There was an interesting Twitter spat that, aside from personal nonsense, raised a pretty interesting question – do recessions need to happen? There tend to be two views on the subject with one side claiming that recessions are a healthy sort of “cleansing” part of the business cycle and the other side tends to argue that policymakers could smooth the business cycle so that recessions become a thing of the past.¹ First, it’s helpful to understand the terms we’re using here because they’re a bit vague. So, when we talk about “business cycles” we aren’t really talking about anything that cyclical. The economy tends to trend, not cycle. Here’s a visual of the fluctuations in NGDP for the USA: (Nominal GDP is much smoother than most people might think) For the most part the US economy

Topics:

Cullen Roche considers the following as important: Most Recent Stories

This could be interesting, too:

Cullen Roche writes Understanding the Modern Monetary System – Updated!

Cullen Roche writes We’re Moving!

Cullen Roche writes Has Housing Bottomed?

Cullen Roche writes The Economics of a United States Divorce

There was an interesting Twitter spat that, aside from personal nonsense, raised a pretty interesting question – do recessions need to happen? There tend to be two views on the subject with one side claiming that recessions are a healthy sort of “cleansing” part of the business cycle and the other side tends to argue that policymakers could smooth the business cycle so that recessions become a thing of the past.¹

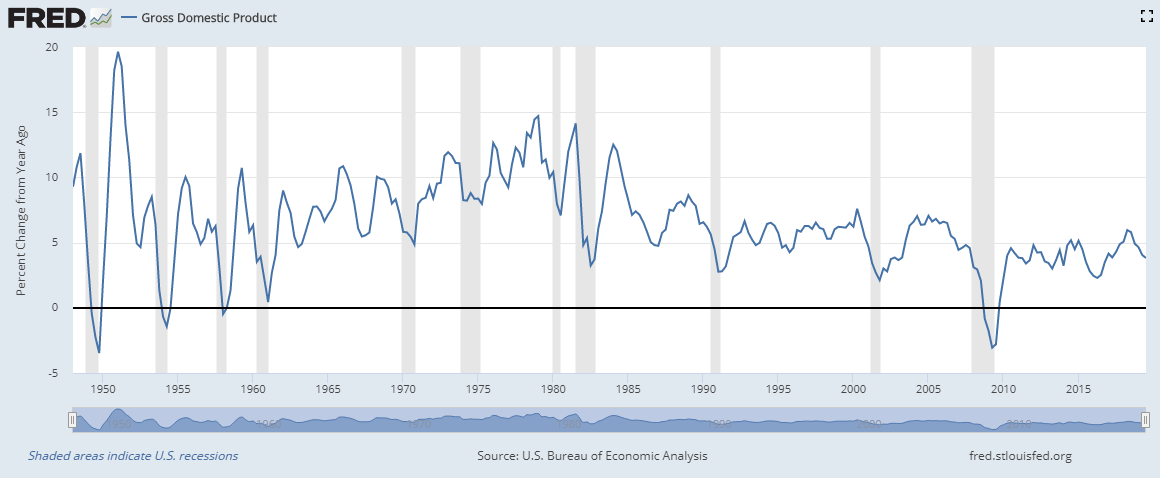

First, it’s helpful to understand the terms we’re using here because they’re a bit vague. So, when we talk about “business cycles” we aren’t really talking about anything that cyclical. The economy tends to trend, not cycle. Here’s a visual of the fluctuations in NGDP for the USA:

(Nominal GDP is much smoother than most people might think)

For the most part the US economy stopped being super cyclical in the post-war era. Now it tends to trend and get shocked. This actually makes sense and in my view is consistent with an economy that is more advanced, diverse and financialized.

There’s something else interesting in that chart though – recessions aren’t necessarily declines in growth. Instead, they’re mostly slowdowns. The NBER’s definition of “recession” has also had to change in time with this to reflect slowdowns rather than declines. With the exception of the financial crisis none of the post-war recessions were actual year over year declines in GDP.

With all that out of the way we can explore the subject at hand – do recessions need to happen? Clearly, from the data above, the economy does not have to undergo periods of negative growth. It might slow down, but we don’t need sustained periods of decline. In theory, the economy could just keep trending in perpetuity. Again, this makes sense for a highly diverse economy that has so many uncorrelated industries that they often offset one another in terms of how they grow and how fast they grow. But theory isn’t reality and in reality the economy does tend to boom and bust in large part because its operators overreact at times.

Since the financial crisis the recessionary theory of booms and busts has become popular again. This theory has always made sense in my mind for developed credit based economies because the credit cycle tends to contribute to excesses that lead to contractions. When those credit excesses are tied to the real economy in a significant way (think, extending credit to new dot com corporations that are unreasonably valued or people who bid up house prices unsustainably) then you often get a bust. Of course, the economy is a lot more complex than that, but for a diverse and financialized economy the credit system becomes an essential component of how it expands and potentially contracts. Add in the craziness of its participants and you can get unsustainable short-term booms that result in short-term busts.

Some interesting research has been done on these matters in recent years. Two notable views are the Forest Fire Theory and the Plucking Theory (not actually new, but being expanded on). The Forest Fire Theory states that the economy becomes more fragile as an expansion occurs in much the same way that a forest without rain becomes more susceptible to forest fires. In other words, the idea is that the length of an expansion correlates with the probability of a downturn. This seems intuitive but there doesn’t appear to be strong evidence to support this view. Therefore, we can conclude that there’s little sense in the idea that “expansions die of old age”. This is of particular interest given that we’re currently in the longest US expansion.

The Plucking Theory is based on Milton Friedman’s old work which states that the economy mostly operates at full capacity and just sort of trends and then gets “plucked” lower like a guitar string. The cause can vary, but the economy tends to revert back just like a guitar string. While the evidence to support this view is stronger than the forest fire theory it does appear that a large recession can pluck us into a different equilibrium. In other words, if the string gets plucked hard enough it might weaken and not pluck all the way back to where it was previously. That would seem to be consistent with the way growth has occurred since the GFC.

My view is not far from the Friedman Plucking Theory except that I would argue that the Plucking Theory doesn’t fully appreciate the extent to which certain members of our economic band might overreact, get a little too excited during the good music, upgrade their instruments on credit, pluck those new strings a little too hard during the good songs and contribute to the potential risk that their strings break. This, to me, is a perfectly rational and empirically supported view of recessions. In any credit based modern monetary system there will be a tendency to loosen credit when times are good and borrow more in the short-term than we can sustain in the long-term. When and if that occurs in a meaningful way, it could contribute to the increasing risk of a recession, especially if those credit instruments are attached to more volatile market based instruments like stocks and real estate.

In sum, what all of this means is that recessions likely aren’t a curable disease even if we’ve done many things to lessen their impacts. Further, there’s no reason why an economy can’t trend in perpetuity. And lastly, the seeds of a bust are likely to be sewn in the boom. In most modern credit based economies that will tend to be an overexpansion of credit somewhere in the financial system. If that boom is truly an unsustainable short-term boom then there is a sense of “cleansing” in the downturn in that it cleans out the bad credit. And as long as the band members are emotional apes there will be a strong probability of overreacting at times, especially when the music gets really good. And that is ultimately why economies will always boom and bust.

¹ – I should add that I tend to think these two views are overstated. Governments probably can’t eliminate fluctuations in the business cycle without automating the entire economy. This doesn’t mean there isn’t reasonable policy to implement, however. Further, as it pertains to the idea of an economic cleansing, I think this view is generally too pessimistic. Permabears tend to see a necessary cleansing in every boom when the reality is that most booms are mostly just long-term trends.²

² – Oh, yummy. A footnote inside a footnote. Reading this far into one of my articles is like stepping on a booby trap. A lot of the views around cleansing seem to be based on our misguided obsession with the Fed, QE and interest rates. As I’ve noted on many occasions, I think the power of these tools is vastly overstated in general. And so you tend to get lots of people overreacting to their implementation and creating narratives that sound appealing (like asset inflation, interest rate manipulation, etc), but are mostly overblown.

NB – Here’s a cute picture of my dog.