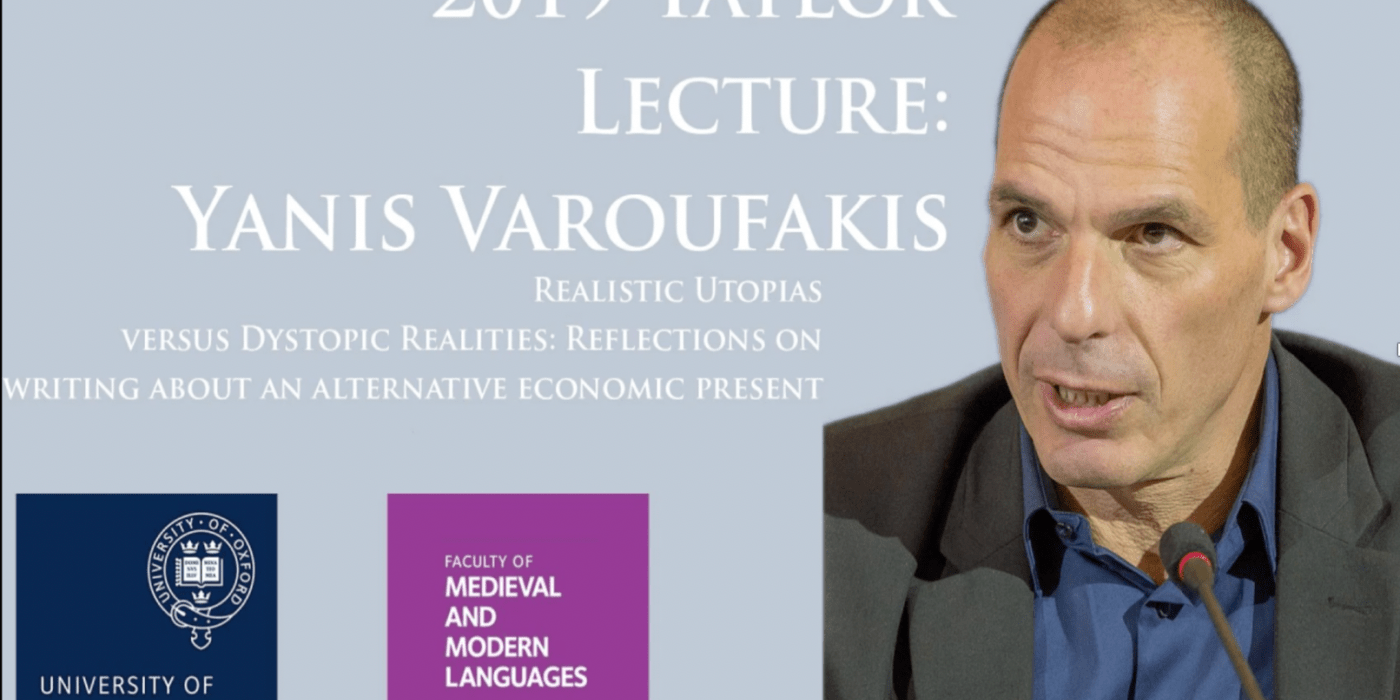

[embedded content] The Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, Oxford University, kindly invited me to deliver the 2019 Taylor Lecture on 12th February 2019. I chose the topic of Realistic Utopias versus Dystopic Realities – my aim being to highlight the manner in which really-existing capitalism is marketed as a utopian science fiction that has nothing to do with… really-existing capitalism. Behind this elegant utopian mathematical the powers-that-be hide a dismal dystopia that is failing humanity in a variety of ways. Plato, King Lear, Coriolanus and the Borg Queen make cameo appearances… For the audio of the lecture, click the photo above. For a video, click. The complete text of the

Topics:

Yanis Varoufakis considers the following as important: Academic, Art and Culture, culture, English, Essays, Talking to my daughter about the economy: A brief history of capitalism, Talks, University

This could be interesting, too:

Chris Blattman writes Top 10 family board games we discovered during the pandemic

Chris Blattman writes Top 10 family board games we discovered during the pandemic

Jeff Mosenkis (IPA) writes IPA’s weekly links

Yanis Varoufakis writes Jamie Galbraith on DiEM-TV’s ‘Another Now’ discussing the “criminal incapacity of the elites”

The Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, Oxford University, kindly invited me to deliver the 2019 Taylor Lecture on 12th February 2019. I chose the topic of Realistic Utopias versus Dystopic Realities – my aim being to highlight the manner in which really-existing capitalism is marketed as a utopian science fiction that has nothing to do with… really-existing capitalism. Behind this elegant utopian mathematical the powers-that-be hide a dismal dystopia that is failing humanity in a variety of ways. Plato, King Lear, Coriolanus and the Borg Queen make cameo appearances…

For the audio of the lecture, click the photo above. For a video, click. The complete text of the talk follows.

12th February 2019, Taylor Lecture, Oxford University

Thank you profusely to all of you for being here tonight and, of course, to the Faculty of Medieval and Foreign Languages for your invitation to deliver the 2019 Taylor Lecture. It is a tremendous honour to be standing in front of your tonight.

To paraphrase Philip K. Dick, reality is that which, when you stop believing it, doesn’t go away. Just like Brexit. We wake up in the morning and, as our dreams or nightmares dissolve into thin air, we realise that, yes, we are indeed living in an unlikely world: Theresa May is still pushing her sad deal. My fellow Greeks continue to live in a decade-long Great Depression. Donald Trump is President of the United States of America!

Now, you may be tempted to think that, Utopia, the theme I chose for tonight, was meant as an escape hatch from from the tyranny of a post-2008 world that begets monsters we thought we had put to rest in 1945 – a life boat to survive our sea of troubles.

I only wish I could treat you to an hour-long flight from the disenchantment of the post-modern 1930s that 2008, our generation’s 1929, triggered off. Alas, utopian thinking, or thinking about utopia, never could offer respite from reality. Like science fiction, all it can do is open up a window from which to catch a glimpse of our reality and see it for the first time, perhaps less painfully, more hopefully.

Utopic thinking has its roots in that first instance when humans looked at each other, noticed the distribution of power in their tribe, and asked: Why this? Why so? It grew in complexity from the earliest of times, with Arcadian myths and parables juxtaposing ideal societies against existing social arrangements. It reached its apotheosis with Plato whose Republic was meant as a party-political manifesto – a piece of sophisticated propaganda by which to turn us into enemies of democracy and enthusiasts for enlightened oligarchy.

More interesting than Plato’s utopian thinking, at least to me, was the use of utopian thinking by playwrights like Aristophanes – thinkers more alert to the dangers implicit in utopian thinking, to the fact that one person’s utopia is another’s nightmare. In Ecclesiazuse, Aristophanes challenges the sanctity of debt and the power of creditors eloquently by making Praxagoras say:

…Tell me, my friend, how the creditor came by the money to lend?

All money, I thought, to the stores had been brought.

I’ve got a suspicion.

I say it with grief, your creditor’s surely a bit of a thief.

Soon after, he has Praxagoras issuing an egalitarian manifest, one that Shakespeare copied and made Gonzalo proclaim centuries later. He declares that behind unsustainable and immoral debt there always lurks illegitimate private ownership. And he dares us to imagine a society in which all good things are equally distributed:

The rule which I dare to enact and declare, is that all shall be equal, and equally share | all the wealth and enjoyments, nor longer endure that one should be rich, and another be poor…

Taking egalitarianism to its logical conclusion, Praxagoras challenges all property-based contracts, including what feminists like Carol Pateman refer to as the sexual contract which underpins all other contracts, private or social.

All women and men will be common and free no marriage or other restraint there will be

Aristophanes’ strategy is subtle but clear: He utilises utopian thinking first to excite, then to appal us. Effectively to warn us, to tell us: Beware what you wish for!

No girl will be permitted to mate except in accord with the rules of the state. By the side of her lover, so handsome and tall, will be stationed the squat, the ungainly, the small. And before she is entitled the beau to obtain, her love she must grant to the awkward and plain

His real message is that the most vengeful of gods is the one who might deliver the society we are foolish enough to think we can design, like megalomaniac architects, in our heads.

In this sense, Aristophanes is closer not just to Thomas More but also, remarkable as it may sound, to both Karl Marx and Karl Popper.

Starting with Thomas More, the slain statesman was indeed much closer to Aristophanes than to Plato. He sketched Utopia as an experiment with an alternative present but also as a cautionary tale of what we will get if we mess with the status quo. This is perhaps why More refused to have Utopia translated from Latin into English – to prevent it from influencing the English masses.

While More’s tale of an egalitarian Arcadia was not terribly original, we owe him a debt of gratitude for his onomatopoeic success, for concocting a terribly useful Greek word, one that means no where, no place – a word that has come to reflect our way of challenging, buttressing and understanding social reality. A word that has spawned three crucial genres:

Eutopias – non-existent but realistic societies described in considerable detail in order to show that a better world is possible – The Republic is an early example; the anti-globalisation movement’s Another World Is Possible a more recent one.

Anti-Utopias – Eutopias gone wrong as a result of the terrible unintended consequences of trying to build an imagined eutopia. The various communities modelled on the thought of Herbert Spencer or, indeed, the Soviet Union being good examples. And,

Dystopias that emerge spontaneously from our existing reality – Brave New World, 1984 and, more recently, Bladerunner, The Matrix, and the Terminator series.

This is perhaps the moment for a personal note. All my life I opposed utopianism as a political or intellectual project, despite having enjoyed hugely literature and movies turning on some utopian or dystopian axis. The reason was my affinity to Aristophanes and my antipathy to Plato.

When I first read Thomas More’s classic, I recoiled just as I had done when reading about the suppression of artists from Plato’s Republic. It was a time when I was learning how to be a socialist that I encountered Karl Marx’s warnings against utopian socialism. And when, a little later, I read Karl Popper’s Open Society and its Enemies, along with 1984, I became convinced of the imminent dangers baked into any blueprint of the good society. To put it bluntly, totalitarianism lurks in the shadows of any grand design that we seek to construct in our heads before implementing it in practice.

Some of you may be baffled by my lumping together of the two Karls, Marx and Popper. Don’t be. I think that, in this, they are on the same page. Popper feared utopian thinking. Marx disdained it. Popper believed that no society can be perfect. Leftwing anarchists, like William Godwin, thought that hell is any group of people. Jean Paul Sartre thought that hell is other people. Marx, in contrast, was more optimistic and allowed himself to think of a society in which he could

… do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, …, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

But Popper and Marx agreed that trying to imagine the perfect society in order to construct it was a bad idea. For Popper, any attempt to construct the perfect society can only go wrong in the sense of erecting some variety of totalitarianism. For Marx, utopian socialists trying to imagine the good society either wasted their time or were unwittingly functional to the reinforcement of the capitalist order. How?

Good, smart people living in slave societies (for example Aristotle) could never imagine a society without slaves – only a society in which, at best, the deserving remained free and the undeserving of freedom lost their freedom but were treated humanely. That’s what convinced Marx that we are unable to exit our current perspective and imagine the good society in a feasible future. If we force ourselves to imagine now how post-capitalism might work, we are bound to end up with a cuddlier version of capitalism, maybe a bucolic higher-tech version of feudalism, a superstitious class-ridden society in which the superflux is, at best, shaken a little more vigorously – to quote King Lear. A vision, in short, that reaffirms capitalism and ignores that only the dispossessed – not us intellectuals in universities like this one – can construct a radically different future.

This is why I never planned to write a book like the one I am currently struggling to write – one firmly lodged in the utopian genre. So, what changed? What made me sidestep a lifelong aversion to utopianism?

Last year I published a little book entitled TALKING TO MY DAUGHTER ABOUT THE ECONOMY, subtitled ‘A brief history of capitalism’. In it, I did what I had been doing for decades, only this time addressing teenagers: Explain to the young how our contemporary world, our political economy, works. The book was well received, even by my political opponents. However, one of them, after praising the book, issued a fair criticism: OK, let’s agree that capitalism sucks, he said (not in these precise words). So does democracy. But what if it is better than any alternative nevertheless?

I must admit that I saw the critic’s point. To answer it I would have to write a whole new book dedicated to answering the question: How could society be better, freer, fairer given our existing technologies and resources? As Popper and Marx understood only too well, this simple sounding question begets a long list of impossible questions: How would the price system work in a post-capitalist society worth fighting for, one that does not degenerate into a Soviet dystopia? Who would run the corporations? The cafeterias? Will there be a stock exchange and if so how would it work? How would we effect the decoupling of prosperity from physical growth to save the planet, while ending private property rights over productive means? What of democratic decision-making? Who would look after the kids and what would sexual politics be like?

As the list of questions grew endlessly in my head, panic began setting in. My natural tendency was to fall back behind Popper’s and Marx’s convenient line namely that: These questions cannot be answered by a mere mortal. And, more importantly, that it is dangerous even to try to answer them.

What stopped me from doing the sensible thing and quit while I was ahead? One thought: The realisation that others are already writing and weaponising utopian texts to underpin misanthropy at a planetary scale. Who are these people? They are the economists whose remarkable economic models have, long ago, become the language, the mathematised theology, in which all the important decisions affecting our lives are couched. They are the financiers who use these economic models to erect science fictions that permit them to create fictitious values that are functional to the most monstrous theft of the commons since the Enclosures. They are the politicians, the experts on your tv screen, the marketing gurus who, based on these utopian models, are shaping every aspect of the dystopic world we live in.

This is why I decided to throw caution to the wind and to write my own utopian text: Because progressives need a realistic utopian vision with which to fight dystopic realities based on unrealistic utopian models. We need working models of how work, production, distribution and exchange can provide shared prosperity without exploitation of either humans or Nature, and without authoritarianism.

To recap, there are unrealistic utopias that have been providing the legitimacy and authority of policies and practices which I would dare call dystopic. These unrealistic utopias will be my theme today. Then there is the need to put forward, as part of a progressive political platform, realistic utopias – sketches of a feasible alternative present that gives hope to the disempowered that TATIANA (the belief ‘That Astonishingly There Is AN Alternative’) can defeat TINA (the dogma that ‘There Is No Alternative’).

So, the book I am working on is divided in two parts. Part Two of the book begins in 2025 when a malfunctioning machine affords my three characters (Eva the neoliberal economist, Iris the radical anthropologist, and Costa the genius Silicon Valley engineer) glimpses of an alternative present – where the same technologies are supporting a society in which social relations are radically different from ours: companies, property rights, money, gender relations.

Part One of the book concentrates on the world that you and I inhabit and, in particular, the unrealistic utopic science-fictions propping up the status quo today. I mention Part One last because it is in on this first part that I shall be speaking about now. Why? First, because I do not want to give the plot of Part Two away. Secondly, because, unlike Part One, I have not written Part Two yet! And, thirdly, because it ought to be a priority is us all to distinguish between (i) reality and (ii) the momentous clash between reality and the utopic, science fiction-like, representations of reality that make it impossible for us to recognise our capitalist reality, let alone criticise or try to overcome it.

Unrealistic utopian foundations of our present dystopia

So, here I go. Let me begin with the best example of what I mean by the unrealistic utopian foundations of really existing capitalism.

Those of you who have suffered a course in standard microeconomics will be able to confirm that mainstream economists model people as fairly unsophisticated robots or fairly sophisticated thermostats. As algorithmic bargain hunters, constantly on the lookout for experiences that satisfy pre-determined desires. Eva, my proxy for the best amongst the mainstream economists, sees people as algorithms that buy stuff, work, laugh and cry as if to maximise the microwatts of private inner glow these activities leave them with. Unable to resist the tiniest net gain in these microwatts, they do what they like and like what they do, within constraints set by the universe – Nature, their budget, the state, other people and, of course, Goddess Luck.

Justice and equality appear as mirages, subjective ‘tastes’ that one may or may not have, similar to a taste for whiskey or Gothic novels. Like colours exist only as illusions in our minds, not in Nature, but red roses or a red flag can motivate us powerfully, so can the mere impression that someone has been ‘wronged’ lure us into drastic deeds. As for gender, Eva’s humans do what they like and like what they do. Every relationship they have is transactional, based on give-and-take. They are incapable of not asking: “What’s in it for me?” And yet, Eva cannot afford to see that her fictional Homo Economicus is an unreconstructed bloke.

She cannot see what a sad bastard her model man is because, if she does, she will forfeit the immense power her utopian fiction affords her. Students used to ask me, when I taught economic theory: Why do economists model humans like bliss-seeking globules oscillating relentlessly under the impulse of stimuli in search of the shortest path to the greatest amount of intertemporal net joy? Why is Eva devoting, in my book, so much energy to a sophisticated model of one-dimensional humans?” Because this particular science fiction allows her to kill two birds with one stone.

Bird No. 1: To identify herself with liberty while stopping anyone from feeling at liberty to tell her what to want

To unshackle freedom fully from paternalism – a worthy cause no doubt – Eva has to separate, to shield, liberty from the society it is practised in. Harriet’s pleasures must be her own and no Tom or Dick should be allowed to tell Harriet that hers are of a lower quality. Eva’s radical move to render sovereign every one of Harriet’s desires is to ban all inter-personal valuations of pleasure – to preserve pleasure as a strictly personal metric of subjective, internal satisfaction. No more prioritising a discontented Einstein over a happy moron, never again celebrating Sylvia Plath over Kim Kardashian.

The happy moron and Kim Kardashian can rejoice, freed from the condescension of our hypocritical society. By assuming that satisfaction comes in a single form, and that it is impossible to compare Jill’s and Jack’s satisfaction indices, Eva liberates humans from having to defend their desires. But, as freedom from other people’s prejudices makes its triumphant entrance, a new form of authoritarianism is breaking in via the back door: The radical ban on evaluating Jill’s joy relative to Jack’s also wrecks any capacity to differentiate between Jill’s experience of wasting away in a Croydon warehouse, working on a zero-hours contract, and Jack’s trading organic fruit in an idyllic Lake District marketplace.

To feel solidarity toward Jill, we would need to compare Jill’s experiences to Jack’s, or at least her satisfaction index to his. But that would open the floodgates of… paternalism. And here is the sheer brilliance of Eva’s model: the same move that stops anyone from censuring Harriet’s desires legitimises Jill’s zero-hour contracts, indeed hides exploitation in plain sight.

Bird No. 2: Her utopic model allows Eva to present herself as the scientist of society who can prove capitalism’s superiority as a mathematical theorem!

Imagine, ladies and gentlemen, that Mussolini, Hitler or the KGB had access to a mathematical proof that their regime was the best of all possible regimes. What an extraordinary propaganda tool it would have been! Eva senses the power that her little model places within her reach – and she goes to town with it.

Of course, no one, not even a Pythagoras on amphetamines, could prove that capitalism is good. Eva knows this. So, she tries out what we Greeks call a paralogy: When you cannot prove something, set out to prove something else that seems close enough. So, unable to prove that capitalism can be civilised, Eva aims to prove that market forces can potentially create circumstances that cannot be improved upon – not the same thing but close enough for her purpose.

Like all mathematical proofs, Eva proceeds one step at a time, like a chess master railroading a novice toward an inevitable check mate. First, she must gain control over the meaning of social improvement. Her suggestion is that social improvement occurs only when some change makes at least one person better off without hurting another. Once she has smuggled into the conversation this not-obviously-unreasonable definition of improvement, she proceeds to prove that it is possible to define immaculate prices for everything on earth– from smart phones and potatoes to theatre tickets, tuition fees and greenhouse gases.

“Immaculate prices?”, I hear you ask. Eva defines them as prices that, were they to prevail in the markets, would guarantee each person maximum satisfaction given the satisfaction of everyone else. Or, to put it differently, prices that could not, given her definition of social improvement, be improved upon!

To Eva, the very thought that such immaculate prices may be possible is all that matters. She overlooks the fact that, in our really-existing capitalism, the prevailing price of labour leaves millions unemployed, the destruction of the planet is ‘free’, and the price people pay for money is the loss of their soul. Eva knows that her immaculate prices will never prevail in any market near her, but this does not shake her faith. They are her holy grail, the divinity and the holy ghost wrapped up in one bundle of sanctity. Like the belief in the existence of god soothes the believer whose prayers go routinely unanswered, the mere possibility of these immaculate prices is enough for Eva to live hopefully in a capitalism that is far from immaculate.

Why? Because she can prove that her imaginary immaculate prices correspond to an imaginary immaculate distribution of wealth and income – one she has proved, with her impressive mathematics, can only be altered at the expense of at least one person. Like the Borg Queen in Star Trek, Eva seeks perfection in a utopia of her making. A model depicting a perfect capitalist universe inhabited by imagined drones whose liberty is as complete as it is pointless.

You may well ask: Who gives a damn? All of us ought to. Eva’s economic model is to the post-Thatcher world what the Bible was in the Middle Ages: the language of power, the syntax and the grammar in which madmen in authority couch matters of state and society, not to mention of finance and other forms of weaponised greed. That this language leaves almost everyone mystified, baffled, disenfranchised and powerless is perhaps its greatest merit.

Once Eva has her proof, her work is done. Not because she has proven capitalism to be good but because, by that point, anyone who has followed her reasoning falls into one of two groups. Those choked by the maths, feeling inadequate and ready to defer to her expert analysis. And the very, very few who, having invested massively in mastering the mathematics, would need a heroic disposition to turn down the power Eva’s model bestows upon them in the universities, government outfits, rating agencies, banks and corporations. In this, we have a propaganda coup superior even to Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will:

The great propaganda value of Eva’s model lies also in the way it harnesses and misdirects the anger it occasions. We feel like shouting: “And what if these immaculate prices are theoretically possible? Who cares? Actual markets are incapable of properly pricing work, trees, even decent food.” Or to get even angrier at the thought that, even if Eva’s immaculate prices do prevail, society can still be pretty disgusting – for example, a world in which I own everything, including all of you, is one where everyone enjoys the greatest satisfaction consistent with not upsetting anyone – me, who owns everything.

At this juncture we must realise we have fallen headlong into Eva’s trap. The question “Can markets be helped to yield immaculate prices, and if so how?” inevitably inspires a technical, non-political discussion leading to an answer involving free-er markets, better markets, more markets, all-singing-all-dancing markets. Nothing is more political and toxic than the belief that highly political choices are apolitical, technical matters to be left to the experts.

Like moths by the fire, we become hypnotised by the mere possibility of un-improvable circumstances under conditions of complete liberty. No discussion of really-existing capitalism is possible once Eva has trapped us in this science fiction where everyone gets as much joy as it is possible without stepping on someone else’s toe. Lured into her labyrinth of deception, we lose sight of how those working for Walmart, Wall Street, Google, Deliveroo or in any Amazon warehouse do not work in any marketplace – that they spend their days and nights in hierarchical organisations more reminiscent of the Chinese People’s Army than a farmers’ market.

On really-existing capitalism

Let us now set aside Eva’s unrealistic utopia and look at the real dystopia that we inhabit and which Eva’s utopia reinforces by making it invisible to those living within.

As long ago as in the 1920s, the rise of networked mega-corporations, of the Edisons and of the Fords, created big business cartels investing heavily into how to usurp states and replace markets. In their wake, banks consolidated and filled the world with fictitious money resting upon mountain ranges of impossible debt. Together, captains of industry and masters of finance accumulated war chests of billions with which to pad campaigns, capture regulators, ration quantities and, in this manner, control prices.

Through interminable mergers and acquisitions, corporations replaced markets by a global Technostructure oozing with the power to shape the future for themselves. And, soon enough, that image was reflected into the soul of everyone. Richard Branson captured that moment with a statement which made William Morris spin in his grave: Who produces stuff and how does not matter one bit. Only brands matter now, opined Sir Richard. Before long, branding took a radical new turn, imparting personality to objects, boosting consumer loyalty and, of course, the Technostructure’s profits. Before they knew it, people felt compelled to re-imagine themselves as brands. The internet allowed colleagues, employers, clients, detractors, and ‘friends’ constantly to survey one’s life, putting pressure on each to evolve into a profile of activities, images, and dispositions that amount to an attractive, sellable brand.

Young women and men lacking a trust fund ended up in one of two dead-ends. Condemned to working under zero-hour contracts and for wages so low that they must work all hours to make ends meet, rendering ridiculous any talk of personal time, space, or freedom. Or forced to invest in their own brand every waking hour of every day, as if in a Panopticon where they cannot hide from the attention of those who might give them a break. Selfies have eroded any meaningful sense of self. Before posting a tweet, watching a movie, sharing a photograph or chat message, they must remain mindful of the networks they please or alienate.

In job interviews enlightened employers invoke utopian ideas of the self instructing them: “Be true to yourself, follow your passions.” Angst-ridden, they redouble their efforts to discover passions that future employers may appreciate, and to manufacture a true self that the job market will want to pay for. They struggle breathlessly to work out what average opinion among opinion-makers believes that average-opinion thinks is the most attractive of their potential true selves. Never slow to miss an opportunity, the Technostructure creates entire industries to guide them on their quest made up of counsellors, coaches and varied ecosystems of substances and self-help.

The larger the Technostructure grew the larger the financial sector necessary to conjure up fictitious capital to fund its largesse. Before we knew it, General Motors turned into a huge hedge fund that also produced some cars on the side. Across the West, the tug-of-war between profits and wages was replaced by the workers’ struggle for credit, for the right to go into debt.

To capture that moment in my book, I gave Eva a life before being an academic. As a theoretical physics graduate, her first job was as a Lehman Brothers’, obscenely-remunerated, graduate. While at Lehman’s she had a task to perform before going home every night to crash out: To leave on her boss’ desk a single-sheet of paper with a single number on it, an estimate of how much money Lehman’s stood to lose during that night while Wall Street was asleep and Asia was humming along. Where did that number come from? It came from the same model economists teach in the departments of our universities.

To compute her magic number, Lehman’s potential losses, Eva had to assume that the Jills and the Jacks of the world not only operated like complicated thermostats aiming at satisfying strictly private desires but that they, also, carried person-specific propensities to go broke. In the same way that the probability of Jill breaking her leg walking in a Glasgow street is independent of the probability that Jack will break his while watching TV in Kentucky, Eva’s model assumed that bankruptcies were independent ‘events’ whose separate probabilities she could compute just like she could calculate the immaculate prices in her little model

Of course, this is not how really-existing capitalism works. When a crisis hits, a chain reaction of bankruptcies feeds off itself. The sudden joblessness of the Jacks shrinks their expenditure and, before they know it, the Jills have lost their businesses. It is as if the legs of all the Jills and Jacks shatter sequentially on different continents, a global chain reaction that would wreck any insurance company in the same way that AIG, the American Insurance Group, was ruined the moment Lehman’s collapsed on the night of 14th September 2008. Naturally, the number that Eva had left on her boss’ desk that evening proved nowhere as astronomic as the actual losses that the first light of day revealed.

And yet, the same failed model was used in 2009, in 2010, today, to justify the bankers’ bailouts and the practices of the powerful today – its power still emanating from its utopian depiction of market capitalism. Under its ideological, theological I should say, cover, the Technostructure is developing new capabilities daily. It can now manufacture not just prices, money, consent but also desires and our self-image. Emasculated prices guarantee its profit. Hyper-complicated debt allows it fully to usurp the state’s monopoly over money. Turning over the private realm into a digital Panopticon destroys resistance to its authority and enables history’s greatest, and most cynical, transfer of banking losses from the books of the culprits to the shoulders of their innocent, struggling victims.

In my book, Costa, the brilliant engineer who can see through Eva’s models, experiences mental distress that only poetry, music and science fiction can ameliorate. A futurist since birth, he is weighed down by the increasing realisation that the future is no longer what it was cracked up to be – an insight that he first had in 1977, the year his beloved Sex Pistols released No Future as if to close the chapter on Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto of 1909. To counter the sinking feeling he invents a machine whose malfunction allows my book’s characters to glean fragments from an alternative historical trajectory. What that alternative present looks like I am as eager to find out as you are – come next December when I am contracted to submit the manuscript to my publisher.

Conclusion: To show the heavens more just

At this point, it is incumbent upon me to address the unconverted. Those amongst you who have tolerated me so far even though myt take on capitalism leaves you bemused. There are plenty of good people, Steven Pinker for example, who would think of my musings as utterly whacky. They ask: How can you say that you care about the weak and the poor but not see that the proportion of people living in poverty collapsed from 94% in 1820 to around 10% in the 21st century precisely because of capitalism? Sure, inequality rose at the same time but it did so as a result of the same forces which crushed abject poverty. They concede that, yes, humanity can do much better in distributing wealth, but only by improving upon capitalism, not chucking it.

The problem with such statistics is that they are meaningless unless we are determined to look to the past and see a poorer version of the present. In the mind of mainstream thinkers, values that do not translate into prices are mirages, superstitions. To the extent that they have a few dollars in their pockets, Australia’s Aborigines today appear to them better off than before Captain Cook disembarked on their shores. What if they lived happy and fulfilled lives before money, guns, private property and killer germs arrived from England? In Eva’s viewfinder, where money is the sole metric of wealth, the destruction of Aboriginal communal living, their enslavement, appears as liberation from poverty.

What actually happened between 1820 and now was the transformation of communities in which most people lived reasonably well with hardly any need for money into capitalist societies where most people struggle to survive with some money, sometimes with loads-a-money. Poverty was invented, not ameliorated, by capitalism. Nonetheless, it would be an error to say that the past was better. As a feminist, freedom-junkie, a radical democrat, I cannot bring myself to praise a past that I would not want to inhabit.

I do, indeed, believe that people are now broadly healthier, better educated and in important ways freer than in 1820. Whether we are happier or richer than our ancestors, I cannot tell – except for the indigenous peoples decimated by Europeans who have every reason to look to their past as heavenly. What infuriates me about Eva and her ilk, more than their fixation with measurable wealth, is the stunning complacency. Everything good that has happened in history, happened because someone got pissed off and said: “This is hideous, I won’t stand for it.” The dominant economic paradigm, in contrast, adopts a utopic view of the present to back an inexcusable status quo.

If there is a Shakespeare character that I pity, it was King Lear, especially at the moment when, having lost power, home and shelter, he identifies with the poor – lamenting that he did not, while he still could, “shake the superflux to them” … “And show the heavens more just.”

Shaking the superflux, re-distributing wealth, would be a fine ambition if the problem was that it fell unequally upon us, like manna from a heaven unjust. But this is pie in the sky. Less than five percent of new global wealth ever reaches the poorest sixty percent of humanity. Why? Because, unlike the distribution of blue and brown eyes amongst new-borns, this is nothing like a natural phenomenon. Inequality prevails and grows because the people producing most of the food, clothes and gadgets on which modern society turns are forced by necessity to toil like their parents and grandparents had done in factories, farms and mines belonging to an oligarchy creaming the profits.

Enlightened Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, like Bill Gates, and financiers, like Warren Buffet, are Lear’s progenies, their concern for inequality’s triumph an endorsement of the fallen king’s call to shake the superflux. They disdain inequality but heavens forbid that we shall speak of capitalism whose side-effect inequality is. That’s why I dislike King Lear, the play. Coriolanus, on the other hand, epitomises the desolation of any individualism denying the person the benefits of catching a glimpse of one’s self in the eyes of others, of our community. In Coriolanus citizens demand a society without exploitation but also understand that forging consensus, let along collective action, is a difficult and dangerous endeavour.

No mechanism for re-distributing the lords’ loot could have put Lear’s world right any more than Hamlet could have civilised the Kingdom of Denmark. In Lear’s world, as in our financialised capitalism, the forces of evil band together effortlessly and coordinate spontaneously. When at their most dangerous, they even take aim at inequality. Was it not Mussolini who set up the first universal pension system in Europe? Where the Nazis not railing against the inequality caused by the bankers in the 1920s? Did Donald Trump not look into the eyes of forsaken blue-collar workers before promising to look after them, to make them proud again?

To conclude, making the heavens more just, rebelling against what lies behind the unshaken superflux, requires virtuous rebels who use their autonomy to link with others, to create something larger than themselves but without losing themselves in that ‘something’ and without helping the serpent’s egg hatch in the warm glow of an authoritarian egalitarianism.

This task seems at once essential and impossible. It is a feeling that paralyses and helps the status quo prevail. The question is: What social arrangements, what type of property rights, what collective action mechanisms can we envision so as both to overcome Popper’s and Marx’s objections to utopias AND allow us to escape the current dystopia?

I remember years ago I was addressing a political meeting at the time of Occupy Wall Street, in which I argued for the enlisting of financial engineering and of digital technologies in the struggle to prevent the re-establishment of what I called Bankruptocracy – of rule by the most bankrupt of banks. A member of the audience was deeply unimpressed and told me, in a hostile tone: “Science fiction fantasies are an indulgence when people are hurting, mate.”

For a moment I thought he was right. But I caught myself answering something like: Capitalism and science fiction share one thing: they trade in future assets using fictitious currency. Even if the tools I speak of are still in the realm of science fiction, we need to develop and to deploy them before they are used to reinforce a dystopia functional to the interest of the very few.”

I suppose that the little, unfinished book that you kindly allowed me to talk to you about tonight is evidence that I still believe we face a stark choice between (A) science fictions that are being deployed to maintain a clinically deceased dystopia and (B) science fictions that can help a realistic utopia be born.

Thank you!