ATHENS — The recent elections in France and Britain have confirmed the political establishment’s simultaneous vulnerability and vigor in the face of a nationalist insurgency. This contradiction is the motif of the moment — personified by the new French president, Emmanuel Macron, whose résumé made him a darling of the elites but who rode a wave of anti-establishment enthusiasm to power. A similar paradox is visible in Britain in the surprising electoral success of the Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, in depriving Theresa May’s Conservatives of an outright governing majority — not least because the resulting hung Parliament seemingly gives the establishment some hope of a change in approach from Mrs. May’s

Topics:

Yanis Varoufakis considers the following as important: DiEM25, English, Essays, Op-ed, Politics and Economics, The New York Times

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Waldmann writes Visting www.nytimes.com I am shocked, shocked to find that editing is going on there.

Beverly Mann writes Scrutiny of John Roberts: He Says He Will Vote to Uphold the University of Texas Affirmative Action Admissions Policy Because White Applicants Have Political Power. Seriously.

Chris Blattman writes The United States is not headed for civil war

Chris Blattman writes Is America on brink of civil war? Such predictions are overblown and dangerous.

ATHENS — The recent elections in France and Britain have confirmed the political establishment’s simultaneous vulnerability and vigor in the face of a nationalist insurgency. This contradiction is the motif of the moment — personified by the new French president, Emmanuel Macron, whose résumé made him a darling of the elites but who rode a wave of anti-establishment enthusiasm to power.

ATHENS — The recent elections in France and Britain have confirmed the political establishment’s simultaneous vulnerability and vigor in the face of a nationalist insurgency. This contradiction is the motif of the moment — personified by the new French president, Emmanuel Macron, whose résumé made him a darling of the elites but who rode a wave of anti-establishment enthusiasm to power.

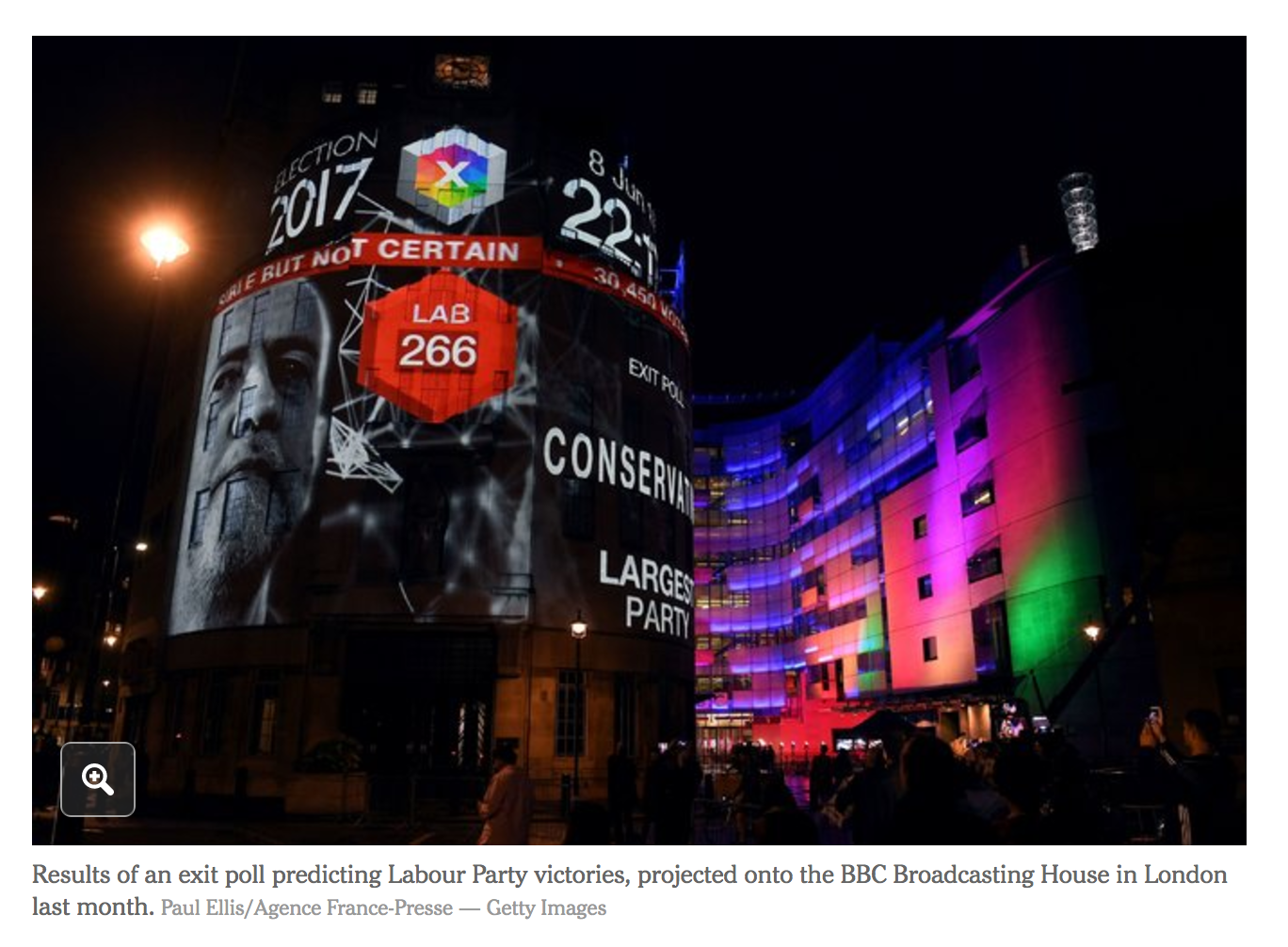

A similar paradox is visible in Britain in the surprising electoral success of the Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, in depriving Theresa May’s Conservatives of an outright governing majority — not least because the resulting hung Parliament seemingly gives the establishment some hope of a change in approach from Mrs. May’s initial recalcitrant stance toward the European Union on the Brexit negotiations that have just begun.

Outsiders are having a field day almost everywhere in the West — not necessarily in a manner that weakens the insiders, but neither also in a way that helps consolidate the insiders’ position. The result is a situation in which the political establishment’s once unassailable authority has died, but before any credible replacement has been born. The cloud of uncertainty and volatility that envelops us today is the product of this gap.

For too long, the political establishment in the West saw no threat on the horizon to its political monopoly. Just as with asset markets, in which price stability begets instability by encouraging excessive risk-taking, so, too, in Western politics the insiders took absurd risks, convinced that outsiders were never a real threat.

One example of the establishment’s recklessness was releasing the financial sector from the restrictions that the New Deal and the postwar Bretton Woods agreement had imposed upon financiers to prevent them from repeating the damage seen with the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. Another was building a system of world trade and credit that depended on the booming United States trade deficit to stabilize global aggregate demand. It is a measure of the sheer hubris of the Western establishment that it portrayed these steps as “riskless.”

When the ensuing financialization of Western economies led to the great financial crisis of 2007-8, leaders on both sides of the Atlantic showed no compunction about practicing welfare socialism for bankers. Meanwhile, more vulnerable citizens were abandoned to the mercy of unfettered markets, which saw them as too expensive to hire at a decent wage and too indebted to court otherwise.

When the insiders’ rescue schemes — including quantitative easing, the buying up of toxic assets, the eurozone’s bailouts and temporary nationalizations of banks — succeeded in refloating banks and asset prices, they also left whole regions in the United States, and whole countries on Europe’s periphery, stagnant. It was not rising inequality that provoked undying anger among these discarded people. It was the loss of dignity, of the dream of social mobility, as well as the experience of living in communities that were leveled down, so that a majority of people were increasingly equal but equally miserable.

As more and more voters became mad as hell, governing parties lost elections between 2008 and 2012 in the United States, Britain, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Greece and elsewhere. The problem was that the incoming administrations were as much part of the establishment as the outgoing ones. And so they made bipartisan the very approach that had caused the wave of anger that carried them into office.

That approach was doomed, not least because economic forces were already working against the new governments. After the 2008 crash, the monetary easing by central bank institutions like the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England fended off a global repeat of the Great Depression. China’s unleashing of a huge credit-fueled construction boom, which saw investment rise to 48 percent of national income in 2010, from 42 percent in 2007, and total credit climb to 220 percent of national income by 2014, from 130 percent in 2007, also softened the financial market failures of the West.

Unsurprisingly, though, these central bank money-creation schemes and the Chinese credit bubble proved unable to prevent severe regional depressions, which struck from Detroit to Athens. Nor could they prevent sharp global deflation from 2012 to 2015.

By 2014, voters had begun to give up on the new administrations they had voted for after 2008 in the false hope that the establishment’s loyal opposition could provide new solutions. Thus, 2015 saw the first challenges to the insiders’ authority start to surface.

In Greece — a small country, yet one that has proved to be a bellwether thanks to its gargantuan and systemically significant debt — protests against the debt bondage imposed on the population evolved into a progressive, internationalist coalition led by the Syriza party that came from nowhere to win government. In Spain, a similar movement, Podemos, began to rise in the polls, threatening to do the same.

In Britain, a left-wing internationalist tendency that had been marginal in the Labour Party coalesced around the leadership campaign of Jeremy Corbyn — and surprised itself by winning. Soon after, the independent socialist senator from Vermont, Bernie Sanders, carried the same spirit into the Democratic Party primaries.

Everywhere, the political establishment treated these left-of-center, progressive internationalists with a mixture of contempt, ridicule, character assassination and brute force — the worst case, of course, being the treatment of the Greek government in which I served during the first half of 2015. Historians may mark that year as when the establishment turned truly illiberal.

By 2016, the establishment’s arrogance met its first, frightful nemesis: Brexit. The shock waves from the insiders’ unheralded defeat in that referendum rippled across the West. They brought new energy to Donald Trump’s outsider campaign in the American presidential election, and they invigorated Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France.

From the West to the East, a new Nationalist International — an allied front of right-wing chauvinist parties and movements — arose.

The clash between the Nationalist International and the establishment was both real and illusory. The venom between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump was genuine, as was the loathing in Britain between the Remain camp and the Leavers. But these combatants are accomplices, as much as foes, creating a feedback loop of mutual reinforcement that defines them and mobilizes their supporters.

The trick is to get outside the closed system of that loop. The progressive internationalism of Mr. Corbyn’s Labour Party, Mr. Sanders’s supporters and the Greek anti-austerity movement came to offer an alternative to the deceptive binaries of establishment insiders and nationalist outsiders. An interesting dynamic ensued: As the insiders defeated or sidelined the progressive internationalist outsiders, it was the nationalist outsiders who benefited. But once Mr. Trump, the Brexiteers and Ms. Le Pen were strengthened, a remarkable new alignment took place, with a series of unstable mergers between outsider forces and the establishment.

In Britain, we saw the Conservative Party, a standard-bearer of the establishment, adopt the pro-Brexit program of the tiny, extreme nationalist U.K. Independence Party. In the United States, the outsider in chief, Mr. Trump, formed an administration made up of Wall Street executives, oil company oligarchs and Washington lobbyists. As for France, the anti-establishment new president, Mr. Macron, is about to embark on an austerity agenda straight out of the insiders’ manual. This will, most probably, end by fueling the current of isolationist nationalism in France.

Where does this prey-predator game between the globalist establishment and the isolationist blood-and-soil nationalists leave us?

The recent elections in Britain and France confirm that both strands are alive and kicking, reinforcing each other, as they tussle, to the detriment of a vast majority of their populations. Both Mrs. May’s and the European Union’s negotiating teams in Brussels are investing their efforts in an inevitable impasse, which each believes will bolster their political authority, even though it will disadvantage the populations on both sides of the English Channel that must live with the consequences.

In the United States, Mr. Trump is pursuing an economic policy that, if it has any effect, will set off a run on Treasury bonds at a time when the Fed is tightening monetary policy. A result will be a panicked administration whose reflex will be to impose austerity measures before the midterm elections. Those policies will further disadvantage precisely the regions and social groups that carried Mr. Trump into the White House.

So, what will it take to end this destructive dynamic of mutual reinforcement by the largely liberal establishment insiders and the regressive nationalist outsiders?

The answer lies in ditching both globalism and isolationism in favor of an authentic internationalism. It lies neither in more deregulation nor in greater Keynesian stimulus, but in finding ways to put to useful purpose the global glut of savings.

This would amount to an International New Deal, borrowing from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s plan the basic idea of mobilizing idle private money for public purposes. But rather than through tax-and-spend programs at the level of national economies, this new New Deal should be administered by a partnership of central banks (like the Fed, the European Central Bank and others) and public investment banks (like the World Bank, Germany’s KfW Development Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and so on). Under the auspices and direction of the Group of 20, the investment banks could issue bonds in a coordinated fashion, which these central banks would be ready to purchase, if necessary.

By this means, the available pool of global savings would provide the funds for major investments in the jobs, the regions, the health and education projects and the green technologies that humanity needs. A further step would be to generate more, better-balanced trade by establishing a new international clearing union, to be run by the International Monetary Fund. The new clearing union would help to rebalance trade and create an International Wealth Fund to fund programs to alleviate poverty, develop human capital and support marginalized communities in the United States, Europe and beyond.

Today’s false feud between globalization and nationalism is undermining the future of humanity, and spreading dread and loathing. It must end. A new internationalist spirit that would build institutions to serve the interests of the many is as pertinent today across the world as Roosevelt’s New Deal was for America in the 1930s.