From David Ruccio Almost five years ago, I suggested we start calling things by their correct names. Take the working-class—people who are forced to have the freedom to sell their labor power for a wage. We refer to them as members of the middle-class (which needs to be “rebuilt“) and working families (who need to be helped) or, now as workers’ wages stagnate and the real value of the minimum wage declines, as the “feral underclass” (especially in theUK, in the aftermath of the riots) or the working-age poor (as in the recent AP report on the demographic composition of those living in poverty [ht: ja]).* What’s the problem with calling it as it is? What are we afraid of? It’s the working-class, and its member are becoming increasingly impoverished. People who work for a living, or want a full-time job but can’t find one (whether or not they’re actively looking for one, since it’s getting increasingly difficult to find a decent job), represent nearly 3 out of 5 poor people. . . So, from now on, in political and economic discourse, let’s call things by their correct names. The vast majority of people in the United States are members of the working-class. And they’re getting shafted. Well, it seems, Americans are still struggling with the notion of the working-class (and of class more generally).

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Almost five years ago, I suggested we start calling things by their correct names.

Take the working-class—people who are forced to have the freedom to sell their labor power for a wage. We refer to them as members of the middle-class (which needs to be “rebuilt“) and working families (who need to be helped) or, now as workers’ wages stagnate and the real value of the minimum wage declines, as the “feral underclass” (especially in theUK, in the aftermath of the riots) or the working-age poor (as in the recent AP report on the demographic composition of those living in poverty [ht: ja]).*

What’s the problem with calling it as it is? What are we afraid of? It’s the working-class, and its member are becoming increasingly impoverished. People who work for a living, or want a full-time job but can’t find one (whether or not they’re actively looking for one, since it’s getting increasingly difficult to find a decent job), represent nearly 3 out of 5 poor people. . .

So, from now on, in political and economic discourse, let’s call things by their correct names. The vast majority of people in the United States are members of the working-class. And they’re getting shafted.

Well, it seems, Americans are still struggling with the notion of the working-class (and of class more generally).

The best Donald Trump was able to come up with were “the great miners and steel workers of our country.” (Really? Trump wants to send American workers back into the mines and steel mills? Those jobs are mostly gone, and that’s a good thing.) Even Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders weren’t able to refer to the working-class, preferring instead to use terms like “working people,” “hard-working families,” “workers,” and “working families”—although, in their case, when counterposed to corporate profits and CEOs, it was pretty clear they were referring to the growing class divide in the United States.

As Tamara Draut [ht: ja] explains, the American working-class is in fact changing.

the blue-collar, hard-hat, mostly male archetype of the great post-war prosperity — is long gone. In its place is a new working class whose jobs are in the now massive sectors of our serving and caring economy. And so far, neither Trump nor Clinton have talked about this new working class, which is much more female and racially diverse than the one of my dad’s generation. With Trump’s racially charged and nativistic rhetoric, he’s offering red meat to a group of Americans who have every right to be angry — but not at the villains Trump has served up.

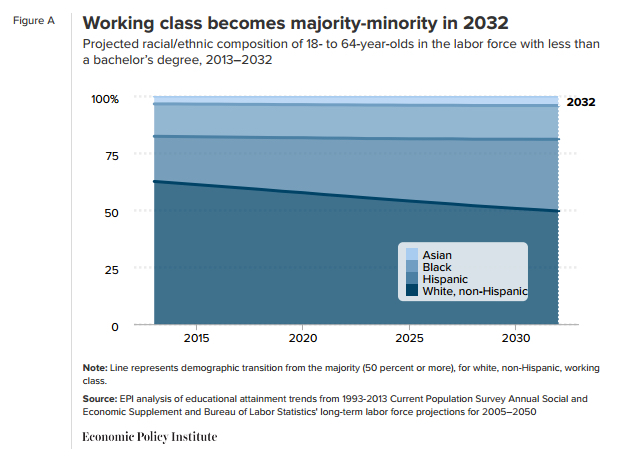

“Long gone” may be an exaggeration. There are still more than 12 million workers employed in manufacturing in the United States (out of a total of 150 million employed people). And, according to the Economic Policy Institute (pdf), the American working class (which they define as people with less than a bachelor’s degree) is still a majority non-Hispanic white.* (It is projected to become majority people of color in 2032.)

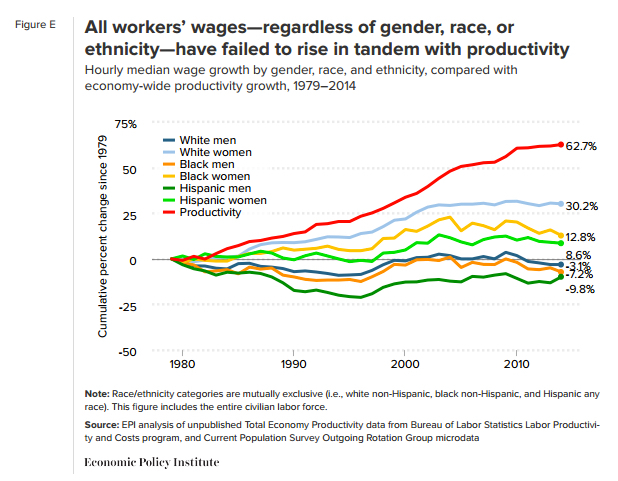

What we have, then, is an increasingly diverse working-class that together, “regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender,” has been receiving wages that fall far short of increases in productivity for more than three decades.

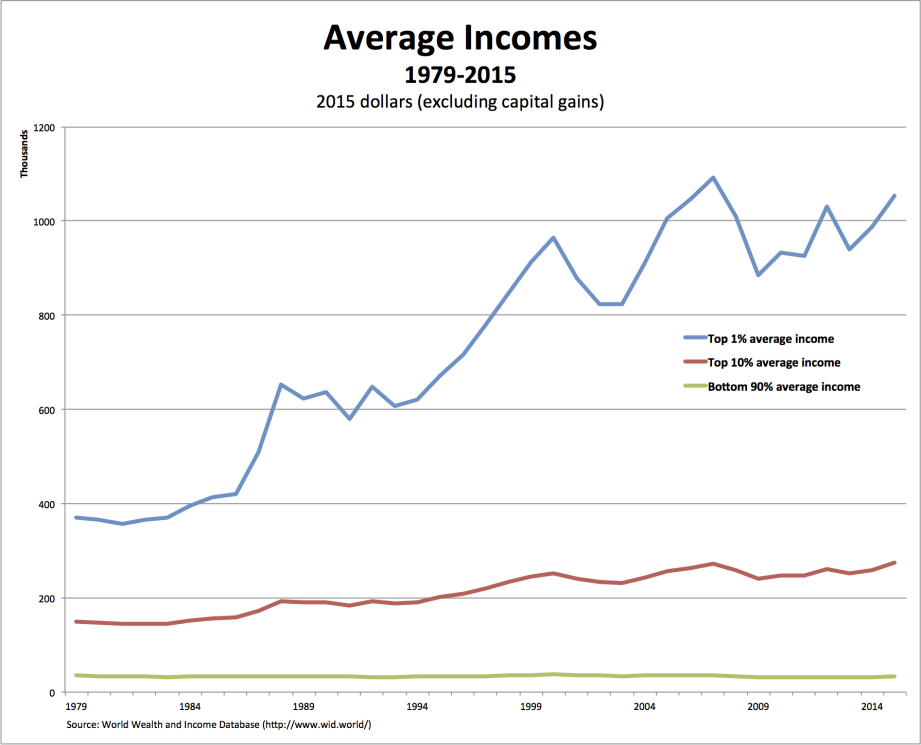

The result, as I showed earlier this month, is that

the average income of the bottom 90 percent fell between 1979 and 2015 (from $34.6 thousand to $33.2 thousand), while the average income of the top 10 percent rose (from $149.1 thousand to $273.8 thousand) and that of the top 1 percent soared (from $370.2 thousand to over $1 million).

That dramatic rise in inequality—along with, as Dustin Guastella explains, “the rise of precarious labor, the proletarianization of white-collar work, the rise in real unemployment, [and] the persistence of underemployment—are what have propelled class issues back into the public debate.

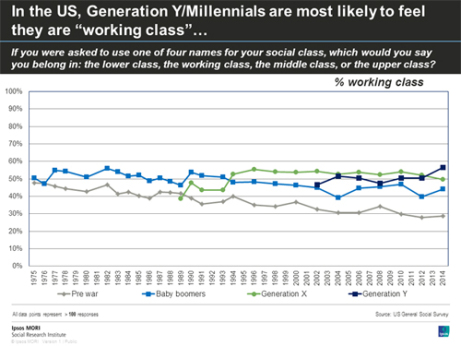

That combination is certainly what has convinced Millenials, the members of Generation Y, to see themselves less as middle-class and more as working-class. They may be better educated than their predecessors and for the most part they’re not working in traditional working-class jobs (like manufacturing or other blue-collar tasks) but their low wages and precarious employment make them identify with the working-class—”a feat in and of itself considering the narrow American cultural understanding for who qualifies as working class.”

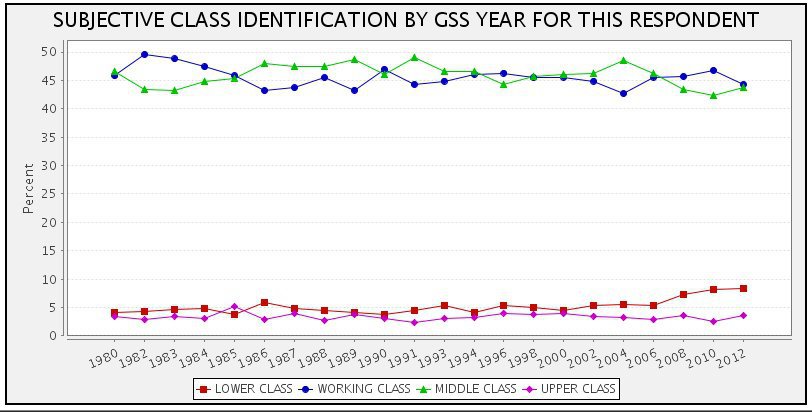

The fact is, as many Americans self-identify as working-class as they do middle-class, which is “striking given how uncommon the term working class seems to be in both the media and political speech these days.”

As I argued a year and a half ago,

Our political language has served to ignore the working-class status of most so-called middle-class Americans and, as a result, to confine the working-class (understood as workers without a college education), when it is mentioned at all, to a relatively small segment of the population. In other words, the working-class has come to be defined as the working-poor and the middle-class as something else.

As I see it, we’ll get a more accurate representation of our economic and political landscape if we redefine what we mean by the working-class. The fact is, what others understand to be working-class and middle-class actually have a lot in common. They may have different levels of education (high school, a year or two of college, and a four-year college degree), different color collars (blue, pink, and white), and work in different sectors (manufacturing and services, private and public) but they’re all pretty much in the same boat: they are forced to sell their ability to work to someone else in order to make enough money to support themselves and their families. That’s a very large part of the population. It basically excludes two relatively small groups: the capitalists at the top (who get the profits) and managers and supervisors (who manage the labor of others and get a cut of the profits).

So, we’re talking about 80 or so percent of Americans who, in one way or another, are members of the working-class.

They know it and we know it—even as mainstream economists, politicians (both liberal and conservative), and social surveys downplay or deny the existence of a large and increasingly distressed American working-class.

The next question then is, what kind of language are we going to use to characterize the not-working-class, the class that takes and otherwise lives off the surplus produced by the working-class? Right now, we have the “upper class” and, more recently, the “1 percent” and the “billionaire class.” Clearly, we need something better, a term that describes not just the rung at the top of the income ladder but a place in relation to that of the working-class, thus giving us a pair of positions that define the central relationship within the current economic system.

It’s going to take more than a bit of struggle. But, once we have that term, we’ll be well on our way to calling things by their correct (class) names.

*And that’s one of the reasons the presidential race right now is so close. Trump leads among white registered voters without a college degree, a significant portion of the working-class, by a margin of 58 percent to 30 percent.