According to some economists, ‘Divisia money’ is, as a monetary aggregate, a superior and neoclassical alternative to the more often used M2 or M3 ‘single sum’ aggregates. But looking at such money aggregates in isolation prevents economists from analyzing monetary developments using the integrated and statistically coherent Flow of Funds framework which ties the growth of money to the growth of credit. Divisia money is not a sound alternative. The Flow of Funds are. The graph shows that aggregate lending data are much more indicative of the growth of financial vulnerabilities and booms and busts than data on money. What is Divisia money? Divisia money is a neoclassical alternative to the classical ‘single sum’ money aggregates, like M3, pioneered by Keynes in ‘A treatise on Money

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

According to some economists, ‘Divisia money’ is, as a monetary aggregate, a superior and neoclassical alternative to the more often used M2 or M3 ‘single sum’ aggregates. But looking at such money aggregates in isolation prevents economists from analyzing monetary developments using the integrated and statistically coherent Flow of Funds framework which ties the growth of money to the growth of credit. Divisia money is not a sound alternative. The Flow of Funds are.

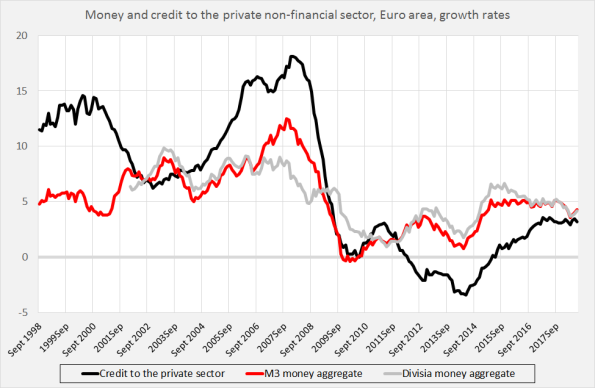

The graph shows that aggregate lending data are much more indicative of the growth of financial vulnerabilities and booms and busts than data on money.

- What is Divisia money?

Divisia money is a neoclassical alternative to the classical ‘single sum’ money aggregates, like M3, pioneered by Keynes in ‘A treatise on Money and made popular by, among others, Friedman and Schwartz. It tries to correct some of the drawbacks of these single sum aggregates but it still suffers from the same ‘ills and fevers’ as the Friedman/Schwartz interpretation of ‘single sum’ money aggregates. The fundamental problem: Divisia money aggregates still look at aggregate money in isolation and not as a variable embedded in a sound monetary framework enabling us to couple aggregated sectoral flows of different kinds of credit to aggregate money. FYI: the ECB publishes such embedded data every month. These are based on the very framework which Divisia money ignores: the flow of funds. This overarching framework already existed in 1963, when Friedman and Schwartz published their masterly monograph ‘A monetary history of the USA‘. Brilliant as it this book is it was also outdated before it was published. As the overarching framework of the Flow of Funds was not used for the interpretation of the results.

2. The concept and operationalization of the Divisia money aggregate

According to neoclassical econometrists, USA edition, ‘single sum’ aggregates of money contain little to no information on business cycles. Outside of the USA, economists are less sure of this (here and here). Why this difference? Friedman and Schwartz already made a difference between what nowadays is called ‘financial cycles’ (look here) and ‘normal business cycles’. The behavior of the money aggregate was, and is, quite different during the financial cycle than during the normal business cycle. As USA neoclassical econometrists focused on ‘normal’ business cycles, they found little information in the monetary aggregates. This finding did not square with the intuitions of many an economist which is why they developed a new aggregate: Divisia money. The intuition behind this: a 500,– Euro note will be mainly used for hoarding, not for transactions and should, hence, not be included into monetary aggregates used to gauge the transaction economy. Different kinds of money have different kinds of velocity. Conceptually, Divisia money distinguishes a large number of monies (1 cent pieces, 2 cent pieces, 5 cent pieces, deposit money on different kinds of deposits and so forth) and suggests attaching a weight to all of these kinds of money; the money aggregate is the sum of the weighted monies. The operationalization is a bit less detailed, as somewhat larger categories are used (cash, different kinds of deposit money). Also, the interest on monies is used to calculate the weights. To be clear: single sum aggregates attaches weights too, but these are either 1 (in the case of Euro’s included in the aggregate) or 0 (in the case of Euro’s which are not included in the aggregated, like Euro’s in the vaults of ATP’s). What Divisia money does not do is to connect money to credit.

3. As is well known, deposit money is created by bank lending. This idea is embedded in the monthly press release of the ECB (already mentioned) which is of course based upon the Flow of Funds. Different kinds of credit and different money flows are estimated to arrive at an estimate of the amount of M3-money. This is not different form what happens at the Fed, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England and so on. Money is estimated using a coherent quadruple accounting framework showing lending as well as borrowing and lenders as well as borrowers. The graph at the beginning of this post shows the growth of Divisia money, the growth of M3 money and the growth of lending to the non-financial private sector (households, non-financial companies). It’s clear that the lending data are much more indicative of financial and disequilibrium developments than the increase of Divisia money and even M3-money. Looking at these aggregates in isolation is when it comes to monetary analysis outright dangerous and has to be rejected. The discussion is not about ‘single sum’ or ‘Divisia’ aggregates. It’s about monetary developments, including lending and borrowing. That’s what the USA econometrists should have analyzed. They didn’t and followed ideas which were already outdated in 1963. Look here for Minsky’s 1963 take on money and credit – it’s not that they could not have known. Alas, before 2009 the European Central Bank used a largely neoclassical interpretation of monetary data, largely ignoring the credit data readily at their disposal. They could have known, too. And we should know.