Interesting article about local communities beginning to sue energy companies because of climate change and the mischaracterization of how oil products impact the nations climate. Down in Phoenix, we are seeing temperatures approaching the one hundred and teens. No relief is in sight for a couple of weeks. The same can be said for other parts of the country. The intriguing part is how the industry and advertisers are going about with messaging of their impact on the environment to the news media to get their point across. They are taking more of an aggressive stance. Anyway, hope you enjoy the read. Enabling Fossil Fuel Addiction: It’s About More Than Money, drilled.media A new climate case was filed this week. Multnomah County, the

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Advertsing, climate change, Oil, politics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Interesting article about local communities beginning to sue energy companies because of climate change and the mischaracterization of how oil products impact the nations climate. Down in Phoenix, we are seeing temperatures approaching the one hundred and teens. No relief is in sight for a couple of weeks. The same can be said for other parts of the country.

The intriguing part is how the industry and advertisers are going about with messaging of their impact on the environment to the news media to get their point across. They are taking more of an aggressive stance. Anyway, hope you enjoy the read.

Enabling Fossil Fuel Addiction: It’s About More Than Money, drilled.media

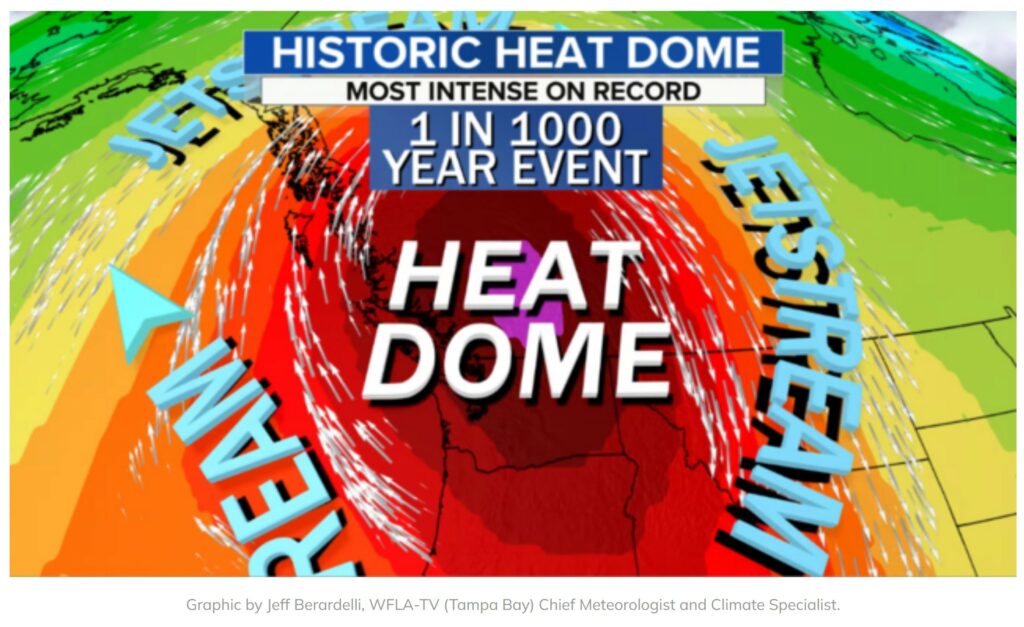

A new climate case was filed this week. Multnomah County, the Oregon county that includes Portland, filed suit against several oil majors for their role in exacerbating the climate change that led to the county’s “heat dome” in June 2021, which killed 69 people. But the case doesn’t just place blame at the feet of the oil and gas companies, it also includes trade groups such as the American Petroleum Institute and the Western States Petroleum Association. It includes refiners and distributors such as Koch Industries. This time, the industry’s favorite consulting firm, McKinsey & Company was added.

“Since 2010, McKinsey has worked for at least forty-three of the hundred companies that have pumped substantial tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere since 1965.” The complaint reads.

“Chevron is one of McKinsey’s biggest clients, generating at least $50 million in consulting fees in 2019. Saudi Aramco, number one on the list, has been a McKinsey client since at least the 1970s.”

But McKinsey isn’t a co-defendant here simply because it had fossil fuel clients.

“McKinsey has coordinated and participated in a deliberate misinformation campaign to downplay and/or outright deny the causal relationship between the GHG emissions of its members and extreme weather events like that those described herein,”

and the complaint argues.

“McKinsey’s deception is a substantial factor and cause of enormous harm to the Plaintiff for which this Defendant is individually and jointly and severally liable to Plaintiff.”

In fact, more than 1,000 of McKinsey’s own employees are not pleased with the firm’s role in perpetuating delayed action on climate. In 2021, they signed onto an open letter to McKinsey’s top partners, urging them to disclose their clients’ carbon emissions. Still, being pressured by your employees to embrace climate disclosure is another thing entirely from being hauled into court. The Multnomah County case marks the first time that one of what we might call the “fossil fuel enablers” has been named as a defendant in one of these cases. Enablers are firms that are not directly tied to the fossil fuel industry, but help to establish social license, finance projects, or shape policy on the industry’s behalf. It’s feasible that PR and ad agencies, banks, insurers, and other consulting firms could find themselves co-defendants with their Big Oil clients too.

Which has me thinking a lot about what prompted these folks to go so hard on fossil fuel’s behalf in the first place. Money, yes! $50 million is a lot of money. And yet . . . it represents only about half a percent of McKinsey’s annual $10.5 billion haul. The same holds true in the PR and ad space, where oil majors’ budgets are positively dwarfed by much more climate-friendly clients like Unilever or IKEA (which, yes, I know, also have their problems). When you look at ad spend with media outlets, too, fossil fuel dollars are not the pot of gold the public assumes them to be. In recent months I’ve spoken with loads of people about why the media, particularly legacy media, still has so many bad habits when it comes to covering climate. In every single case the assumption was that outlets must be compromised by the copious amounts of oil money they’re swimming in. Except . . . they’re not. Not even close.

The answer, I’m afraid, has much more to do with ideology, social license, and some deeply entrenched ideas that the industry has been pushing for a century or more. On the media front, it largely boils down to bullying. And the fragile egos of most people who work in media, which makes them/us ideal targets for bullying. Back in the early 1970s, the fossil fuel industry made a concerted effort to change not only its relationship with the media, but how the media worked in general. Spearheaded by Herb Schmertz at Mobil but quickly mimicked by every other oil flak, the strategy was something Schmertz called “creative confrontation.”

In his handbook for corporate PR, Goodbye to the Low Profile, Schmertz tells his colleagues the time for cozying up to journalists, or giving them access and information and taking them to lunch, the approach favored by early PR leaders like Ivy Lee is over, particularly for industries or companies finding themselves on the receiving end of public criticism. The subtitle of the book is “The art of creative confrontation,” by which Schmertz means effective bullying.

“I realize that most people think that confrontation is something to be avoided at all costs, but I disagree,” he wrote. “Confrontation doesn’t have to be abrasive or rude or unpleasant, it can just as easily be polite and good-humored. But you can’t win your battles by running away from them. You have to get out there and meet your critics head-on.”

What that looked like in practice for Schmertz was regularly calling up editors and journalists and letting them have it, writing op-eds and letters to the editor about media coverage he found to be “biased” against Mobil, using Mobil’s weekly advertorial spot in The New York Times to rant about it, pulling ad buys from outlets that wouldn’t play ball (like The Wall Street Journal, which was a very different paper back then), and cutting non-compliant journalists and editors off from speaking to Mobil staff or accessing even basic information like quarterly earnings reports and press releases. Schmertz was a regular on nightly news programs and talk radio as well, where he regularly berated the press for either its total lack of understanding of the oil industry or bias against corporate America in general. Practices he painted as biased against Mobil, and the broader fossil fuel industry, included the use of leaked documents and whistleblowers, and undercover journalism, the latter of which is almost unheard of in the U.S. today thanks to a litany of expensive lawsuits against newsrooms that once engaged in the practice routinely. In a 1980s special on 60 Minutes evaluating the media’s performance in covering corporate America (an idea pushed by Schmertz in the first place), a handful of CEOs plus Schmertz square off against a panel of journalists that included Mike Wallace. Schmertz and the CEOs accused Wallace and co of engaging in “yellow journalism” and muckraking, of being more interested in capturing gotcha moments on film than informing the public, of being so addicted to controversy that they were failing the public.

“You will come into somebody’s office having interviewed all of the other people and gotten your material and then dump a very complex and difficult situation and question on an unprepared interviewee,” Schmertz complained.

Um, yeah, that’s called journalism, Herb. But the panel engaged with this as a legitimate gripe and nodded along as Schmertz argued that an informed, prepared interviewee would more effectively inform the public. Schmertz pulled this kind of stuff for decades, and while initially the press rolled their eyes or laughed him off, in many cases they also heard him out. That 60 Minutes panel wasn’t the only time a mainstream national news show asked Schmertz to play the role of media critic. In 1981, Ted Koppel devoted an episode of his nightly news show to letting Schmertz air his grievances.

Four years later, Koppel had Schmertz on Nightline for an episode about press freedom and SLAPP suits and whether corporations were filing defamation suits too liberally against the press; Schmertz’s answer, naturally, was no. His counterpart on the show was an actual media critic for The New York Times at the time, Anthony Lewis. Because the VP of a major oil company is an equal counterpart to the New York Times media columnist on questions of press freedom. Schmertz argued time and again that yes, he and other Mobil execs were just like any other expert source and should be treated the same. And mainstream media outlets increasingly began to line up behind that idea.

Over time they also shifted how they covered not only Mobil, but also the oil industry in general. Fast forward to today and it’s not uncommon to hear a staffer at a major national publication say they need to stay on the good side of PR folks working for the industry lest they lose access, or that this or that spokesperson at an activist organization is biased but the head of the American Petroleum Institute is a legitimate expert source on the industry. Has the media been compromised by millions of fossil fuel ad dollars? Sure. But it’s been far more compromised by a long-running influence campaign that often incorporated litigation or threats thereof.

For the PR and ad folks, both within media organizations and at global agencies, it’s less about influence or money and more about ideology. The idea that oil companies represent the pinnacle of corporate America, for example. Take a look at this blog post Richard Edelman, head of Edelman PR, wrote when the company was moving out of its former HQ in Chicago. As he waxed nostalgic about the firm’s office in the Aon Center, Edelman wrote out a list of his favorite recollections of the place. Number one: “Dan [Richard’s father, the founder of the firm] Loved the Building—He was so proud that his company was in the same building as giant Standard Oil of Indiana.”

Edelman’s predecessors in the industry did such a phenomenal job of wrapping oil companies in American identity and capitalism that the connection is still remarkably strong today. Even as the PR industry comes under fire for peddling greenwashing, there’s still something about handling an oil company account that feels prestigious. Like you’ve made it. Every agency needs a tobacco client, a car company, an airline and an oil company, right? The industry’s executives are living in a time warp. Back in the 1990s, Richard convinced his father Dan it was no longer ethical to work with tobacco companies (or so says the biography of Dan that the PR firm commissioned). Now who will convince Richard the same time has come for fossil fuels?

For the agency execs that don’t still think of fossil fuel giants as great American companies, there’s the “slippery slope” argument: If you stop working for fossil fuel clients, what about cars? Or airlines? Every industry generates greenhouse gas emissions, where do you draw the line?

The Guardian actually answered this question very tidily when it moved to stop taking fossil fuel ads back in 2020. CEO Anna Bateson explained the clear difference between fossil fuel ads and everyone else’s: they weren’t advertising a product. All the oil and gas ads being presented to The Guardian were reputational ads for the companies, or greenwashing/pinkwashing/brownwashing/rainbowwashing ads about various corporate initiatives. It was a relatively easy line to draw.

Then of course lots of enablers convince themselves that they are actually helping the industry transition. That they are encouraging and amplifying the good stuff. But that ignores the role work plays in making the public think the industry is more committed to change than it actually is. The fact remains that no fossil fuel company spends more than 5% of its capital on anything other than hydrocarbons; and in most cases they’re reducing that amount and ramping up fossil fuel production at the moment. Meanwhile they spend a fortune on PR, lobbying, strategy, all the tools necessary to delay or block climate action and, importantly, they couldn’t do it without those tools.

“The largest Fossil Fuel Defendants worked with McKinsey to create strategies that allowed for exponential increase in the use of their products, artificial creation of energy dependence, and control climate messaging to create doubt,” the Multnomah County complaint reads. It goes on to argue that in so doing, the fossil fuel and coal defendants, “jointly through the Trade Group Defendants and Other Defendants (McKinsey) engaged in fraud, deceit, or intentional misrepresentation.”

It’s a watershed moment that makes it clear the enablers that have allowed themselves to be bought, bullied, or brainwashed by this industry won’t escape accountability.