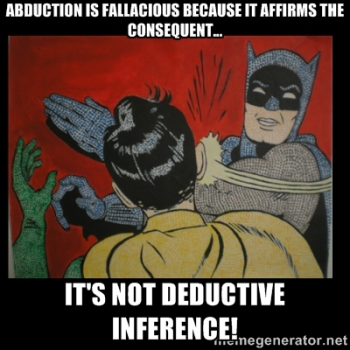

Mainstream economics — going for the wrong kind of certainty In science we standardly use a logically non-valid inference — the fallacy of affirming the consequent — of the following form: (1) p => q (2) q ————- p or, in instantiated form (1) ∀x (Gx => Px) (2) Pa ———— Ga Although logically invalid, it is nonetheless a kind of inference — abduction — that may be factually strongly warranted and truth-producing. Following the general pattern ‘Evidence => Explanation => Inference’ we infer something based on what would be the best explanation given the law-like rule (premise 1) and an observation (premise 2). The truth of the conclusion (explanation) is nothing that is logically given, but something we have to justify, argue for, and test in different ways to possibly establish with any certainty or degree. And as always when we deal with explanations, what is considered best is relative to what we know of the world. In the real world all evidence has an irreducible holistic aspect. We never conclude that evidence follows from a hypothesis simpliciter, but always given some more or less explicitly stated contextual background assumptions. All non-deductive inferences and explanations are necessarily context-dependent.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics, Theory of Science & Methodology

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Mainstream economics — going for the wrong kind of certainty

In science we standardly use a logically non-valid inference — the fallacy of affirming the consequent — of the following form:

(1) p => q

(2) q

————-

p

or, in instantiated form

(1) ∀x (Gx => Px)

(2) Pa

————

Ga

Although logically invalid, it is nonetheless a kind of inference — abduction — that may be factually strongly warranted and truth-producing.

Following the general pattern ‘Evidence => Explanation => Inference’ we infer something based on what would be the best explanation given the law-like rule (premise 1) and an observation (premise 2). The truth of the conclusion (explanation) is nothing that is logically given, but something we have to justify, argue for, and test in different ways to possibly establish with any certainty or degree. And as always when we deal with explanations, what is considered best is relative to what we know of the world. In the real world all evidence has an irreducible holistic aspect. We never conclude that evidence follows from a hypothesis simpliciter, but always given some more or less explicitly stated contextual background assumptions. All non-deductive inferences and explanations are necessarily context-dependent.

Following the general pattern ‘Evidence => Explanation => Inference’ we infer something based on what would be the best explanation given the law-like rule (premise 1) and an observation (premise 2). The truth of the conclusion (explanation) is nothing that is logically given, but something we have to justify, argue for, and test in different ways to possibly establish with any certainty or degree. And as always when we deal with explanations, what is considered best is relative to what we know of the world. In the real world all evidence has an irreducible holistic aspect. We never conclude that evidence follows from a hypothesis simpliciter, but always given some more or less explicitly stated contextual background assumptions. All non-deductive inferences and explanations are necessarily context-dependent.

If we extend the abductive scheme to incorporate the demand that the explanation has to be the best among a set of plausible competing/rival/contrasting potential and satisfactory explanations, we have what is nowadays usually referred to as inference to the best explanation.

In inference to the best explanation we start with a body of (purported) data/facts/evidence and search for explanations that can account for these data/facts/evidence. Having the best explanation means that you, given the context-dependent background assumptions, have a satisfactory explanation that can explain the fact/evidence better than any other competing explanation — and so it is reasonable to consider/believe the hypothesis to be true. Even if we (inevitably) do not have deductive certainty, our reasoning gives us a license to consider our belief in the hypothesis as reasonable.

Accepting a hypothesis means that you believe it does explain the available evidence better than any other competing hypothesis. Knowing that we — after having earnestly considered and analysed the other available potential explanations — have been able to eliminate the competing potential explanations, warrants and enhances the confidence we have that our preferred explanation is the best explanation, i. e., the explanation that provides us (given it is true) with the greatest understanding.

This, of course, does not in any way mean that we cannot be wrong. Of course we can. Inferences to the best explanation are fallible inferences — since the premises do not logically entail the conclusion — so from a logical point of view, inference to the best explanation is a weak mode of inference. But if the arguments put forward are strong enough, they can be warranted and give us justified true belief, and hence, knowledge, even though they are fallible inferences. As scientists we sometimes — much like Sherlock Holmes and other detectives that use inference to the best explanation reasoning — experience disillusion. We thought that we had reached a strong conclusion by ruling out the alternatives in the set of contrasting explanations. But — what we thought was true turned out to be false.

That does not necessarily mean that we had no good reasons for believing what we believed. If we cannot live with that contingency and uncertainty, well, then we are in the wrong business. If it is deductive certainty you are after, rather than the ampliative and defeasible reasoning in inference to the best explanation — well, then get in to math or logic, not science.