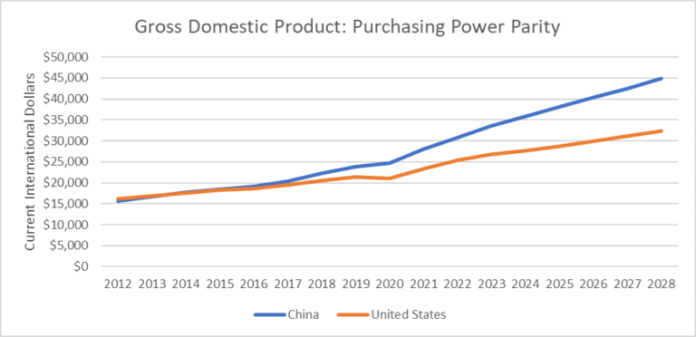

From Dean Baker It is standard for politicians, reporters, and columnists to refer to the United States as the world’s largest economy and China as the second largest. I suppose this assertion is good for these people’s egos, but it happens not to be true. Measuring by purchasing power parity, China’s economy passed the U.S. in 2014, and it is now roughly 25 percent larger.[1] The I.M.F. projects that China’s economy will be nearly 40 percent larger by 2028, the last year in its projections. Source: International Monetary Fund. The measure that the America boosters use is an exchange rate measure, which takes each country’s GDP in its own currency and then converts the currency into dollars at the current exchange rate. By this measure, the U.S. economy is still more than one-third

Topics:

Dean Baker considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Dean Baker

It is standard for politicians, reporters, and columnists to refer to the United States as the world’s largest economy and China as the second largest. I suppose this assertion is good for these people’s egos, but it happens not to be true. Measuring by purchasing power parity, China’s economy passed the U.S. in 2014, and it is now roughly 25 percent larger.[1] The I.M.F. projects that China’s economy will be nearly 40 percent larger by 2028, the last year in its projections.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

The measure that the America boosters use is an exchange rate measure, which takes each country’s GDP in its own currency and then converts the currency into dollars at the current exchange rate. By this measure, the U.S. economy is still more than one-third larger than China’s economy.

Economists usually prefer the purchasing power parity measure for most purposes. The exchange rate measure fluctuates hugely, as exchange rates can easily change 10 or 15 percent in a year. Exchange rates also can be somewhat arbitrary, as they are affected by countries’ decisions to try to control the value of their currency in international money markets.

By contrast, the purchasing power parity measure applies a common set of prices to all the items a country produces in a year. In effect, this means assuming that a car, a television set, a college education, etc. cost the same in every country. Applying common prices is a difficult task, goods and services vary substantially across countries, which is makes it hard to apply a single price. As a result, purchasing power parity measures clearly have a large degree of imprecision.

Nonetheless, it is clear that this is the measure that we are more interested for most purposes. If we want to know the quantity of goods and services a country produces in a year, we need to use the same set of prices. By this measure, there is no doubt that China’s economy is both considerably larger than the U.S. economy and growing far more rapidly.

Just to be clear, this doesn’t mean the Chinese people are on average richer than people in the United States. China has nearly four times the population, so on a per person basis, the U.S. is still more than three times as rich as China. But, it should not be a shock to us that a country with more than 1.4 billion people would have a larger economy than a country with 330 million.

For the folks who need more convincing, we can make comparisons of various items. We can start with auto production, a standard metric of manufacturing output. Last year, China produced more than 27.0 million cars, the United States produced a bit less than 10.1 million. (China also leads the world by far in the production and use of electric cars.) The cars made in the United States undoubtedly were better on average, but they would have to be an awful lot better to make up this gap.

To take a more old-fashioned measure, China produced over 1,030 million metric tons of steel in 2021. The United States produced less than 90 million metric tons.

China generated 8,540,000 gigawatt hours of electricity in 2021, nearly twice the 4,380,000 gigawatt hours generated in the United States. The gap is even larger if we look at solar and wind energy production. China has 307,000 megawatt hours of installed solar capacity, compared to 97,000 in the United States. China has 366,000 megawatt hours of installed wind capacity versus 141,000 in the United States.

We can look to some more modern measures. China has 1,050 million Internet users. The United States has 311 million. China has 975 million smartphone users, the United States has 276 million. In 2016 China graduated 4.7 million students with STEM degrees. In the U.S. the number was 330,000 for the same year. The definitions for STEM degrees are not the same, so the numbers are not strictly comparable, but it would be difficult to make the case that U.S. number is somehow larger. And the figure has almost certainly moved more in China’s favor over the last seven year.

In terms of impact on the world economy, China accounted for 14.7 percent of goods exports in 2020. The United States accounted for 8.1 percent. In the first nine months of last year, China was responsible for $90 billion in foreign direct investment. This compares to $66 billion for the United States.

We can pile on more statistics, but in category after category, China outpaces the United States, and often by a very large margin. If people want to put on their MAGA hats and insist the U.S. is still the world’s largest economy, they are welcome to do so, but Donald Trump lost the 2020 election and China’s economy is bigger.

Size Matters

The issue here is not just a question of bragging rights. China is clearly an international competitor, economically, militarily, and diplomatically. Many people want to take a confrontational approach to China, with the idea that we can isolate the country and spend it into the ground militarily, as we arguably did with the Soviet Union.

At its peak, the Soviet economy was roughly 60 percent of the size of the U.S. economy, China’s economy is already 25 percent larger. And, this gap is expanding rapidly. China is also far more integrated with the world economy than the Soviet Union ever was. This makes the prospect of isolating China far more difficult.

As a practical matter, it doesn’t matter whether we like China or not. It is here and it is not about to go away. We will need to find ways to deal with China that do not lead to military conflict.

Ideally, we would find areas where we could cooperate, for example sharing technology to address climate change and dealing with pandemics and other health threats. But, if anyone wants to push the New Cold War route, they should at least be aware of the numbers. This would not be your grandfather’s Cold War.

[1] I have included both Hong Kong and Macao in this calculation, since both are now effectively part of China.