output doubles per hour (and hence per day) with the same total value spread out over more units, but the unit price of the output commodity falls by half (in accordance with the halving of its embodied social necessary labour per unit). Marx seems to think that the commodity produced is a subsistence good, so that even though the money wage of 3 shillings is unchanged it buys twice as much of that good. So here the real wage or value of the labour-power in this industry has risen above subsistence level, even though the rate of exploitation is the same.“The value of labour-power is determined by the value of a given quantity of necessaries. It is the value and not the mass of these necessaries that varies with the productiveness of labour. It is, however, possible that, owing to an increase of productiveness, both the labourer, and the capitalist may simultaneously be able to appropriate a greater quantity of these necessaries, without any change in the price of labour-power or in surplus-value. If the value of labour-power be 3 shillings, and the necessary labour-time amount to 6 hours, if the surplus-value likewise be 3 shillings, and the surplus-labour 6 hours, then if the productiveness of labour were doubled without altering the ratio of necessary labour to surplus-labour, there would be no change of magnitude in surplus-value and price of labour-power. The only result would be that each of them would represent twice as many use-values as before; these use-values being twice as cheap as before. Although labour-power would be unchanged in price, it would be above its value. If, however, the prices of labour-power had fallen, not to 1s. 6d., the lowest possible point consistent with its new value, but to 2s. 10d. or 2s. 6d., still this lower price would represent an increased mass of necessaries. In this way it is possible with an increasing productiveness of labour, for the price of labour-power to keep on falling, and yet this fall to be accompanied by a constant growth in the mass of the labourer’s means of subsistence. But even in such case, the fall in the value of labour-power would cause a corresponding rise of surplus-value, and thus the abyss between the labourer’s position and that of the capitalist would keep widening.” (Marx 1906: 573).

In his second example, the money wage falls towards the true subsistence wage, but remains slightly or somewhat above it. Here it is possible for the real wage to rise even though the money wage would tend to fall as subsistence commodities are cheapened. As Marx says:

But Marx doesn’t say how prevalent such a phenomenon is. And, moreover, if it were really the case that a constantly increasing real wage were a feature of real world capitalism, Marx’s theory would fall apart, because the real wage would not tend to subsistence wages.“In this way it is possible with an increasing productiveness of labour, for the price of labour-power to keep on falling, and yet this fall to be accompanied by a constant growth in the mass of the labourer’s means of subsistence. But even in such case, the fall in the value of labour-power would cause a corresponding rise of surplus-value, and thus the abyss between the labourer’s position and that of the capitalist would keep widening.” (Marx 1906: 573).

To understand Marx’s second scenario properly, let us examine it in depth, because there is a profound problem with Marx’s analysis.

So, in scenario 2 involving time 1 and time 2 with different productivity of labour, we assume the following conditions:

In time 1 (T1), the rate of surplus value s/v (with variables measured in money terms) is 3/3 = 1 or 100%.(1) total working day = 12 hours;

(2) same intensity of labour in both periods of time;

(3) value of labour-power in time 1 (T1) = 3 shillings (or abbreviated as 3s.), and necessary labour-time is 6 hours;

(4) surplus-value in T1 = 3 shillings (or 3s.), and surplus labour-time is 6 hours.

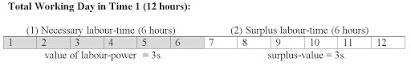

We can represent the working day and the various quantities in the table below:

Each hour of the day in the table is marked from 1 to 12. Here the value of labour-power is equal to 6 hours, and has a value of 3 shillings (or 36 pence). This represents the necessary labour-time equal to the subsistence wage. We can see that with a total labour value of 6 shillings, if the workers were paid the full value of their labour, then they would be paid 6 shillings, or 6 pence per hour.

But if productivity doubled per hour with the same intensity of labour and constant working day, and the business was producing the subsistence good, what would happen?

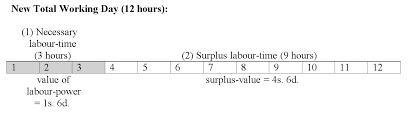

The value of the subsistence wage of labour-power would fall to 1 shilling 6 pence (or 18 pence), because the total amount the workers can produce per hour has doubled. So now necessary labour-time has fallen to 3 hours.

We can represent the working day in this case and the various quantities in the table below:

The rate of surplus value s/v (measured in labour time) is 9/3 or 3, which is 300%. The money wage has fallen but the subsistence wage is the same as measured in the quantity of subsistence goods. The workers are no better off in terms of the real wage.

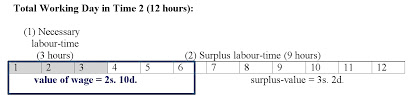

But now let us come to time 2 in Marx’s example where the money wage is 2 shillings 10 pence (34 pence). While the true subsistence wage would be 1 shilling 6 pence, the actual wage is above this.

We can represent time 2 in the table below:

Since the value of the new wage is now 2 shillings 10 pence (or 34 pence), the workers are now being paid for 5 hours and 39.6 minutes of their labour-time: they are being paid over and above their new necessary labour-time of 3 hours (and the value of labour-power is normally the value of that necessary labour-time or subsistence wage, which in this case should be 1 shilling 6 pence).

The blue box with the value of the wage measures the number of hours for which the workers are being paid: as we can see, this is above the necessary labour-time (represented by the first three boxes in grey shading).

So there is clearly a sense in which the workers are being less exploited because

If the original output per hour was 1 subsistence good, the original real wage was 6 subsistence goods. With doubled output per hour, the new real wage in goods is about 11 goods and 1 third of a good.(1) the real value of their wage is above subsistence level: their real wage has risen and

(2) they are being paid for some of their surplus labour time as compared with time 1 where they were being paid for none of it.

But there is a paradoxical result: if we calculate the rate of surplus value, it has risen against time 1. So s/v (measured in values in pence) is 38 pence/34 pence = 1.117 or 111.7%. The original rate of surplus value was 100%.

So, fundamentally, there are serious problems with Marx’s whole concept of surplus value: even as workers can be less exploited in the sense in which their real wage is rising and they are being paid for more than their necessary labour time and some of their surplus labour time as against an earlier period, the Marxist rate of exploitation based on the rate of surplus value can rise in some instances.

But, as I pointed out above, Marx does not inform us how prevalent he thinks such a phenomenon is. This is actually a profoundly devastating point: for if such a phenomenon was very common and prevalent, then workers would be seeing their real wage rise and rise over time and their living standards soar, and they would not feel exploited because, as Marx himself admits, nobody really is interested in the concept of surplus labour time. With a real wage that does not tend towards the subsistence level but can keep rising over time, Marx’s theory falls apart.

And, of course, there are ridiculous and unrealistic assumptions in Marx’s whole theory as follows:

Even Marx abandoned assumption 1 in volume 3 of Capital.(1) that commodities tend to exchange at their true labour values, and

(2) the real wage tends towards the value of the maintenance and reproduction of labour, the subsistence level.

And once we throw aside both these assumptions, we can see that, generally speaking, in the long run in capitalism the workers are liable to be less exploited in two senses:

But to return to Marx’s analysis in Chapter 17.(1) they tend to earn a rising real wage over time above subsistence level, as more and more of their subsistence goods are cheapened along with other goods, and they tend to be paid more and more of their surplus labour time, and

(2) the rate of exploitation falls as the rate of surplus value falls, since real wages rise and commodity prices do not tend to equal labour values, and so the laws of this chapter fall apart.

Marx charges Ricardo with certain errors (Marx 1990: 660), and Marx notes that since the profit rate requires the value of constant capital to be added, the rate of surplus value and rate of profit can diverge (Marx 1990: 660).

Marx ends this section with a comment that raises the transformation problem:

This is a reference to the Classical theory of the tendency of capitalism to converge to an average uniform rate of profit.“It is, besides, obvious that the rate of profit may depend on circumstances that in no way affect the rate of surplus-value. I shall show in Book III. that, with a given rate of surplus-value, we may have any number of rates of profit, and that various rates of surplus-value may, under given conditions, express themselves in a single rate of profit.” (Marx 1906: 574).

(2) Working-Day Constant. Productiveness of Labour Constant. Intensity of Labour Variable

Under these conditions, the total socially necessary labour time performed in a given time is increased to increase the quantity of output, but the unit price of the output product remains the same as the unit value embodied remains the same (Marx 1990: 661).

Marx states:

So here as the intensity of labour per hours in a given fixed working day rises, it is likely that the value of the subsistence wage must rise given the increased labour of the worker.“Hence the length of the working-day being constant, a day's labour of increased intensity will be incorporated in an increased value, and, the value of money remaining unchanged, in more money. The value created varies with the extent to which the intensity of labour deviates from its normal intensity in the society. A given working-day, therefore, no longer creates a constant, but a variable value; in a day of 12 hours of ordinary intensity, the value created is, say 6 shillings, but with increased intensity, the value created may be 7, 8, or more shillings. It is clear that, if the value created by a day's labour increases from, say, 6 to 8 shillings, then the two parts into which this value is divided, viz., price of labour-power and surplus-value, may both of them increase simultaneously, and either equally or unequally. They may both simultaneously increase from 3 shillings to 4. Here, the rise in the price of labour-power does not necessarily imply that the price has risen above the value of labour-power. On the contrary, the rise in price may be accompanied by a fall in value. This occurs whenever the rise in the price of labour-power does not compensate for its increased wear and tear.

We know that, with transitory exceptions, a change in the productiveness of labour does not cause any change in the value of labour-power, nor consequently in the magnitude of surplus-value, unless the products of the industries affected are articles habitually consumed by the laborers. In the present case this condition no longer applies. For when the variation is either in the duration or in the intensity of labour, there is always a corresponding change in the magnitude of the value created, independently of the nature of the article in which that value is embodied.” (Marx 1906: 575).

The average intensity of labour in a given working day might also vary between nations (Marx 1990: 661–662):

(3) Productiveness and Intensity of Labour Constant. Length of the Working-Day Variable“If the intensity of labour were to increase simultaneously and equally in every branch of industry, then the new and higher degree of intensity would become the normal degree for the society, and would therefore cease to be taken account of. But still, even then, the intensity of labour would be different in different countries, and would modify the international application of the law of value. The more intense working day of one nation would be represented by a greater sum of money than would the less intense day of another nation.” (Marx 1906: 575–576).

The total working day may be shortened or lengthened, and Marx identifies three laws as follows:

If the working day is shortened, this reduces the surplus labour and surplus value (Marx 1990: 663).“(1) The working-day creates a greater or less amount of value in proportion to its length—thus, a variable and not a constant quantity of value.

(2) Every change in the relation between the magnitudes of surplus value and of the value of labour-power arises from a change in the absolute magnitude of the surplus-labour, and consequently of the surplus-value.

(3) The absolute value of labour-power can change only in consequence of the reaction exercised by the prolongation of surplus-value upon the wear and tear of labour-power. Every change in this absolute value is therefore the effect, but never the cause, of a change in the magnitude of surplus-value.” (Marx 1906: 576).

If the working day is lengthened, this increases the surplus labour and hence surplus value (Marx 1990: 663).

Although the price of labour-power might rise in such a situation, given the increased energy and more hours of labour expended each day, the daily value of labour-power will rise, and likely the price of labour will drop below its actual value:

This is why there arose limits to the length of the working day.“When the working-day is prolonged, the price of labour-power may fall below its value, although that price be nominally unchanged or even rise. The value of a day's labour-power, is, as will be remembered, estimated from its normal average duration, or from the normal duration of life among the labourers, and from corresponding normal transformations of organised bodily matter into motion, in conformity with the nature of man. Up to a certain point the increased wear and tear of labour-power, inseparable from a lengthened working-day, may be compensated by higher wages. But beyond this point the wear and tear increases in geometrical progression, and every condition suitable for the normal reproduction and functioning of labour-power is suppressed. The price of labour-power and the degree of its exploitation cease to be commensurable quantities.” (Marx 1906: 577–578).

(4) Simultaneous Variations in the Duration, Productiveness, and Intensity of Labour.

Here there are many different combinations but Marx limits himself to two instances.

(4.a) Diminishing Productiveness of Labour with a Simultaneous Lengthening of the Working-Day.

If the price of those commodities which determine the value of labour-power rise, then that value rises, and this requires a rise in necessary labour time per day. But this might be compensated by an increase in the length of the working day so that surplus value can be maintained:

Marx makes an interesting point about the pessimism of Classical economists on the basis of the Napoleonic wars:“Therefore, with diminishing productiveness of labour and a simultaneous lengthening of the working-day, the absolute magnitude of surplus-value may continue unaltered, at the same time that its relative magnitude diminishes; its relative magnitude may continue unchanged, at the same time that its absolute magnitude increases; and, provided the lengthening of the day be sufficient, both may increase.” (Marx 1906: 579).

Marx argues that both intensity of labour and prolongation of the working-day increased in the 1799 to 1815 period, so that surplus value increased.“In the period between 1799 and 1815 the increasing price of provisions led in England to a nominal rise in wages, although the real wages, expressed in the necessaries of life, fell. From this fact West and Ricardo drew the conclusion, that the diminution in the productiveness of agricultural labour had brought about a fall in the rate of surplus-value, and they made this assumption of a fact that existed only in their imaginations, the starting-point of important investigations into the relative magnitudes of wages, profits, and rent.” (Marx 1906: 579).

(4.b) Increasing Intensity and Productiveness of Labour with Simultaneous Shortening of the Working-Day

This process reduces the necessary labour time of the working day.

Marx ends with an interesting analysis:

BIBLIOGRAPHY“If the whole working-day were to shrink to the length of this portion, surplus-labour would vanish, a consummation utterly impossible under the regime of capital. Only by suppressing the capitalist form of production could the length of the working-day be reduced to the necessary labour-time. But, even in that case, the latter would extend its limits. On the one hand, because the notion of ‘means of subsistence’ would considerably expand, and the labourer would lay claim to an altogether different standard of life. On the other hand, because a part of what is now surplus-labour, would then count as necessary labour; I mean the labour of forming a fund for reserve and accumulation.

The more the productiveness of labour increases, the more can the working-day be shortened; and the more the working-day is shortened, the more can the intensity of labour increase. From a social point of view, the productiveness increases in the same ratio as the economy of labour, which, in its turn, includes not only economy of the means of production, but also the avoidance of all useless labour. The capitalist mode of production, while on the one hand, enforcing economy in each individual business, on the other hand, begets, by its anarchical system of competition, the most outrageous squandering of labour-power and of the social means of production, not to mention the creation of a vast number of employments, at present indispensable, but in themselves superfluous.

The intensity and productiveness of labour being given, the time which society is bound to devote to material production is shorter, and as a consequence, the time at its disposal for the free development, intellectual and social, of the individual is greater, in proportion as the work is more and more evenly divided among all the able-bodied members of society, and as a particular class is more and more deprived of the power to shift the natural burden of labour from its own shoulders to those of another layer of society. In this direction, the shortening of the working-day finds at last a limit in the generalisation of labour. In capitalist society spare time is acquired for one class by converting the whole life-time of the masses into labour-time.” (Marx 1906: 581).

Brewer, Anthony. 1984. A Guide to Marx’s Capital. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Harvey, David. 2010. A Companion to Marx’s Capital. Verso, London and New York.

Marx, Karl. 1906. Capital. A Critique of Political Economy (vol. 1; rev. trans. by Ernest Untermann from 4th German edn.). The Modern Library, New York.

Marx, Karl. 1990. Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. Volume One (trans. Ben Fowkes). Penguin Books, London.