From Lars Syll As a result of the three waves of new classical economics, the field of macroeconomics became increasingly rigorous and increasingly tied to the tools of microeconomics. The real business cycle models were specific, dynamic examples of Arrow–Debreu general equilibrium theory. Indeed, this was one of their main selling points. Over time, proponents of this work have backed away from the assumption that the business cycle is driven by real as opposed to monetary forces, and they have begun to stress the methodological contributions of this work. Today, many macroeconomists coming from the new classical tradition are happy to concede to the Keynesian assumption of sticky prices, as long as this assumption is imbedded in a suitably rigorous model in which economic actors

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Lars Syll

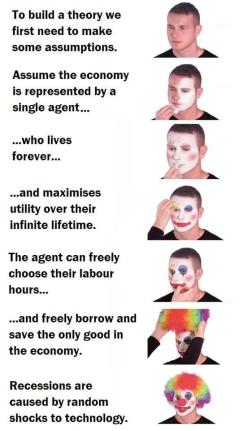

As a result of the three waves of new classical economics, the field of macroeconomics became increasingly rigorous and increasingly tied to the tools of microeconomics. The real business cycle models were specific, dynamic examples of Arrow–Debreu general equilibrium theory. Indeed, this was one of their main selling points. Over time, proponents of this work have backed away from the assumption that the business cycle is driven by real as opposed to monetary forces, and they have begun to stress the methodological contributions of this work. Today, many macroeconomists coming from the new classical tradition are happy to concede to the Keynesian assumption of sticky prices, as long as this assumption is imbedded in a suitably rigorous model in which economic actors are rational and forward-looking.

Well, rigour may be fine, but how about reality?

Real business cycle theory — RBC — is one of the theories that has put macroeconomics on a path of intellectual regress for three decades now. And although there are many kinds of useless ‘post-real’ economics held in high regard within mainstream economics establishment today, few — if any — are less deserved than real business cycle theory.

The future is not reducible to a known set of prospects. It is not like sitting at the roulette table and calculating what the future outcomes of spinning the wheel will be. So instead of — as RBC economists do — assuming calibration and rational expectations to be right, one ought to confront the hypothesis with the available evidence. It is not enough to construct models. Anyone can construct models. To be seriously interesting, models have to come with an aim. They have to have an intended use. If the intention of calibration and rational expectations is to help us explain real economies, it has to be evaluated from that perspective. A model or hypothesis without specific applicability is not really deserving of our interest.

Without strong evidence, all kinds of absurd claims and nonsense may pretend to be science. We have to demand more of a justification than rather watered-down versions of ‘anything goes’ when it comes to rationality postulates. If one proposes rational expectations one also has to support its underlying assumptions. None is given by RBC economists, which makes it rather puzzling how rational expectations has become the standard modelling assumption made in much of modern macroeconomics. Perhaps the reason is that economists often mistake mathematical beauty for truth.

In the hands of Lucas, Prescott and Sargent, rational expectations have been transformed from an – in-principle – testable hypothesis to an irrefutable proposition. Believing in a set of irrefutable propositions may be comfortable – like religious convictions or ideological dogmas – but it is not science.

So where does this all lead us? What is the trouble ahead for economics? Putting a sticky-price DSGE lipstick on the RBC pig sure won’t do. Neither will — as Paul Romer noticed — just looking the other way and pretend it’s raining:

The trouble is not so much that macroeconomists say things that are inconsistent with the facts. The real trouble is that other economists do not care that the macroeconomists do not care about the facts. An indifferent tolerance of obvious error is even more corrosive to science than committed advocacy of error.