By Laura B. Attanasio and Kimberley H. Geissler Health Affairs This article is the latest in the Health Affairs Forefront series, Accountable Care for Population Health, featuring analysis and discussion of how to understand, design, support, and measure patient-centered, cost-efficient care under the umbrella of accountable care. ~~~~~~~~ The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate of any industrialized country, and it has increased in recent years. Other more common negative maternal health outcomes such as severe maternal morbidity are also on the rise. Improving the quality of perinatal care to address these poor maternal health outcomes is a pressing policy concern. More than 40 percent of births in the US each year

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Healthcare, Maternal Healthcare, politics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

by Laura B. Attanasio and Kimberley H. Geissler

Health Affairs

This article is the latest in the Health Affairs Forefront series, Accountable Care for Population Health, featuring analysis and discussion of how to understand, design, support, and measure patient-centered, cost-efficient care under the umbrella of accountable care.

~~~~~~~~

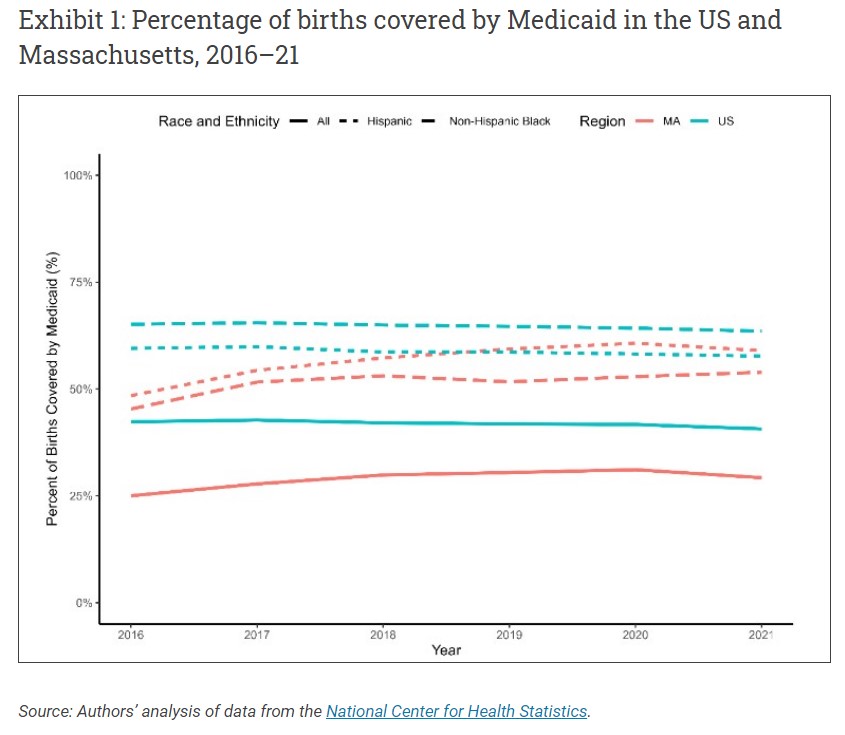

The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate of any industrialized country, and it has increased in recent years. Other more common negative maternal health outcomes such as severe maternal morbidity are also on the rise. Improving the quality of perinatal care to address these poor maternal health outcomes is a pressing policy concern. More than 40 percent of births in the US each year are covered by Medicaid (exhibit 1), including 64 percent of births to Black birthing people, making changes to federal Medicaid policy or state Medicaid programs potential policy levers for addressing maternal health and maternal health equity.

Many state Medicaid programs have been experimenting with financing and delivery system reforms that may have implications for perinatal health care. In particular, a number of states have implemented accountable care organizations (ACOs) in their Medicaid programs. In ACOs, a group of clinicians—generally primary care clinicians—provides care for a specified set of patients and has responsibility for the quality and cost of care for those patients. This arrangement is intended to incentivize higher-quality care while reducing costs. ACOs aim to improve care quality by improving coordination in patient care and emphasizing appropriate primary care to avoid potentially preventable and costly emergency department visits and inpatient hospitalizations. ACOs were launched in Medicare following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, and research has found that Medicare ACOs can have positive effects on quality and may moderately lower costs. Research on the effects of Medicaid ACOs broadly, while limited, has found some evidence of improved quality and lower costs.

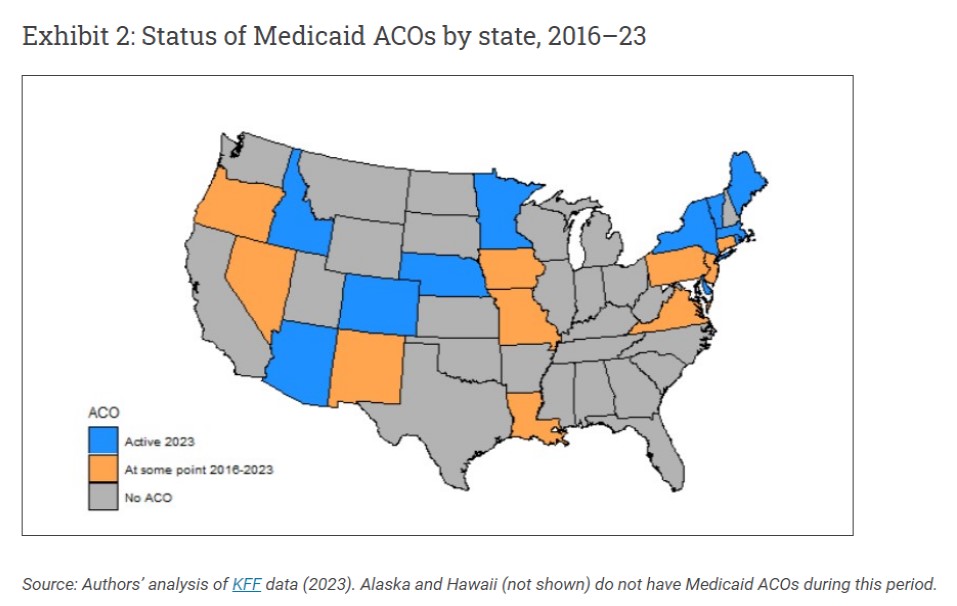

Between 2016 and 2023, 21 states had Medicaid ACOs at some point, and 10 states had active Medicaid ACOs in 2023 (exhibit 2). The focus of ACOs on improved care coordination and appropriate use of primary care could be beneficial in the perinatal period. Additionally, some state Medicaid programs are increasing their focus on addressing health-related social needs, both through Medicaid ACOs and otherwise. Research assessing the impacts of Medicaid ACOs on birth outcomes for infants has had mixed findings, with some studies findings improved outcomes following Medicaid ACO implementation and others finding no effect. Medicaid ACO implementation in Oregon was associated with increased prenatal care use and reductions in disparities in prenatal care use between birthing people with Medicaid and birthing people with private insurance. Across three states, Medicaid ACO implementation was associated with reductions in cesarean rates and reduced costs per birth, but was not associated with changes in severe maternal morbidity during the birth hospitalization. Despite the large proportion of the birthing population covered by Medicaid, the impact of Medicaid ACOs on a broader set of maternal health outcomes across the perinatal period has not been examined.

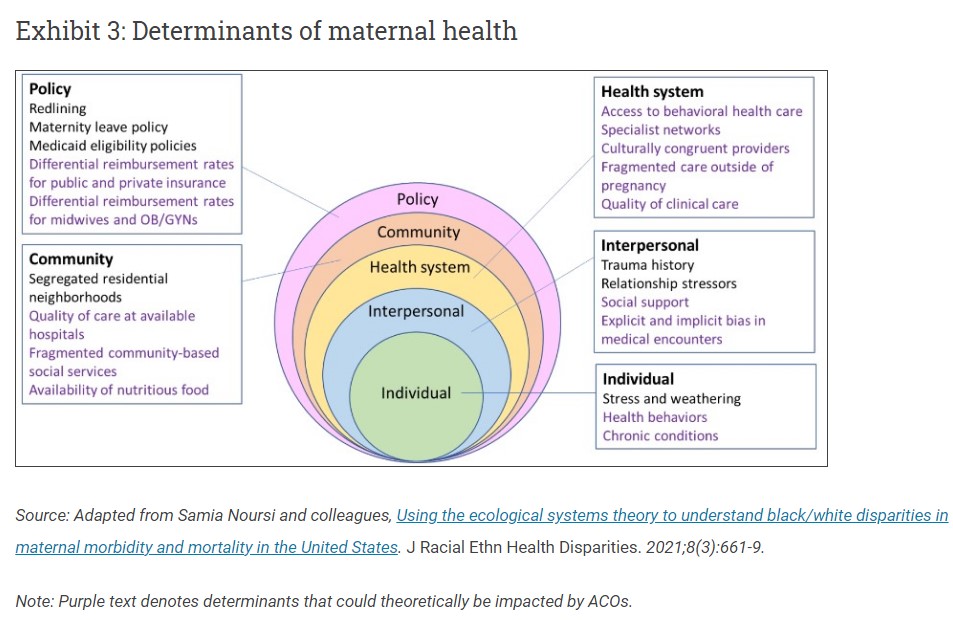

Determinants of maternal health include a complex interplay of factors at multiple levels and domains of influence (exhibit 3). Theoretically, a number of these factors (depicted in purple text) could be impacted by implementation of Medicaid ACOs, although some may be more readily addressable by ACOs than others. Medicaid ACOs in Massachusetts were established under a Section 1115 waiver demonstration project (2017–23), with most Massachusetts Medicaid enrollees shifted into ACOs beginning in March 2018.

Medicaid ACO Impacts On Maternal Health And Maternal Health Equity

Using document review, reports of relevant research, and interviews with key informants from the Massachusetts Medicaid ACOs including individuals in ACO management and maternity care clinicians, we identify the role of Massachusetts Medicaid ACOs in maternal health and maternal health equity. Here, we present high-level interpretation of findings from those sources and make recommendations for other states.

Medicaid ACOs may have substantial scope for improving maternal health outcomes, but the structure and implementation of the ACOs is critical. Most directly, Medicaid ACOs may be able to impact quality and coordination of care by influencing maternity care delivered prenatally or during the birth hospitalization, connecting patients being seen by a maternity care clinician to behavioral health care if needed, and connecting patients back to primary care postpartum. Medicaid ACOs can also potentially impact community-level determinants of maternal health by screening for health-related social needs and creating smoother connections to community-based social services, or directly providing or reimbursing for other enhanced services that are not typically included in perinatal care or covered by Medicaid.

However, the initial demonstration waiver that created Medicaid ACOs in Massachusetts did not explicitly address the population of birthing people in its goals, and key informant interviews revealed that maternal health was not an initial focus of ACO initiatives. ACO participants reported that during the early implementation period, efforts were largely focused on setting up their programs and meeting requirements, although some ACOs did lay the groundwork for greater consideration of maternal health as their organizations matured.

Policy-Level Determinants of Maternal Health

Depending on the structure of the Medicaid ACOs and state policies, ACOs may have wide latitude in selecting how many and which specialists (including OB/GYNs and midwives) to include, reimbursement rates, and other policy and organizational factors. Massachusetts Medicaid ACOs varied widely in their inclusion of OB/GYNs, midwives, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists. Coverage of doula services, which provide non-medical support during the perinatal period, was not required under the initial waiver and was not covered by most Medicaid ACOs during that time. While not specific to ACO members, Medicaid coverage of doula services is required in the Massachusetts section 1115 waiver extension (2023–28) and went into effect as of December 2023.

Community-Level Determinants Of Maternal Health

In the initial implementation period, Massachusetts Medicaid ACOs were required to screen annually for health-related social needs, and ACOs received funding to address health-related social needs including housing stabilization and support and nutrition through community partners. These programs, although not specific to the birthing population, were often available to people during pregnancy. Some ACOs implemented care management programs that were available to all members, including those who were pregnant, who had been identified as having additional health-related social needs. Other services addressing community-level determinants may have been available to particular subsets of the birthing population. For example, at least one ACO was preparing to launch a nutrition program for individuals with gestational diabetes as part of a broader diabetes nutrition program

Health System Determinants Of Maternal Health

Implemented as a joint financing and delivery system reform, one might expect the health system to be the level most impacted by Medicaid ACOs. However, the primary care orientation of the Massachusetts Medicaid ACOs may make it challenging structurally to impact care for birthing people. In the Massachusetts Medicaid ACO program, enrollees are attributed to a single primary care provider for the purposes of calculating quality metrics and distributing shared savings and losses, and primary care providers may only contract with one MassHealth ACO. Clinicians who provide most maternity care, OB/GYNs and certified nurse-midwives, are not designated as primary care providers within ACOs. This means that they are potentially in the specialist networks of multiple ACOs and providing care to patients from multiple ACOs; thus, these maternity care clinicians are generally insulated from the incentive structure that ACOs are meant to create. Given that maternity care clinicians typically provide most care during pregnancy and in the first months postpartum, it may be challenging for ACOs to impact clinical care provided in perinatal care or hospital obstetric care if maternity care clinicians are not more integrated into ACOs.

ACOs could facilitate timely initiation of prenatal care, which was included as a Massachusetts Medicaid ACO quality metric in the initial demonstration waiver phase and was the only quality metric directly relevant to maternal health. Some interview participants noted that it was easy to identify new ACO members who are pregnant through the enrollment process when other health needs screenings were taking place; however, identifying existing members who become pregnant and facilitating early entry into prenatal care may be more challenging, particularly if the member does not reach out to primary care when they discover they are pregnant. Increasing timely initiation of prenatal care is important for health equity as there are well-documented disparities in accessing prenatal care in the first trimester by race and ethnicity and by indicators of socioeconomic status such as education.

A focus in the waiver on integrating physical and behavioral health services has the potential to improve access to services for birthing people with behavioral health needs, but the integration of behavioral health care into maternity care systems remained a barrier. Although some interview participants noted that patients who were pregnant or postpartum could have benefitted from the enhanced connections to behavioral health through primary care enabled by the new ACO structure, none of the interview participants were aware of behavioral health services being explicitly integrated into obstetric care as part of the Medicaid ACOs. Most interview participants reported ongoing challenges with patient access to mental health services during the perinatal period.

A Woman’s Right to Safe Healthcare Outcomes, Angry Bear 2019

Part 2 of Saving Rural Hospitals – Problems and Solutions for Rural Hospitals – Angry Bear 2023