Next month Karl Marx will be 200 years old. What would he have thought of the sad state Russia is in today? This is a country which never ceased to claim to be ‘Marxist Leninist’ throughout the Soviet period. Doubtless he would have denied any responsibility for a regime which appeared long after his death. Marx grew up in a world of censitory oppression and private property sacralization, where even the owners of slaves could be handsomely compensated if their property was violated (for ‘liberals’ like Toqueville this was a matter of course). It would have been difficult for him to anticipate the success of social democracy and the welfare state in the 20th century. Marx was 30 years old at the time of the 1848 revolutions and he died in 1883, the year of Keynes’ birth. Both were

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english, Non classé

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

Next month Karl Marx will be 200 years old. What would he have thought of the sad state Russia is in today? This is a country which never ceased to claim to be ‘Marxist Leninist’ throughout the Soviet period. Doubtless he would have denied any responsibility for a regime which appeared long after his death. Marx grew up in a world of censitory oppression and private property sacralization, where even the owners of slaves could be handsomely compensated if their property was violated (for ‘liberals’ like Toqueville this was a matter of course). It would have been difficult for him to anticipate the success of social democracy and the welfare state in the 20th century. Marx was 30 years old at the time of the 1848 revolutions and he died in 1883, the year of Keynes’ birth. Both were acute commentators on their times; we were doubtless wrong to take them for consummate theoreticians of the future.

The fact remains that when the Bolsheviks took power in 1917, their action plan were far from being as ‘scientific’ as they claimed. Private property was to be abolished, that was agreed. But how would the relations of production be organised and who would be the new masters? What would be the mechanisms for decision-taking and distribution of wealth in the huge State planning apparatus? For lack of a solution, resort was made to the hyper-personalisation of power and for lack of results, scapegoats were quickly found and imprisoned, with purges being the order of the day. When Stalin died, 4% of the Soviet populations was in prison, more than half for ‘theft of socialist property’ and other petty crimes which helped to improve one’s lot. This is the ‘society of thieves’ described by Juliette Cadiot, and it signs the dramatic failure of a regime which wished to emancipate. To exceed this level of incarceration we have to take the situation of Black American men today (5% of Black adult men are in prison).

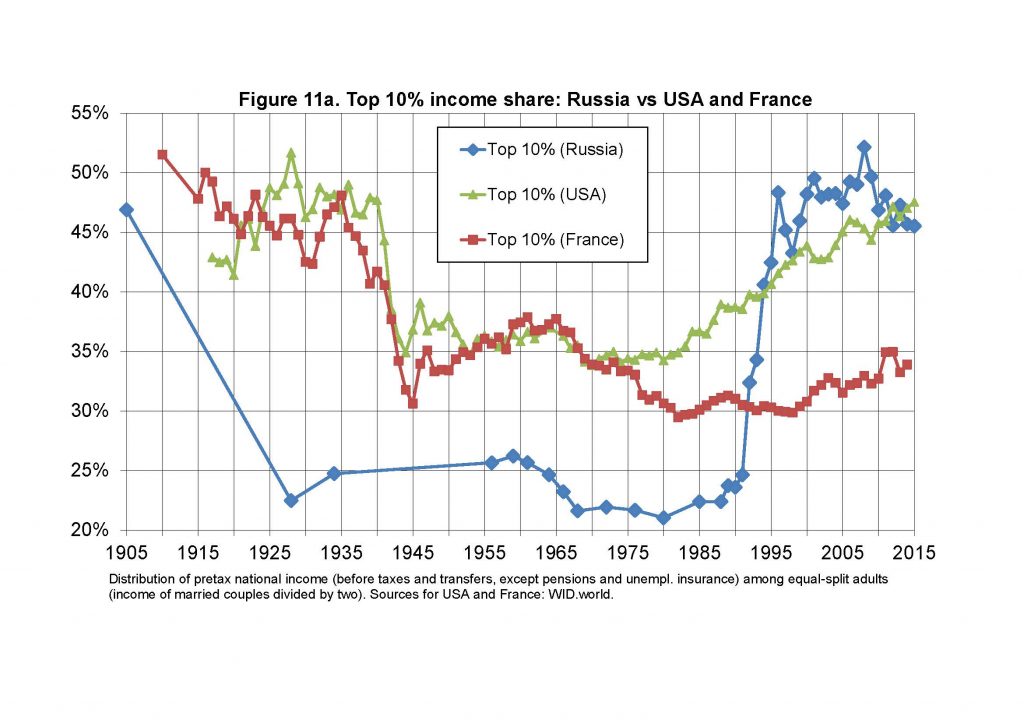

Soviet investments in infrastructures, education and health do indeed enable a certain amount of catching up; per capita national income stagnated before the Revolution at about 30-40% of the level in Western Europe; it rose to over 60% in the 1950s. But the lag increased in the 160s-1970s, life expectancy even began to fall (a unique phenomenon in time of peace), the regime was on the brink of implosion. The dismantling of the USSR and its productive apparatus led to a fall in standard of living in 1992-1995. Income per capita rose as from 2000 and in 2018 stands at approximately 70% of the West European level in terms of purchasing power parity (but is twice as low if one uses the prevailing rate of exchange, given the weakness of the rouble). Unfortunately inequalities have risen much more rapidly than the official statistics claim, as is demonstrated in a recent study carried out with Filip Novokmet and Gabriel Zucman (available on WID.world).

More generally, the Soviet disaster led to the abandon of any ambition of redistribution. Since 2001, income tax is 13%, whether your income be 1,000 roubles or 100 billion roubles. Even Reagan and Trump have not gone as far in the destruction of progressive taxation. There is no tax on inheritance in Russia, nor in the People’s Republic of China. If you want to pass on your fortune in peace in Asia, it is better to die in the ex-Communist countries and definitely not in the capitalist countries such as Taiwan, South Korea or Japan where the tax rate on inheritance on the highest estates has just risen from 50% to 55%.

But while China has succeeded in conserving a degree of control on capital outflows and private accumulation, the characteristic of Putin’s Russia is an unbounded drift into kleptocracy. Between 1993 and 2018, Russia had massive trade surpluses: approximately 10% of GDP per annum on average for 25 years, or a total in the rage of 250% of GDP (two and a half years of national production). In principle that should have enabled the accumulation of the equivalent in financial reserves. This is almost the size of the sovereign public fund accumulated by Norway under the watchful gaze of the voters. The official Russian reserves are ten times lower – barely 25% of GDP.

Where has the money gone? According to our estimates, the offshore assets alone held by wealthy Russians exceed one year of GDP, or the equivalent of the entirety of the official financial assets held by Russian households. In other words, the natural wealth of the country, (which, let it be said in passing, would have done better to remain in the ground to limit global warming) has been massively exported abroad to sustain opaque structures enabling a minority to hold huge Russian and international financial assets. These rich Russians live between London, Monaco and Moscow: some have never left Russia and control their country via offshore entities. Numerous intermediaries and Western firms have also recouped large crumbs on the way and continue to do so today in sport and the media (sometimes this is referred to as philanthropy). The extent of the misappropriation of funds has no equal in history.

Rather than apply commercial sanctions, Europe would do better to finally go for these assets and to address Russian public opinion. Today post-Communism has become the worst ally of hyper-capitalism: Marx would have appreciated the irony but this is not a reason for putting up with it.