The biggest election in world history has just begun in India: there are over 900 million electors. It is often said that India learned the art of parliamentary democracy through contact with the British. The observation is not entirely false, provided that we add that India is now implementing this art on an unprecedented scale in a political community of 1.3 billion people, split along huge socio-cultural and linguistic divisions, which is a much more complex issue. Meanwhile the United Kingdom has considerably difficulty in remaining united at the level of the British Isles. Following in the steps of Ireland at the beginning of the 20th century, it may just possibly be Scotland’s turn to leave the United Kingdom and its Parliament at this start of the 21st century. For its part, the

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

The biggest election in world history has just begun in India: there are over 900 million electors. It is often said that India learned the art of parliamentary democracy through contact with the British. The observation is not entirely false, provided that we add that India is now implementing this art on an unprecedented scale in a political community of 1.3 billion people, split along huge socio-cultural and linguistic divisions, which is a much more complex issue.

Meanwhile the United Kingdom has considerably difficulty in remaining united at the level of the British Isles. Following in the steps of Ireland at the beginning of the 20th century, it may just possibly be Scotland’s turn to leave the United Kingdom and its Parliament at this start of the 21st century. For its part, the European Union and its 500 million inhabitants have still not succeeded in setting up democratic rules for the adoption of the slightest common tax and continue to grant a right of veto to Grand Duchies in which barely 0.1% of its citizens reside. Instead of explaining in learned fashion that nothing in this fine system can be changed, European leaders would be well advised to look at the Indian Union and its model of federal and parliamentary Republic.

Obviously not everything in the garden is rosy in the biggest democracy in the world. The country’s development is marred by huge inequalities and poverty which is too slow in declining. One the principle innovations of the electoral campaign which is ending is the proposal made by the party in Congress to introduce a system of basic income, the NYAY (nyuntam aay yojana, minimum guaranteed income). The amount announced is 6,000 rupees per month and per household, or the equivalent of about 250 Euros in purchasing power parity (3 times less at the current exchange rate), which is far from negligible in India (where the median income does not exceed 400 Euros per household). This system would apply to the poorest 20% of Indians. The cost would be significant (a little over 1% of GDP) but not prohibitive.

As always with proposals of this type, it is important not to stop there and not take the basic income as a miracle solution or a final settlement. Setting up a fair distribution of wealth and a model for sustainable and equitable development, requires the backing of a total package of social, educational and fiscal measures, the basic income only being one element therein. As Nitin Bharti and Lucas Chancel have shown, public expenditure on health has stagnated at 1.3% of GDP between 2009-2013 and 2014-2018, and the investment in education even fell from 3.1% to 2.6%. A complex balance remains to be found between the reduction in monetary poverty and these social investments which condition the closing of the gap between India and China. China has found a way to mobilise greater resources to raise the level of training and health of the population as a whole.

The fact remains that the proposal by Congress has the merit of stressing the questions of redistribution and of going beyond mechanisms of ‘quotas’ and ‘reservations’. True, these have enabled a fraction of the lower castes to access the university, public sector jobs and to hold elective offices but they are not sufficient.

The biggest drawback of the proposal is that Congress has chosen to remain very discrete about its financing. This is a pity because it afforded an opportunity to rehabilitate the role of progressive taxation, and to definitely turn the page on its neo-liberal moment in the 1980s and 1990s. Above all it would have provided an occasion for more explicitly coming closer to the new alliance between the socialist parties and the lower castes (SP, BSP) who propose the creation of a federal tax of 2% on net worth over 25 million Rupees (1 million Euros in parity of purchasing power), which would bring in the equivalent of the amounts required for the NYAY, and strengthen the progressivity of the federal income tax.

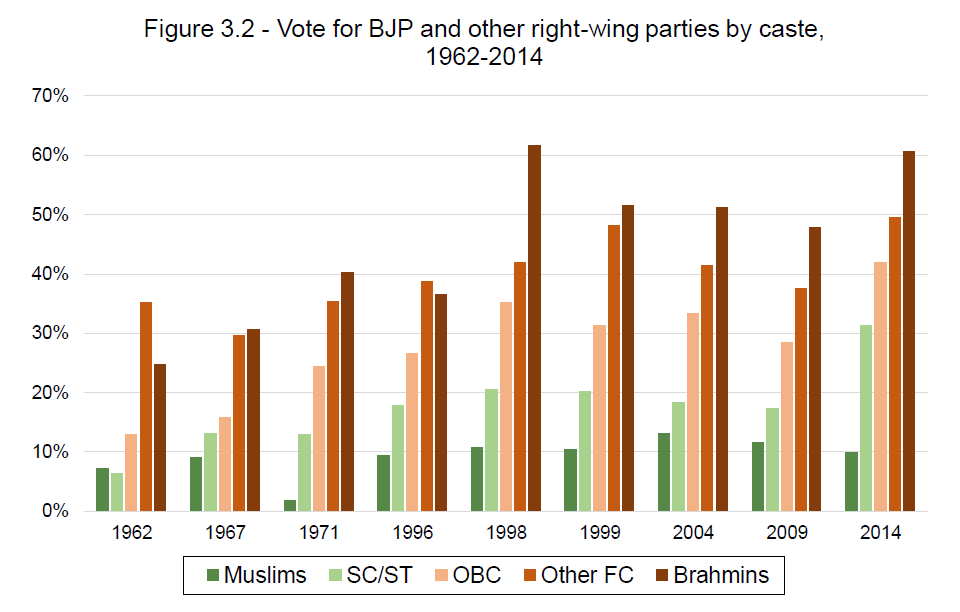

Fundamentally, the real issue at stake in this election is the constitution in India of a left-wing coalition, both egalitarian and multi-cultural, the only coalition capable of beating the pro-business and anti-Muslim nationalism of the BJP. This time this may not be enough. The Congress, which was formerly the hegemonic party from the centre, is still led by the far from popular Rahul Gandhi (from the Nehru-Gandhi family) whereas the BJP had the sense to adopt Modi, for the first time a leader from humble origins. Congress fears it may be outflanked and lose the control of the government if it were to launch into an over-explicit coalition with parties to its left.

Furthermore, Modi is massively funded by Indian big business, in a country which is well-known for its total absence of regulation in this respect. In addition, he has skilfully exploited the attack in Pulwama in Jammu and Kashmir and the air-raids which followed to activate the anti-Pakistan feelings and accuse the Congress and the left-wing parties of collusion with fundamentalist Islam (this does not only happen in France), in what may well remain the turning point in the campaign.

Whatever the case may be, the seeds sown will grow along with the politico-ideological changes ongoing all over the world. The decisions debated in India will increasingly affect us all. In this respect, this Indian election is indeed an election of global importance.

PS: the graph on BJP vote by caste is extracted from this research by Banerjee-Gethin-Piketty on changing political cleavages in India.