Discussing US Debt looked interesting enough to post on Angry Bear. I do not agree with the proposed fixes as I believe there are other fixes which would resolve the issues mentioned. Perhaps you have better ideas? Addressing Rising US Debt by Karen Dynan Econofact, The Issue: United States Federal debt rose sharply after the Great Recession. At 98% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023, it is close to its highest level ever. Under current policy, the federal debt is expected to continue rising over the next three decades to reach levels well above any historical experience. It holds true even under optimistic assumptions about future economic conditions. To keep the federal debt from ballooning to the levels currently predicted,

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Debt, Econofact, law, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Discussing US Debt looked interesting enough to post on Angry Bear. I do not agree with the proposed fixes as I believe there are other fixes which would resolve the issues mentioned. Perhaps you have better ideas?

Addressing Rising US Debt

by Karen Dynan

Econofact,

The Issue:

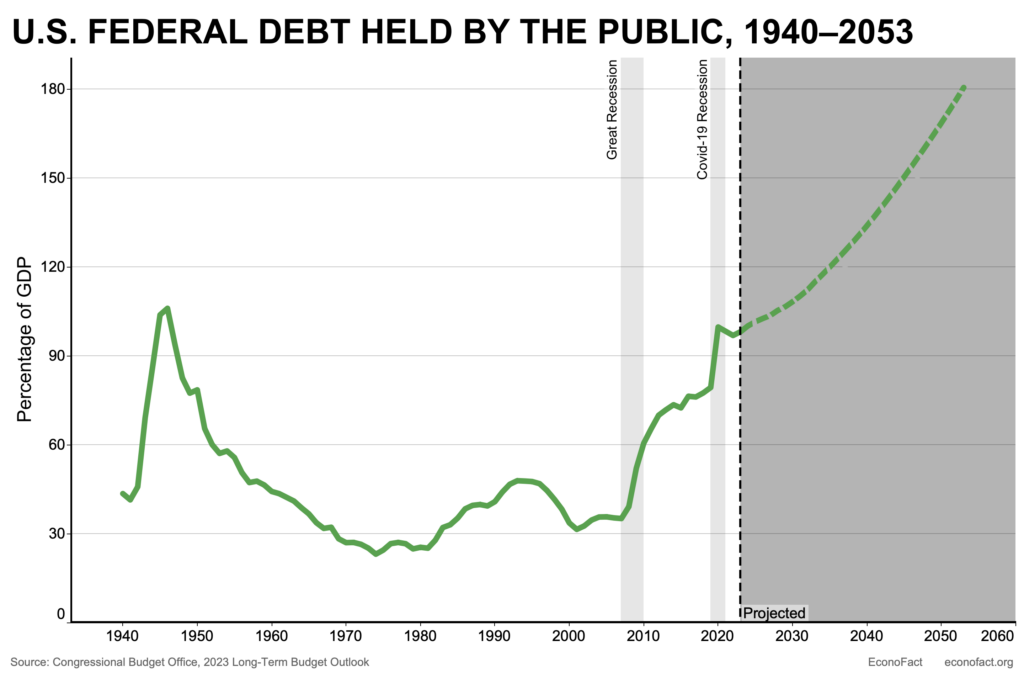

United States Federal debt rose sharply after the Great Recession. At 98% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023, it is close to its highest level ever. Under current policy, the federal debt is expected to continue rising over the next three decades to reach levels well above any historical experience. It holds true even under optimistic assumptions about future economic conditions. To keep the federal debt from ballooning to the levels currently predicted, a closer alignment of government spending and revenues needs to occur in coming years. Changes in policy substantially narrowing the federal deficit going forward may have economic and political disadvantages. Changes will be needed, as unprecedented levels of government debt impose significant economic costs and risks.

The Facts:

Negative economic shocks and policy changes over the past two decades have shifted current and projected levels of federal debt to higher levels.

The United States has seen two significant adverse shocks to economic activity in the 21st century. The deep and prolonged Great Recession beginning in 2007 as a result of the global US financial crisis and the sharp economic downturn that followed the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. These episodes led to drops in economic activity and lower tax revenues and, at the same time. Increases in federal spending on recovery programs contributed. A lasting downshift in government revenues brought about by major changes in tax policy still contributes to higher levels of debt. The changes in tax policy include the extension of tax cuts from early in the first decade of the 2000s and tax cuts enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. If the provisions of the 2017 tax cuts scheduled to expire in the next few years were to be extended, the projected path of tax revenues would shift further down. An increase between $400 billion and $500 billion per year in the late 2020s and early 2030s.

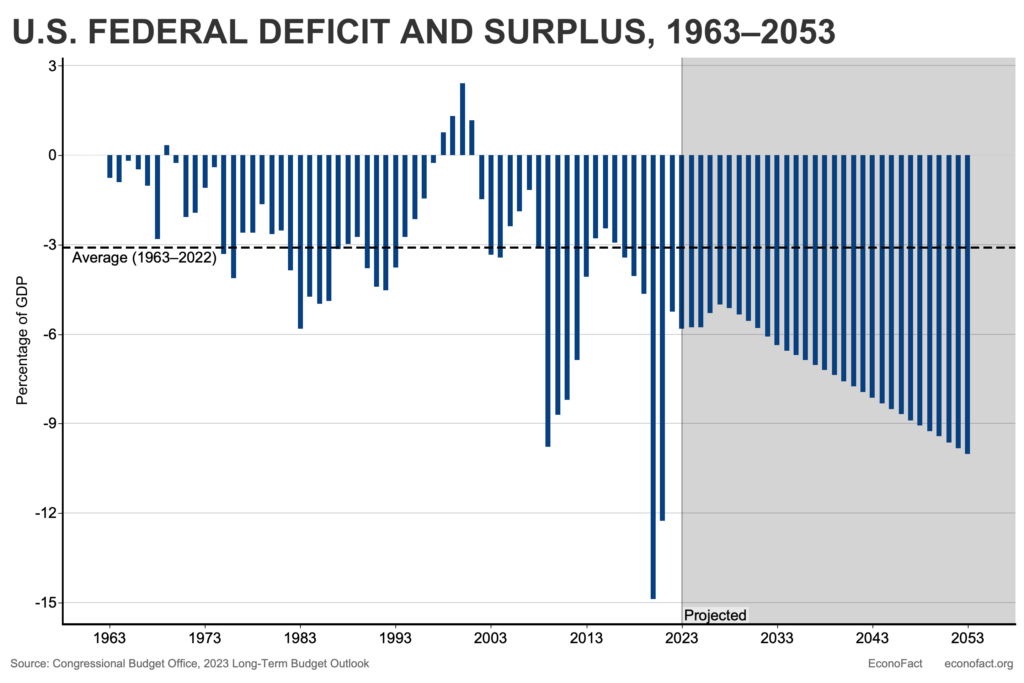

Behind the projected surge in US federal debt over the next three decades is an expected increase of the federal budget deficit, which is currently high and projected to rise steeply under existing law.

Briefly; federal budget deficit occurs when federal government spending exceeds its revenues. The government needs to borrow in order to make up the difference. The federal debt is the accumulation of federal budget deficits over time. It is not uncommon for the US federal government to have a budget deficit. Having deficits modest in size is sustainable given growth in the economy. However, the current size of the federal deficit, while smaller than its pandemic highs, is large by historical standards (chart below). Moreover, the budget deficit is projected to climb much higher over the next three decades, reaching 10% of GDP by 2053.

The aging US population is a key factor contributing to higher projected government spending.

The proportion of the US population aged 65 and older grew from about 12% in the first decade of the 2000s to 17% in 2023. Projections indicate a further increase to 22% by 2050. An increasing older population will require significant federal support for both income and health care (see here and here). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has projections using current policy. By 2053, the CBO projects Social Security outlays will rise by nearly 1% of GDP. It also projects spending on major federal healthcare programs, including Medicare, will rise by 3% of GDP. Spending on Social Security and federal health care programs will amount to 15% of GDP by 2053. This increase will drive the primary deficit (the deficit excluding interest payments on our existing debt) higher.

Ongoing large primary deficits, along with an already-high level of debt and interest costs, lead to a dramatic snowball effect over time.

A high level of accumulated debt and higher interest rates mean interest payments on our debt are an increasing part of federal spending. Ongoing large primary deficits generate additional debt leading to mounting interest costs. This in turn leads to an additional increase in the total deficit and debt. Under the assumption government borrowing rates remain at levels somewhat higher than the levels of the late 2010s, the CBO estimates that higher interest costs will push up the overall deficit by an additional 4% of GDP by 2053. Absent policy changes, this dynamic will push the deficit and debt ever higher even in the years beyond CBO’s window.

These structural challenges mean that even “good luck” with economic developments that would mitigate the debt burden, such as high productivity or low interest rates, will not put the debt on a sustainable path.

Growth Estimates of federal debt over time depend on assumptions about trends in productivity and interest rates and other factors. Higher-than-expected productivity growth leads to higher GDP growth, which in turn reduces the burden of higher debt. However, even under the most optimistic scenario for productivity growth estimated by the CBO, the federal debt would increase to 137% of GDP by 2053 or well above the historical range. The same is true for the most optimistic interest rate scenario considered by the CBO. An interest rate path that starts 5 basis points lower than baseline in 2023, with the gap then growing by 5 basis points per year, still results in the federal debt held by the public in 2053 increasing to 143 percent of GDP (see here). These analyses underscore that even favorable macroeconomic outcomes are very unlikely to change the conclusion that federal debt is on an unsustainable path.

The projected path of US federal debt presents significant economic costs and risks.

First, increased borrowing by the government crowds out borrowing by households and businesses. The competition for funds drives up interest rates, making it more expensive for individuals and businesses to borrow. As a result, private investment in productive capital decreases, leading to lower future output and national income. Second, elevated borrowing raises the risk of a fiscal crisis. If investors become reluctant to lend money to the government because they fear the debt will not be repaid, government borrowing rates can rise suddenly as prospective lenders demand more compensation to hold government debt. Finally, higher debt also comes with the costs of reduced “fiscal space,” meaning a limited capacity to increase the budget deficit, even temporarily, without endangering the access of a country’s government to financial markets or the sustainability of its debt. A lack of fiscal space constrains a country’s ability to effectively address sudden domestic needs, such as economic crises or pandemics, as well as international threats.

Many of the policy changes that could help put the debt on a sustainable path have disadvantages, so choices will need to be made carefully.

Many of our federal spending programs serve important purposes such as promoting economic growth, fostering economic mobility, mitigating hardship, and protecting national security. Large increases in taxes would not be popular, and some such changes could lead people to work less, save less, invest less, and innovate less.

What this Means:

The challenge posed by high and rising federal debt is significant but manageable as a matter of economics. For example, CBO projects that a combination of reductions in noninterest spending and increases in taxes that reduce the deficit by an average of 2.8% of GDP in coming decades would be expected to keep the ratio of debt to GDP at its current level; alternatively, reducing the deficit by an average of 3.3% of GDP over the 2027 to 2052 period (which would balance the primary deficit) would result in a gradual decline in the debt relative to GDP over time. Policymakers will need to carefully weigh the economic tradeoffs as they make the needed changes to spending and taxes. But the biggest obstacle to addressing high and rising federal debt may be political. Promises not to touch substantial key federal spending programs or to raise taxes are popular, but they cannot all be realized if we are to put the budget on a sustainable path.