Can we restore positive meaning to the idea of internationalism? Yes, but on condition that we turn our backs on the ideology of unfettered free trade which has till now guided globalisation and adopt a new model for development based on explicit principles of economic and climatic justice. This model must be internationalist in its final aims but sovereignist in its practical modalities, in the sense that each country, each political community must be able to determine the conditions for the pursuit of trade with the rest of the world without waiting for the unanimous agreement of its partners. The task will not be simple and it will not always be easy to distinguish this sovereignism with a universalist vocation from nationalist-type sovereignism. It is therefore particularly urgent

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english, Non classé

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

Can we restore positive meaning to the idea of internationalism? Yes, but on condition that we turn our backs on the ideology of unfettered free trade which has till now guided globalisation and adopt a new model for development based on explicit principles of economic and climatic justice. This model must be internationalist in its final aims but sovereignist in its practical modalities, in the sense that each country, each political community must be able to determine the conditions for the pursuit of trade with the rest of the world without waiting for the unanimous agreement of its partners. The task will not be simple and it will not always be easy to distinguish this sovereignism with a universalist vocation from nationalist-type sovereignism. It is therefore particularly urgent to indicate the differences.

Lets us suppose that one country, or a political majority within it, considers it would be desirable to set up a highly progressive tax on top income and wealth holders to bring about a major redistribution in favour of the poorest socioeconomic groups while at the same time financing a programme for social, educational and ecological investment. To move in this direction, this country is considering a taxation at source on corporate profits and most importantly a system of financial registry that would enable the identification of the ultimate owners of the shares and dividends and thus the application of the desired progressive tax rates at individual level. The whole package could be completed by an individual carbon card thus encouraging responsible behaviour, while taxing the highest emissions heavily ; those who benefit from the profits of the most polluting firms would also be taxed. Once again this would demand a knowledge of the owners.

Unfortunately, a financial registry of this type has not been provided for by the Treaties for the free circulation of capital established in the 1980s-1990s, in particular in Europe in the framework of the Single European Act (1986) and the Maastricht Treaty (1992), texts which have strongly influenced those adopted thereafter throughout the world. This ultra-sophisticated legal architecture, still in force today, has de facto created a quasi-sacred right to get rich by using the infrastructures of one country, then by one click on a laptop, transferring one’s assets to another jurisdiction, with no possibility provided for the community to find any trace of it. Following the crisis in 2008, as the excesses of financial deregulation came to light, agreements on the automatic exchange of banking information have been developed within the OECD, true. But these measures, established on a purely voluntary basis, do not contain the slightest sanction for recalcitrant countries.

Let us suppose therefore that a country wishes to accelerate the movement and sets up a redistributive form of taxation and a financial registry. Now, let’s imagine that one of its neighbours does not share this point of view and applies a ridiculously small profit tax and carbon tax on firms based on its territory (whether in actual fact or fictiously), while refusing to transmit the information as to their owners. In these circumstances, the first country should in my view impose commercial sanctions on the second ; the amount would vary, depending on the firm and the extent of the fiscal and climatic damage caused. Recent research has shown that sanctions of this type would bring in substantial revenues and would encourage other countries to co-operate. Of course, we would have to plead that these sanctions are merely correcting unfair competition and the non-respect of the climate agreements. But the latter are so vague and, on the contrary, the treaties on the free circulation of goods and capital are so sophisticated and absolute, particularly at European level, that a country which adopts this approach stands a considerable risk of being condemned by European or International bodies (The Court of Justice of the European Union, the World Trade Organisation). If such were the case, the country should leave the Treaties in question unilaterally, while at the same time suggesting new ones.

What is the difference between the social and ecological sovereignism which I have just outlined and nationalist sovereignism (for example, of the Trump, Chinese, Indian or, tomorrow, the French or European variety) based on the defense of identity of a specific civilisation and of interests deemed to be homogenous within it ?

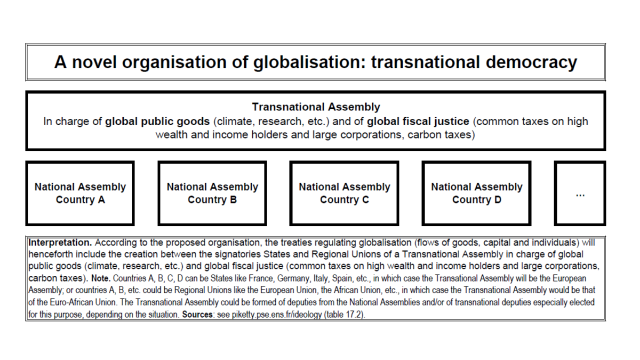

There are two. Firstly, before taking possible unilateral measures, it is crucial to propose to other countries a model for cooperative development based on universal values : social justice, reduction of inequality, conservation of the planet. It is also important to describe in detail the transnational assemblies (such as the French-German Agreement created last year, but with real powers) which ideally would be in charge of global public property and common policies for fiscal and climatic justice.

Then, if these social-federalist proposals are not taken up at the moment, the unilateral approach should nevertheless remain incentive-based and reversible. The aim of sanctions is to encourage other countries to exit from fiscal and climatic dumping ; the aim is not to establish permanent protectionism. From this point of view the sectoral measures with no universal basis such as the GAFA tax should be avoided because they easily lend themselves to ratcheting up sanctions (wine taxes versus digital taxes, etc.)

To claim that this type of path is easy to follow and well sign-posted would be absurd : it all still has to be invented. But historical experience demonstrates that nationalism can only lead to exacerbating inegalitarian and climatic tensions and that there is no future for unfettered free trade. One more reason for thinking, as from today, about the conditions for a new internationalism.

Note. For a first estimate of the possible amount of anti-dumping sanctions, see Ana Seco Justo, « Profit Allocation and Corporate Taxing Rights: Global and Unilateral Perspectives« , PSE 2020.