Partager cet article A few weeks ago, the IMF published a study challenging some of the inequality-generating mechanisms described in my book Capital in the Twenty-First Century (see the IMF study here). To make it clear, I am very pleased that my book has made a contribution to stimulating public discussion about inequality, and all the contributions to this debate are worth taking on board! In this instance however, the IMF study does seem to me to be rather weak and not very convincing, and I would like to briefly explain why here. To be precise, I had already replied to similar arguments in my book (which unfortunately is very long!), as well as in several shorter and more recent articles (see for example this one, this one or even this one; other texts are available here). But it is only normal that the discussion should continue, particularly when it concerns questions which are as complex and also as controversial. Briefly, the IMF study aims to demonstrate that there is no systematic relationship between inequality on one hand and the r-g gap separating the return on capital r and the economy’s rate of growth, g, on the other.

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

Partager cet article

A few weeks ago, the IMF published a study challenging some of the inequality-generating mechanisms described in my book Capital in the Twenty-First Century (see the IMF study here).

To make it clear, I am very pleased that my book has made a contribution to stimulating public discussion about inequality, and all the contributions to this debate are worth taking on board!

In this instance however, the IMF study does seem to me to be rather weak and not very convincing, and I would like to briefly explain why here. To be precise, I had already replied to similar arguments in my book (which unfortunately is very long!), as well as in several shorter and more recent articles (see for example this one, this one or even this one; other texts are available here). But it is only normal that the discussion should continue, particularly when it concerns questions which are as complex and also as controversial.

Briefly, the IMF study aims to demonstrate that there is no systematic relationship between inequality on one hand and the r-g gap separating the return on capital r and the economy’s rate of growth, g, on the other. To this end, the study uses a measure of inequality for a number of developed countries between 1980 and 2012, a measure of the r – g gap for these same countries and these same years and attempts to estimate whether there is a statistical relationship between these two variables. Technically, they run a statistical regression between a measure of the inequality and a measure of r – g. The idea of undertaking a regression of this type is not unreasonable as such – on condition however that adequate data is available. Now the problem is that for both terms of the regression the IMF uses totally inappropriate data, both for inequality and for the r – g gap, with the result that it is almost impossible to learn anything useful from this exercise.

Let’s begin with the measurement of inequality. The first problem is that the IMF uses a measurement of inequality of income and not of inequality of wealth. This poses a major difficulty in so far as inequality of income is determined mainly by income from labour (that is to say, the wages of salaried employees and incomes of self- employed persons, which represent the vast majority of incomes, far above dividends, interest, rents and other incomes from capital; the exact labor vs capital shares vary over time and country, but typically amounts to 70% vs 30% for the countries and periods considered by the IMF). Now the range of employment incomes depends on all sorts of mechanisms influencing the working of the labour market (inequality in access to education and skills, technical change and international competition, evolution of the role of trade unions and of the minimum wage, corporate governance and rules for determining the salaries of managers, etc.), and is in no way dependent on the r – g gap (which only applies to the dynamics of the income from capital and its distribution).

As I analyse in my book (see in particular chapters 7-9), as well as in the articles referred to above, the explanation for the rise in inequality of income in a great many countries since the 1980s, in particular the United States, is due in the first instance to mechanisms affecting the labour market and the inequality of labour incomes. There are legitimate disagreements about the respective weight of these various mechanisms in enabling us to account for the rise in inequality of labour incomes. For example, I insist on the role of institutional and political differences between countries (in particular in matters of inequality of access to education, the minimum wage, the salaries of managers and how they are influenced by progressivity of the tax system; on this, see this article with Emmanuel Saez and Stefanie Stantcheva). Others insist more on the role of technical change and international competition (which I do not deny but which does not enable us to explain why inequality has increased much more sharply in the United States and in the United Kingdom than in Germany, Sweden, France or in Japan). In any event these various mechanisms have absolutely nothing to do with the gap between the return on capital, r, and the rate of growth, g. In these circumstances, doing a regression analysis between a general measurement of income inequality (which therefore depends primarily on inequality of income from employment) and the r – g gap makes little sense.

It would have been more justified to use a measure of inequality of wealth. This would have made it possible to estimate the dynamic multiplier effect on the dispersion of wealth of a bigger r – g gap, all things being equal (in particular the saving rates of the various income groups), and for a given level of labour income inequality. In fact, as I demonstrate in my book (see in particular, chapters 10 – 12), the historical data available on wealth shows that it is necessary to use a multiplier mechanism of this sort to explain the very high level of concentration of wealth observed historically in all countries, particularly in the 19th century and until World War One. Unfortunately at the moment this data only exists for a small number of countries over the long-term (France, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Sweden). This is too few to carry out a regression of the type favoured by the IMF. But this is the best we have at this stage, and it shows the importance of this amplifier mechanism. Intuitively, a higher return on capital (and not chiselled off by taxation, inflation or destruction, as was the case in the 19th century and until 1914) and a lower growth rate lead to multiplying and prolonging the inequalities in wealth constituted in the past (for a given level of inequality in employment; see this article for models and simulations). The French individual inheritance data which we have retrieved with Gilles Postel-Vinay and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal in the property registers archives from the time of the French Revolution to the present-day also confirms the importance of this mechanism in accounting for the historical evolution of the wealth distribution and the age-wealth profile by age (see in particular this article and that article). All this in no way means that the r – g mechanism is the only factor responsible: the history of inequality is complex and multidimensional, and research is ongoing. But at the very least this indicates that the multiplier mechanism of inequality in wealth is part of the issue to be considered, provided that we take the time to examine appropriate data.

In fact, to further our research, we have to continue our work on the collection of data on income and wealth, carefully distinguishing between mechanisms which apply on one hand to inequality in employment, in qualifications and in wage formation and on the other, inequality in capital, in accession to property and to the returns on wealth. These two series of mechanisms are linked but bring into play specific approaches. It is precisely this long-term endeavour which we have undertaken in the context of the « World Wealth and Income Database » (WID, http://www.wid.world) a database which my colleagues (Facundo Alvaredo, Tony Atkinson, Emmanuel Saez, Gabriel Zucman) and I have been assembling for the past fifteen years. Today this project brings together over 90 researchers from almost 70 countries all over the world. From this point of view, one of the most beneficial effects of the discussions following the publication of Capital in the Twenty-First Century (which is to a large extent based on this database) is that we now have access to the fiscal and financial archives of a large number of countries, in particular in Asia, Africa and Latin America, which we could not previously use. We are gradually putting on-line the totality of the new data produced, with all the technical details concerning their construction, and a new web site providing more accessible visualisation tools will be available in the coming months.

Instead of heading into poorly constructed statistical regressions and the defence of outdated ideological positions, the IMF economists would do better to spend more time participating in the collective endeavour towards financial transparency and the collection of improved data on inequality.

The second problem posed by the IMF study, at least as serious as the first, is the way in which the gap between r and g is measured. To estimate the return on capital, r, the IMF uses measurements of interest rate on the sovereign debt. The difficulty here is that the large portfolios and high amounts of wealth are not invested in treasury bills (contrary to what the IMF seems to imagine). As I demonstrate in my book (see in particular, Chapter 12), it is impossible to account for the expansion in the biggest fortunes at world level over recent decades if one does not take into account the fact that different levels of wealth have access to very different returns. In other words, the holder of a little Livret A (savings bank pass book) and the owner of a considerable portfolio invested in shares and financial derivatives do not have access to the same capital return, or r. If one chooses to totally ignore this fact, then this makes it difficult to identify the impact on the returns on capital of the dynamics of inequality in wealth.

In fact, if we examine the data available on global rankings of fortunes (data which are very far from perfect, but which do give a more realistic image of the top levels of the distribution than the data from official surveys based on self-declaration), we observe that the highest levels of wealth have risen at a rate of around 6-7% per year in the world since the 1980s, as compared with 2.1% for the average wealth and 1.4% for average income.

This evolution is itself the product of multiple and complex phenomena. The new technological fortunes and the innovators have certainly played their role, as have done the waves of privatisation of natural resources (the Russian millionaires did not invent the oil or natural gas reserves: they simply became their owners and then diversified their portfolio) and of former public monopolies (for example in telecommunications, often sold at low prices to happy beneficiaries, like Carlos Slim in Mexico, as in many other countries). We also observe that above a certain level of fortune, wealth tends to grow mechanically at a higher rhythm than the average.

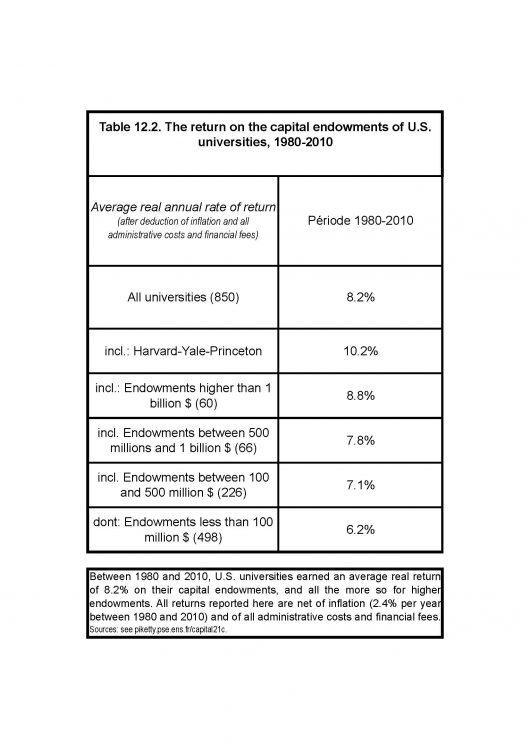

This is confirmed by the examination of the data available on the returns obtained by the financial endowments of the major American universities (data which at least have the merit of being made public, which is not the case for individual portfolios). We observe extremely high returns (an average of 8.2% per annum between 1980 and 2010, after deduction of inflation and all the administrative costs) with a high graduation depending on the size of the endowment (6% for the smallest endowments to over 10% for the bigger ones):

In other words, the capital endowments of American universities have not been placed in Treasury bills for quite some time: the detailed data available to us shows that on the contrary these very high returns are obtained by investments in extremely risky and sophisticated assets (commodity and equity derivatives, unquoted companies, etc.) which are not accessible to small portfolios. Unfortunately we do not have such detailed data for individual portfolios, but everything leads us to believe that this same type of effect is in play (not perhaps to the same extent). In any event, it does not seem to me to be very serious to claim to be studying the unequal impact of the r – g gap on the dynamics of wealth by simply ignoring this inequality of returns obtained by the various investors and by attributing to each the interest rate of the sovereign debt.

One last point: I would like to make it clear that this type of controversy seems to me to be perfectly natural and healthy for democratic debate. Some would prefer that the ‘experts’ in economic questions come to an agreement to enable the rest of the world to draw the necessary conclusions. I quite understand this standpoint and at the same time it seems to me unrealistic. Research in the social sciences, of which economics is an integral part, whatever some may think, is and always will be hesitant and imperfect. It is not designed to produce readymade certainties. There is no universal law of economics: there is only a multiplicity of historical experiences and imperfect data, which we have to examine patiently to endeavour to draw some provisional and uncertain lessons. Everyone must gain an understanding of these questions and of these materials to draw their own conclusions without allowing themselves to be intimidated by the well-argued opinions of others.