Is the crisis in Catalonia due to over-centralization and the intransigeance of the authorities in Madrid? Or is it instead due to generalized competition between regions and countries rivalling with each other, each pursuing their own interests, a process which has already gone much too far both in Spain and in Europe? Let’s take a step backwards. To explain the tougher pro-independence stand, reference is often made to the decision by the Spanish constitutional tribunal in 2010 to invalidate the new status of autonomy for Catalonia, following the high number of actions lodged by the elected members of the Popular Party. Even if some of the measures challenged by the judges did pose serious substantive issues (in particular concerning the regionalisation of justice), the method

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english, Non classé

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

Is the crisis in Catalonia due to over-centralization and the intransigeance of the authorities in Madrid? Or is it instead due to generalized competition between regions and countries rivalling with each other, each pursuing their own interests, a process which has already gone much too far both in Spain and in Europe?

Let’s take a step backwards. To explain the tougher pro-independence stand, reference is often made to the decision by the Spanish constitutional tribunal in 2010 to invalidate the new status of autonomy for Catalonia, following the high number of actions lodged by the elected members of the Popular Party. Even if some of the measures challenged by the judges did pose serious substantive issues (in particular concerning the regionalisation of justice), the method used was indeed very likely to cause offence, in particular as the status had been adopted by the Spanish Parliament in 2006 (which at the time had a socialist majority), as well as by a referendum in Catalonia.

However, one should not forget that the new rules for fiscal decentralisation were effectively validated in 2010, both for Catalonia and for the Spanish regions as a whole. Now these rules, which have been in force since 2011, already make Spain one of the most decentralised countries in the world in budgetary and fiscal matters, including when compared with federal States much larger in size.

In particular, since 2011 the base for income tax is split 50-50 between the federal and the regional governments. In practice, in 2017 the rates of the income tax contribution to the federal budget ranged from 9.5% (for annual taxable incomes below 12,450 euros) to 22.5% (above 60,000 euros). If a region decides to apply these same rates for its part of the income tax base, then the taxpayers in this region will pay in total income tax rates ranging from 19% to 45% and the tax revenue will be shared equally between Madrid and the region. Each region can also decide to set its own income tax bands and its own additional rates, higher or lower than the federal rates. In all cases, the corresponding income accrues to the region which no longer has to share it with other regions (for the list of rates applied in 2017, see here, p.505).

This sort of system poses numerous problems. It challenges the very idea of solidarity within the country and comes down to playing the regions against each other, which is particularly problematic when the issue is one of income tax as this is supposed to enable the reduction of inequalities between the richest and the poorest, over and above regional or professional identities. Since 2011, this system of internal competition has also led to dumping strategies and the fictitious fiscal domiciliation of the wealthiest households and firms which in the long run may risk undermining the progression of the whole (see e.g. this article by D. Agrawal and D. Foremny).

By comparison, in the United States, a country with seven times the population of Spain, and well-known for its attachment to decentralisation and the rights of the individual States, income tax has always been a tax which was almost exclusively federal. In particular, since its creation in 1913 it is the federal income tax which ensures the function of fiscal progressivity with rates applicable to the highest incomes which were set on average at over 80% between 1930 and 1980 and have stabilised a little below 40% since the 1980-1990s. The federal states can vote additional rates but in practice these are very low rates, usually between 5% and 10%. Doubtless, taxpayers in California (the State with a population which is alone almost as big as Spain and six times more numerous than Catalonia) would have been very happy to keep half of the income from the federal tax for themselves and their children; but the fact is that have never succeeded in so doing (if truth be told, they have never really tried).

In the Federal Republic of Germany, an example closer to Spain, income tax is exclusively federal; the Lander do not have the right to vote additional taxes. Nor do they have the right to keep the least part of the revenue for themselves, whatever the taxpayers in Bavaria may think. We would like to make it clear that the rationale for additional tax rates at regional or local level is not necessarily a bad thing as such (in France it could enable the replacement of the local poll tax or taxe d’habitation) on condition that they remain moderate. By choosing to split income tax 50-50 between state and regional governments, Spain has gone too far and now finds itself in a situation where some of the Catalans would like to keep 100% of the revenue from income tax on becoming independent.

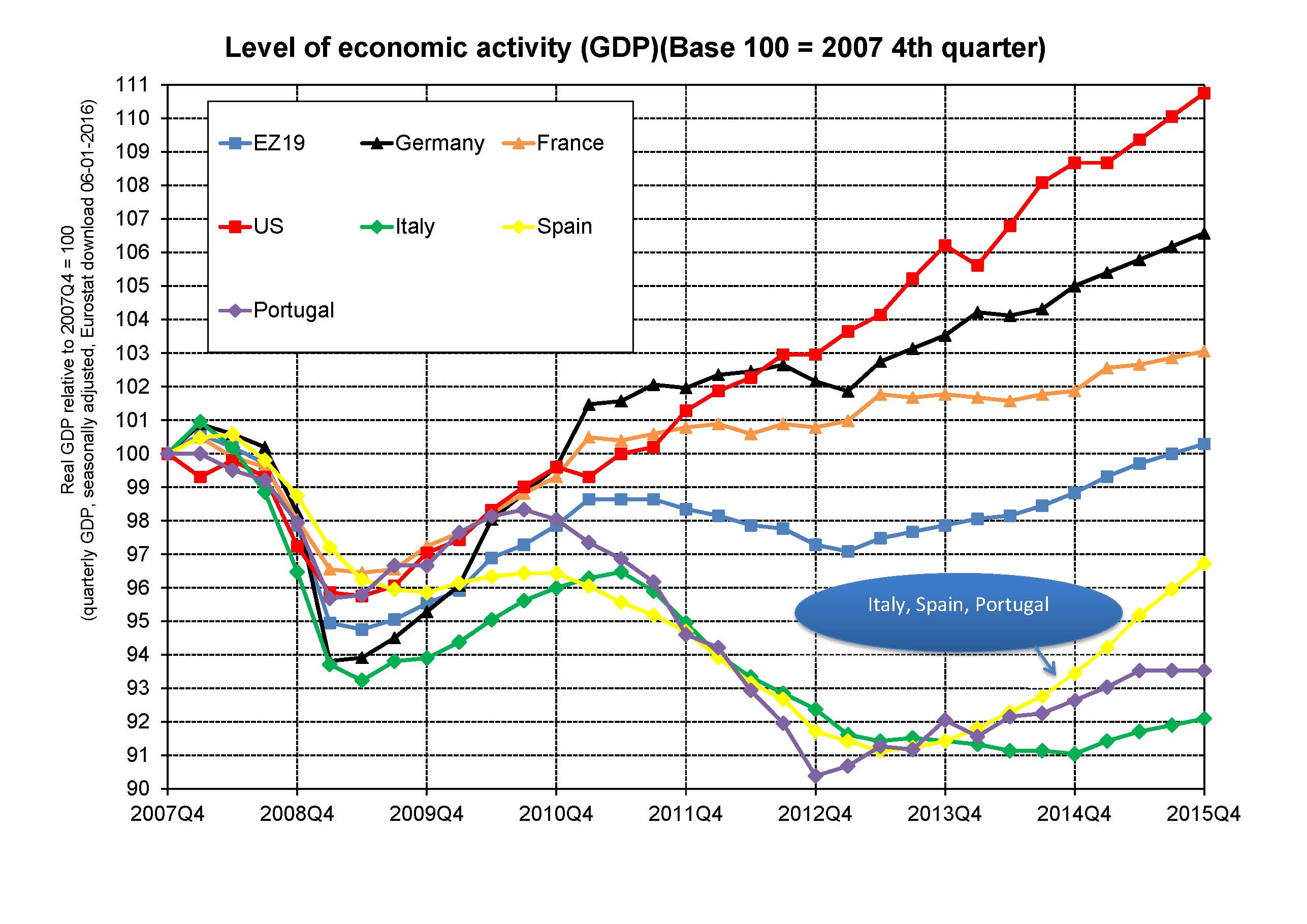

Europe also bears a great deal of responsibility in this crisis. Apart from the catastrophic management of the crisis in the Euro zone, in particular at the expense of Spain, for decades now Europe has been promoting a model of civilisation based on the idea that it is possible to have everything at the same time: integration in a large European and world market, without any real obligation for ensuring fiscal solidarity and the financing of the public good. In these circumstances, why not try one’s luck by making Catalonia a tax haven along the lines of Luxembourg? To be sure, there is a federal European budget but it is very small. Above all, it should logically be based on those who benefit most from economic integration, with a common European tax on corporate profits and the highest incomes, as is the case in the United States (one could also endeavour to do better, but we are far from this). It is only by ensuring that solidarity and fiscal justice are at long last central to its practices that Europe will successfully tackle separatisms.