Stavros Mavroudeas February 2019 The end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019 were marked by near-widespread volatility in all the major stock markets, as well as by pessimistic forecasts from almost all major Western economic centers. For example, the Wall Street Journal predicts ‘less growth and more uncertainty’, while the IMF and the World Bank cut their forecasts for the growth rate of the global economy. It seems that the big international economic centers are still fearing the ridicule they received in 2008, when they were predicting robust growth exactly before the outbreak of the crisis. But there are also serious substantive reasons for these concerns. As regards stock markets, the significant decline – and the subsequent steep but limited recovery – began in the US (see

Topics:

Stavros Mavroudeas considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Stavros Mavroudeas

February 2019

The end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019 were marked by near-widespread volatility in all the major stock markets, as well as by pessimistic forecasts from almost all major Western economic centers. For example, the Wall Street Journal predicts ‘less growth and more uncertainty’, while the IMF and the World Bank cut their forecasts for the growth rate of the global economy. It seems that the big international economic centers are still fearing the ridicule they received in 2008, when they were predicting robust growth exactly before the outbreak of the crisis. But there are also serious substantive reasons for these concerns.

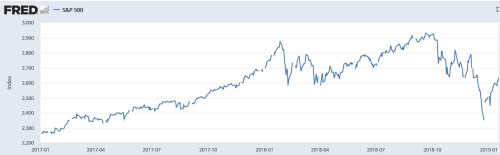

As regards stock markets, the significant decline – and the subsequent steep but limited recovery – began in the US (see Chart 1) and then expanded to other markets because due to the contemporary internationalization of capital the economic cycles of the major economies are now closely interconnected. The significant fall in the US stock market was caused by the conflict between the Trump administration and the Congress regarding the financing of the wall that the former wants to build on the border with Mexico. The United States, since the era of neoliberal rule, have set a limit on its fiscal deficit. The intention of the Trump’s administration to build a wall on the border with Mexico violates this limit. From this stems the controversy with the (Democrat-controlled) Congress. In such controversies, the administration imposes a partial stoppage of the US government, as this is the way the president is trying to coerce the Congress. The expected outcome is a compromise that, in the present case, is slow to materialize due to the intense internal conflicts of the American bourgeoisie.

DIAGRAM 1: S & P 500 Index, Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

But behind these pretexts lay much deeper causes for this turbulence.

Firstly, the conflict within the American bourgeoisie between its ‘globalizing’ and ‘protectionist’ fractions is constantly aggravating and makes the US economic policy extremely contradictory and unstable. Indicatively, the central bank (FED) is following a monetary contraction course (gradually increasing interest rates), while Trump appears to prefer a less rigorous monetary policy. Indeed, the latter even attacked the FED’s President (who is incidentally his choice). This unstable US economic policy, due to its dominant imperialist position, has a decisive impact on the world economy.

Secondly, the promotion of a ‘protectionist’ strategy by the Trump administration and its generalised aggression towards both ‘allies’ and competitors, intensifies the intra-imperialist conflicts. The transition from a ‘globalized’ international economic order to a more fragmented and ethnocentric one is not painless economically. Replacing existing mechanisms and relationships with others can bring future benefits to some of the powerful imperialists, but in the short term it causes a decrease in economic activity.

Third, similar to American, intensifying intra-bourgeoisie conflicts are present in almost all major Western economies. Characteristically, the British bourgeoisie is bitterly divided on Brexit. Also, in the European Union – even in its core countries – there are increasing the conflicts within the bourgeoisie regarding the course and even the very existence of the European imperialist integration project. These internal conflicts reflect the exhaustion of the potential of ‘globalization’ as a counteracting factor to the falling profit rate and denote the quest for alternative counteracting mechanisms. They also express the dispute of hitherto imperialist alliances and blocs and the attempt to change them.

But behind both intensifying intra-bourgeois and intra-imperialist struggles, there is another deeper and more structural cause of concern that feeds them. The 2008 global capitalist crisis has been hidden under the carpet rather than resolved. This crisis was born out of the capital’s falling profitability and took a financial form of expression. The previous global capitalist crisis (1973-4) was caused by the downward trend in the rate of profit and the resulting over-accumulation of capital. The next decades of capitalist restructurings have increased labor exploitation (surplus-value) but failed to drastically reduce capital over-accumulation; thus, the recovery of the profitability was insufficient and unsustainable. That is why the system resorted to a ‘doping» of the accumulation of capital through the expansion of fictitious capital. But this ‘economic dope’ has short legs as it is an insecure bet on future surplus-value. Indeed, this bet has gradually become less realistic (as it required an unrealistic increase in the upcoming surplus-value) resulting in the outbreak of the 2008 global crisis. With the outbreak of the crisis, the system abandoned its pure neo-liberal dogmas and applied its new Orthodoxy, the New Macroeconomic Consensus (which is a fusion of elements of mild neoliberalism and mild Keynesianism). The new recipe – applied at different degrees and times in the main poles of the global capitalist economy – included the relaxation of both fiscal and monetary policy. Afterwards, especially in the EU, financial austerity was restored. At the same time, while the over-accumulation of capital (and the leverage, i.e. the expansion of fictitious capital and debt) was slightly reduced and the labour exploitation increased, the capital depreciation required for the viable return on profitability did not take place. Very soon the system – to varying degrees in each of its major international poles – resorted again to the expansion of fictitious capital. So, today we witness the contradictory phenomenon of both debt and stock market growth.

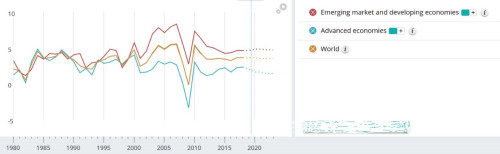

At the same time, however, another important differentiation took place. As can be seen from Chart 2, both before and after the crisis the emerging economies (headed by the BRICs) have acted as a safe haven for multinational companies, as they have had lower capital accumulation (and hence higher profitability and rate of accumulation). Thus, Western multinationals shifted significant parts of their activities (and capitals) and, thus, supplemented their (falling) profitability.

DIAGRAM 2: Growth rates glob. economy, developed and emerging & developing economies, Source: IMF

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

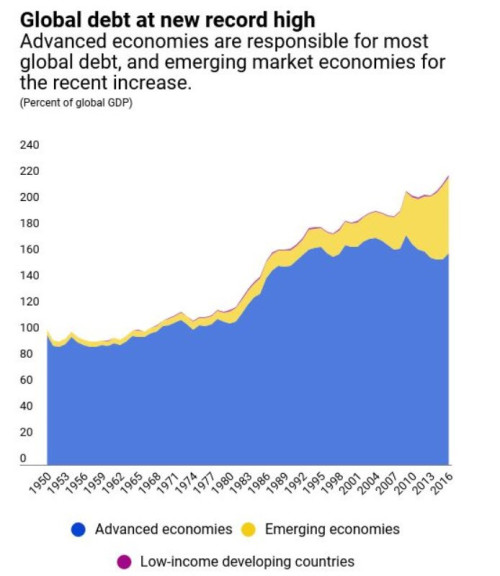

This feature now seems to be changing. On the one hand, declining profitability and over-accumulation of capital appear to be touching emerging economies as well. On the other hand, Western multinationals in particular are redirecting their activity back to their national centers. After all, the Trump policy is pushing such an orientation. Indicatively, emerging economies are increasingly marred by capital flight and currency crises. Similarly, as shown in Chart 3, fictitious capital (with all the problems that they accompanied it) has expanded critically in these countries.

DIAGRAM 3: Debt to GDP ratio, Source: IMF

https://blogs.imf.org/2018/04/18/bringing-down-high-debt/

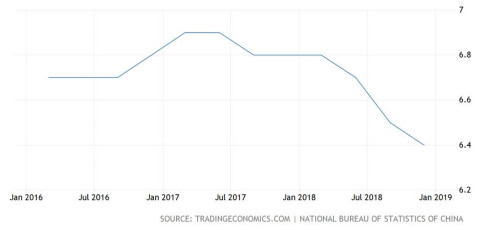

The case of China is indicative, despite the particular characteristics of Chinese state capitalism which significantly differentiate its mode of operation comparing to Western capitalism. China was the main engine to buttress the global capitalist economy during the 2008 crisis. Today, this locomotive is out of breath, as shown in Figure 4.

DIAGRAM 4: China Growth Rate, Source: Trading Economics & National Bureau of Statistics of China

Concluding, the prospects of global capitalism for 2019 are all but auspicious, and the likelihood of another global capitalist crisis (as even official centers are muttering) is growing.