What can we learn from the new World Inequality Report 2022 published this week? The result of the contributions from over a hundred researchers from all continents, this Report, published every four years, allows us to examine the major fault lines in the world’s inequalities. Beyond the now well-known findings on the rise of income inequalities over the last few decades, three main new features can be identified, relating to wealth, gender and environmental inequalities. Let us start with wealth. For the first time, thanks to the work of Luis Bauluz, Thomas Blanchet and Clara Martinez-Toledano, researchers have gathered systematic data that allows for a comparison of wealth distributions in all countries of the world, from the bottom of the distribution to the top. The overall

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english, Non classé

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

What can we learn from the new World Inequality Report 2022 published this week? The result of the contributions from over a hundred researchers from all continents, this Report, published every four years, allows us to examine the major fault lines in the world’s inequalities. Beyond the now well-known findings on the rise of income inequalities over the last few decades, three main new features can be identified, relating to wealth, gender and environmental inequalities.

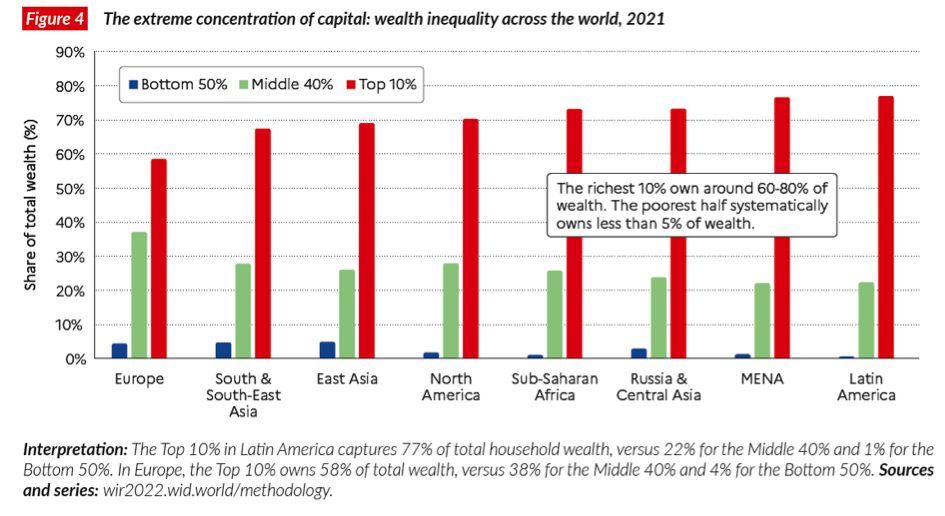

Let us start with wealth. For the first time, thanks to the work of Luis Bauluz, Thomas Blanchet and Clara Martinez-Toledano, researchers have gathered systematic data that allows for a comparison of wealth distributions in all countries of the world, from the bottom of the distribution to the top. The overall conclusion is that wealth hyper-concentration affects all world regions (and it has worsened during the Covid pandemic). At global level, in 2020 the poorest 50% of the world’s population owned just 2% of total private property (real estate, business and financial assets, net of debt), while the richest 10% own 76% of the total.

Latin America and the Middle East have the highest levels of inequality, followed by Russia and sub-Saharan Africa, where the poorest 50% own just 1% of everything there is to own, while the richest 10% own around 80%. The situation is slightly less extreme in Europe, but there is really nothing to be proud of: the poorest 50% own 4% of the total, compared to 58% for the richest 10%.

Faced with this observation, several attitudes are possible. We can wait patiently for growth and market forces to spread the wealth. But given that more than two centuries after the Industrial Revolution the share held by the poorest 50% is barely 4% in Europe and 2% in the United States, we may be waiting a long time. It can also be argued that the current situation is the best we can do, and that any attempt to redistribute wealth would be economically dangerous. The argument is weak. In Europe, the share held by the richest 10% was 80-90% of total wealth until 1914. It has fallen in a century to less than 60% today, mainly to the benefit of the 40% of the population between the top 10% and the bottom 50%. This wealthy middle class was thus able to acquire housing and set up businesses, which greatly contributed to the prosperity of the Trente Glorieuses, (the period from 1945 to 1975 following World War II).

What can be done to prolong this long-term movement towards equality, which is historically inseparable from the evolution towards greater prosperity? Ideally, a redistribution of inheritance should be considered. At the very least, we need to stop promising tax giveaways to the wealthiest and focus on reforming the property tax, which is a very heavy and unfair tax for people on the way to home ownership, and which should become a progressive tax on net wealth.

The second lesson of the World Inequality Report 2022 is gender inequality. Thanks to the data collected by Theresa Neef and Anne-Sophie Robillard, it is now possible to measure the evolution of women’s share of total labour income for all countries in the world. This shows the extent to which gender inequalities remain high: at the global level, in 2020, women received barely 35% of labour income (compared to more than 65% for men). This share was 31% in 1990 and 33% in 2000: we can therefore see that progress exists but is extremely slow. In Europe, the share of women will reach 38% in 2020, which is still very far from parity.

This indicator gives a less watered-down and more accurate view of reality than the explanation for a given job: it shows precisely to what extent women do not have access to the same jobs and working hours as men, particularly as a result of multiple prejudices and discrimination and the lesser efforts made by the public authorities to structure the jobs in which women are most present (in particular in personal care, mass retailing and cleaning jobs). The slow progress observed around the world over the last few decades also reflects the growing share of the wage bill captured by very high earners, who are overwhelmingly male. In some regions, such as China, there has even been a decline in the share of women in total labour income. All this calls for much more proactive measures than those adopted so far.

The third new feature of the 2022 Report is environmental inequalities. Too often, the climate debate is reduced to a comparison of average carbon emissions per country and their evolution over time. Thanks to the work of Lucas Chancel, we now have data on the distribution of emissions within countries and in different regions of the world. We can see that the poorest 50% of the world’s population have relatively reasonable levels of emissions, for example 5 tonnes per capita in Europe. Meanwhile, the average emission reaches 29 tonnes for the top 10%, and 89 tonnes for the richest 1%. The conclusion is obvious: we will not meet the climate challenge by cutting everyone at the same rate. More than ever, the planet will have to take into account the multiple inequalities that cut across it to overcome the social and environmental challenges that undermine it.