The Covid crisis is forcing us to rethink the tools of redistribution and solidarity. Proposals are springing up everywhere: basic income, job guarantee, inheritance for all. Let’s say it straight away: these proposals are complementary and not substitutable. In the long run, they must all be implemented, in stages and in this order. Let’s start with basic income. Such a system is dramatically lacking today, especially in the South, where the incomes of the working poor have collapsed and containment rules are unenforceable in the absence of a minimum income. Opposition parties had proposed introducing a basic income in India in the 2019 elections, but the ruling nationalist-conservatives in Delhi are still dragging their feet. In Europe, various forms of minimum income exist in most

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english, Non classé

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

The Covid crisis is forcing us to rethink the tools of redistribution and solidarity. Proposals are springing up everywhere: basic income, job guarantee, inheritance for all. Let’s say it straight away: these proposals are complementary and not substitutable. In the long run, they must all be implemented, in stages and in this order.

Let’s start with basic income. Such a system is dramatically lacking today, especially in the South, where the incomes of the working poor have collapsed and containment rules are unenforceable in the absence of a minimum income. Opposition parties had proposed introducing a basic income in India in the 2019 elections, but the ruling nationalist-conservatives in Delhi are still dragging their feet.

In Europe, various forms of minimum income exist in most countries, but with many shortcomings. In particular, there is an urgent need to extend access to them to younger people and students (this has already long been the case in Denmark), and especially to people without a fixed address or bank account, who often face insurmountable obstacles. It is worth noting in passing the importance of the current discussions on central bank digital currencies, which should ideally lead to the creation of a genuine public banking service, free and accessible to all, the antithesis of the systems dreamt up by private operators (whether decentralised and polluting, like bitcoin, or centralised and inegalitarian, like the projects of Facebook or private banks).

It is also essential to extend the basic income to include low-paid workers, with a system of automatic payment on pay slips and bank accounts, without people having to ask for it, linked to the progressive tax system (also deducted at source).

Basic income is an essential but insufficient tool. In particular, its amount is always extremely modest. Depending on the proposal, it is generally between half and three quarters of the full-time minimum wage, so that, by construction it can only be a partial tool in the fight against inequality. For this reason, it is preferable to speak of a basic income than of a universal income (a notion that promises more than this minimalist reality).

A more ambitious tool that could be implemented as a complement to the basic income is the job guarantee system recently proposed in the framework of the discussions on the Green New Deal (see in particular Pavlina Tcherneva, The Case for a Job Guarantee, 2020). The idea is to offer all those who want it a full-time job at a minimum wage set at a decent level ($15 per hour in the United States). Funding would be provided by the federal government and jobs would be offered by public employment agencies in the public and voluntary sectors (municipalities, communities, non-profit organisations). Placed under the dual patronage of the Economic Bill of Rights proclaimed by Roosevelt in 1944 and the March for Jobs and Freedom organised by Martin Luther King in 1963, such a system could make a powerful contribution to the process of de-commodification and collective redefinition of needs, particularly in the areas of personal services, energy transition and renovation of buildings. It also enables, at a limited cost (1% of GDP in Tcherneva’s proposal), to bring back into employment all those who were deprived of a job during recessions and thus avoid irremediable social damage.

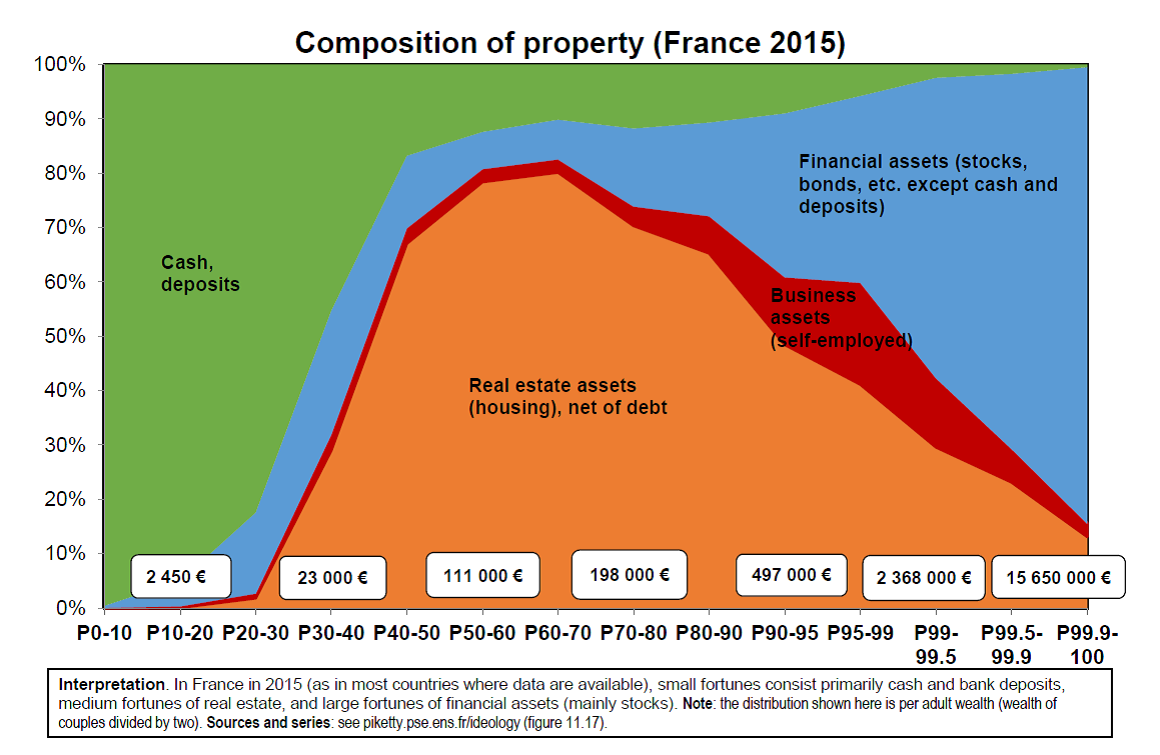

Finally, the last device that could complete the package, in addition to the basic income, the job guarantee and the set of rights associated with the most extensive social state possible (free education and health, highly redistributive pensions and unemployment benefits, trade union rights, etc.), is a system of inheritance for all. When we study inequality in the long term, the most striking thing is the persistence of a hyper-concentration of property. The poorest 50% have hardly ever owned anything: 5% of total wealth in France today, compared to 55% for the richest 10%. The idea that we just have to wait for wealth to spread doesn’t make much sense: if that were the case, we would have seen it long ago.

The simplest solution is a redistribution of inheritance allowing the whole population to receive a minimal inheritance, which, to fix ideas, could be of the order of 120,000 Euros (i.e. 60% of the average wealth per adult). Paid to all at 25 years of age, it would be financed by a mix of progressive wealth and inheritance taxes yielding 5% of national income (a significant amount but one that could be considered in the long term). Those who currently inherit nothing would receive 120,000 euros, while those who inherit a million euros would receive 600,000 Euros after taxation and endowment. We are therefore still far from equality of opportunity, a principle often defended at a theoretical level, but which immediately puts the privileged classes on their guard whenever one envisages a beginning of concrete application. Some will want to put constraints on its use; why not, provided they apply to all inheritances.

Inheritance for all aims to increase the bargaining power of those who have nothing, to enable them to refuse certain jobs, to acquire housing or to embark on a personal project. This freedom is frightening for employers and property owners, as it would make workers less docile, but liberating for all others. We are only just emerging from a long period of enforced confinement. All the more reason to start thinking and hoping again.