Supermarket executives were up on Parliament Hill this week, appearing before the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food’s inquiry into food inflation grocery chain profits. They repeated the now-familiar argument that supermarkets have not caused food inflation, they have merely passed along higher input costs to their customers; their profit margins have been stable, it is claimed. Don’t believe them. Here are a few data points on the argument that the chains haven’t actually profited from inflation, since their profit margin has (supposedly) stayed the same. Here’s why I think that argument is not convincing: 1. Grocery store margins HAVE increased notably since the pandemic. The arguments we’ve heard this week are usually based on year-over-year changes in margins,

Topics:

Jim Stanford considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Supermarket executives were up on Parliament Hill this week, appearing before the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food’s inquiry into food inflation grocery chain profits. They repeated the now-familiar argument that supermarkets have not caused food inflation, they have merely passed along higher input costs to their customers; their profit margins have been stable, it is claimed.

Don’t believe them. Here are a few data points on the argument that the chains haven’t actually profited from inflation, since their profit margin has (supposedly) stayed the same. Here’s why I think that argument is not convincing:

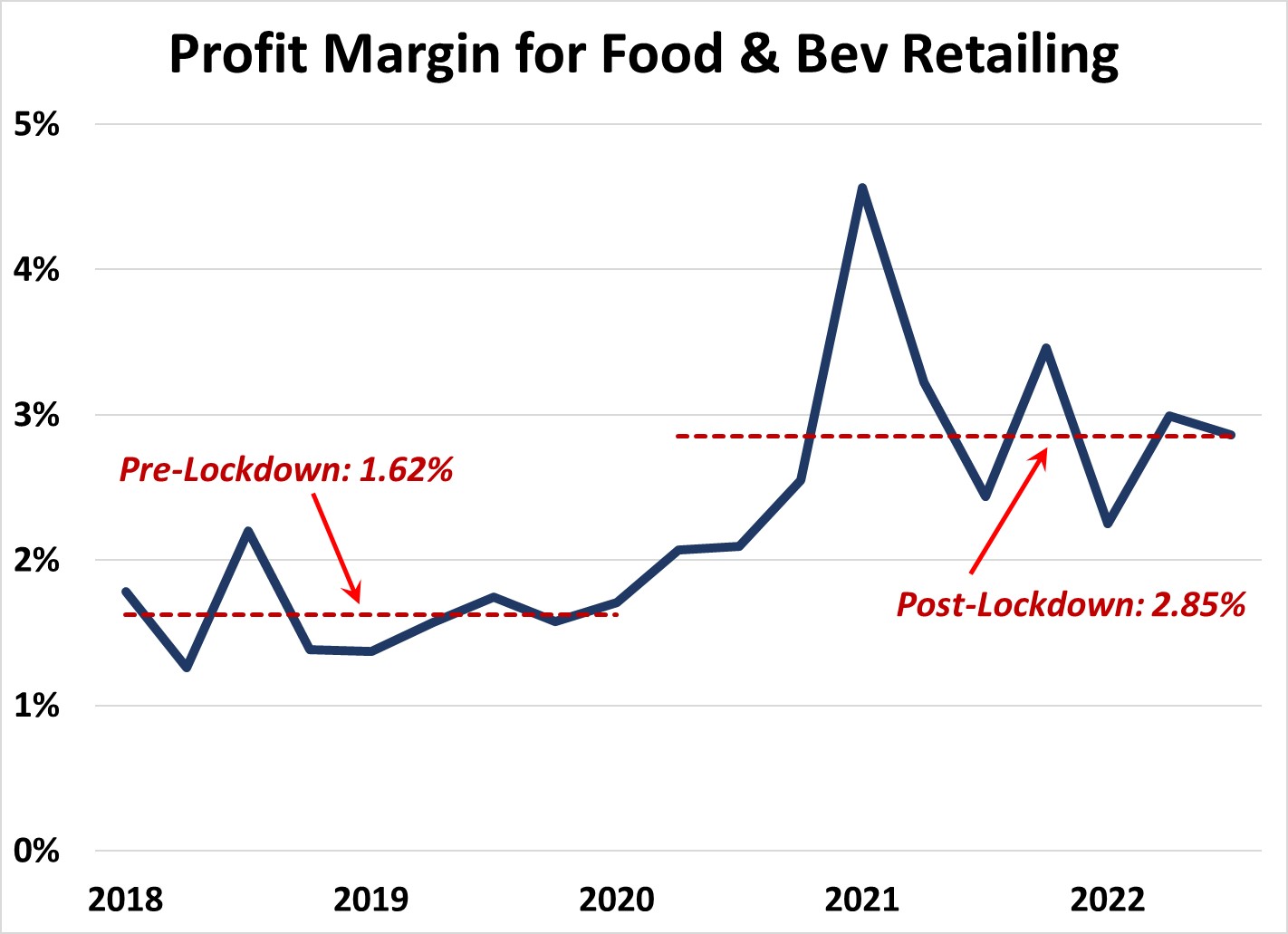

1. Grocery store margins HAVE increased notably since the pandemic. The arguments we’ve heard this week are usually based on year-over-year changes in margins, given the controversy that’s erupted in Parliament this year. They argue margins haven’t changed much OVER THE LAST YEAR. That’s true. But the BIG increase in grocery store margins was earlier in the pandemic: amidst the panic, toilet paper hoarding, and other unique circumstances of the lockdowns. Margins jumped, and have stayed high relative to historical norms — even after economic re-opening and ‘normalization’.

Here’s the industry-wide margin for food & beverage retailing from Stats Can. The margin (after tax net income as share total revenue) jumped in mid-2020, and has stayed high. The average margin since the lockdowns is three-quarters higher than in the period 2018 to 1Q 2020 (2.85% since 2Q20, vs. 1.62% before). That increase is even bigger if you use a longer pre-COVID average (eg. back to 2015). Company-specific financial data shows a similar trend (not surprisingly, since the 5 biggest chains make up 80% of that Stats Can industry total).

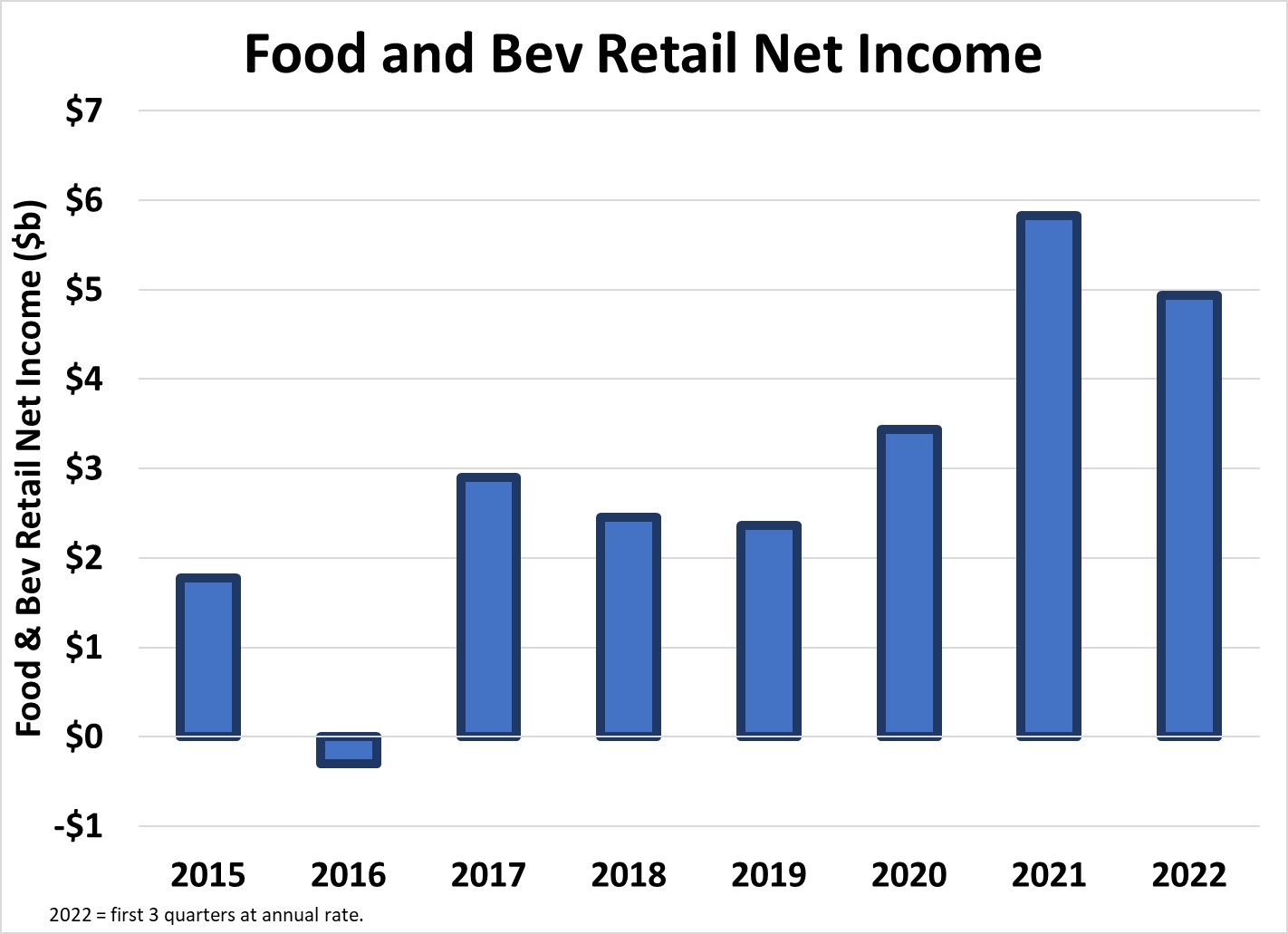

As shown in this graph, the MASS of profits in food retail has more than doubled since pre-COVID levels (as discussed in our new Centre for Future Work report): from $2.4 billion in 2019 to $5.2 billion over the latest 12 months (and a projected $5 billion for 2022, based on first three quarters data).

2. EVEN IF the sales margin had not increased, if the only reason revenues were growing was pure inflation in input costs, then even a CONSTANT margin would amount to supermarkets increasing their profits through pure inflation. Investors make investments based on return on equity, not sales margins. A constant sales margin on an inflating revenue base definitely translates into increased profits. (That’s why real estate agents became millionaires during the housing bubble, even though their ‘margin’ didn’t change.)

Consider this simple example. A grocery store’s expense statement, simplified, includes:

• Cost of merchandise/inventory, by far the biggest cost (let’s say $90 million)

• Operating, overhead and labour (let’s say $10 million)

Let’s assume a 2% sales margin on top of costs; total revenue then equals $102 million.

Now, if all purchased inputs grow in cost by 10%, and grocers simply pass on a 10% increase in final prices (as per the narrative promoted by the supermarkets), what happens?

• Merchandise: $99 million (up 10%)

• Other costs: $10 million

• Revenue: $112.2 million (up 10%)

• Profit = $3.2 million (2.85% margin, that’s higher).

Even if the supermarkets’ direct operating costs increased by 10% as well (and it’s not clear why they would, as a result of the supply chain issues that have bedeviled agricultural markets reently), you still get a higher mass of profit and a higher rate of profit (relative to invested capital, which hasn’t changed as a result of any of this) thanks to higher costs and a proportional increase in prices:

• Merchandise: still $99 million

• Other costs: $11 million (now also up 10%)

• Revenue: still $112.2 million

• Profit = now $2.2 million. That’s still 2% of total revenue, so the margin hasn’t changed – but profit is higher in absolute terms and also as a ratio to invested capital (which is what investors look for).

Even in this scenario, the most generous one possible for the supermarkets, the companies have increased both the mass and rate of profit by one-tenth, for doing nothing other than ‘passing along’ higher costs (and then some!) to consumers. So the argument that a constant margin means they haven’t profited from inflation isn’t valid. (More important, the margin HAS increased.)

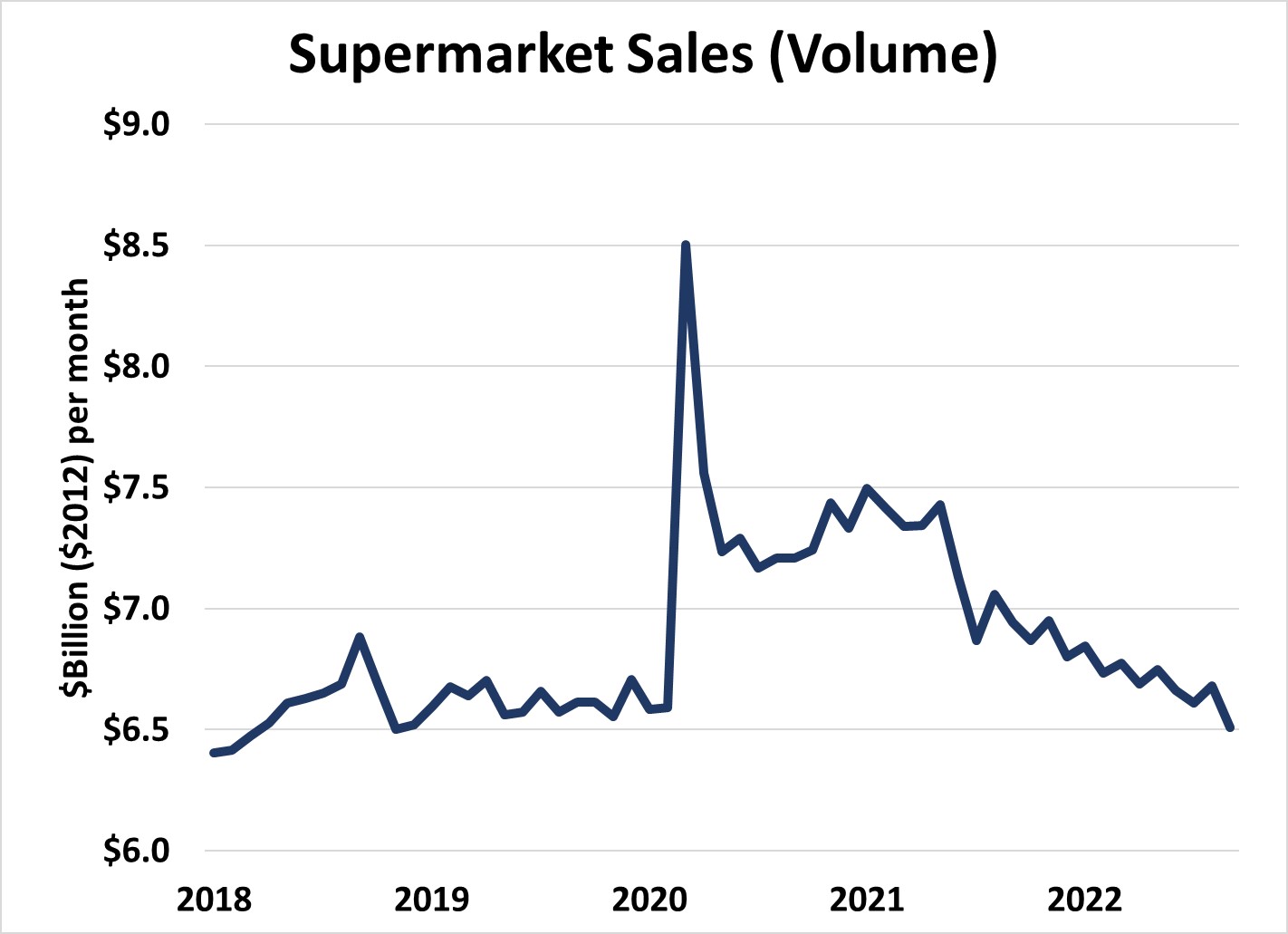

3. The above example assumes the only thing that’s changed is the nominal value of a given amount of physical sales. If revenue growth was due to a greater volume of actual business, then it would be reasonable for supermarkets to generate higher profits (and in that case they would have had to increase investment in stores, equipment, etc. in order to supply that growing volume – so the final impact on return on equity might be a wash). But in fact, the OPPOSITE is true: the physical volume of business flowing through the supermarkets has been FALLING, not growing. There was an enormous temporary spike in sales during the lockdowns (panic buying), mostly reversed by mid-2020. Then, more recently, the quantity of sales has steadily shrunk: in part because people could eat out again, but also because Canadians have responded to record food inflation with reduced quantities of purchases (and also substitution to cheaper products).

The volume of sales in supermarkets is now lower than it was before the pandemic hit – which is unusual given population growth since then. So the MARGIN of profits, and the MASS of profits, and the RATE of profits have all increased – but all generated from a SMALLER volume of actual physical business. That is definitely proof that the industry is profiting unusually from the current conjuncture of supply chain disruptions, inflation, and consumer desperation.

4. Finally, if in fact the problem was all driven by supply shocks that supermarkets have merely been forced to ‘pass on’ to consumers, there should have been a REDUCTON in profits (however measured: margin, mass, rate), not mere constancy in margins (which in fact increased). An inward shift of the supply curve in any normal commodity market should lead to reduced volume, increased price, and reduced profit (or ‘producer surplus’). The special case in which that wouldn’t occur, allowing profits to be perfectly protected, is under perfectly inelastic consumer demand (a vertical demand curve). In this special case, quantity and profit do not change, the price rises fully in response to the shift in supply, and consumers bear ALL the impact of the supply shock (producers bear none). That is not a valid depiction of the real grocery industry: to be sure, food demand is relatively inelastic (in that any given increase in price leads to less-than-proportionate decline in demand), but it is not PERFECTLY inelastic (as proven by the above data confirming the shrinking volume of grocery sales in Canada). In this regard, even MAINTAINING a given profit, let alone increasing it, would be unusual if the source of the problem was solely higher input costs.

Can we blame the problem of food price inflation on greed? Yes and no. Greed existed before COVID came along. But the combination of greed (more politely termed “profit maximization”), along with supply chain disruptions and consumer desperation during and after the pandemic, along with oligopolistic pricing power, clearly explains much of the pattern of recent inflation in Canada (especially for the essential commodities that have been the biggest drivers of inflation: energy, housing, and food). To claim that supermarkets and other firms are innocent conduits, merely passing on higher costs, is not empirically valid. As discussed in our recent Centre for Future Work paper, supermarkets are not the worst example of profiting from inflation (the energy industry is, far and away). But supermarkets have clearly profited from the post-pandemic inflation, and richly deserve the critical attention they are receiving.

In sum, the hard numbers clearly contradict the claim that supermarket profit margins are stable and no extra profits have been earned.