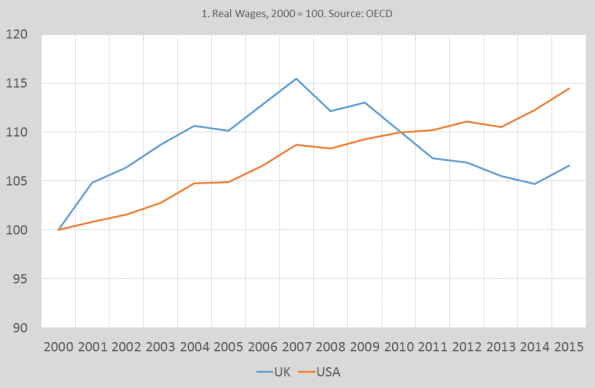

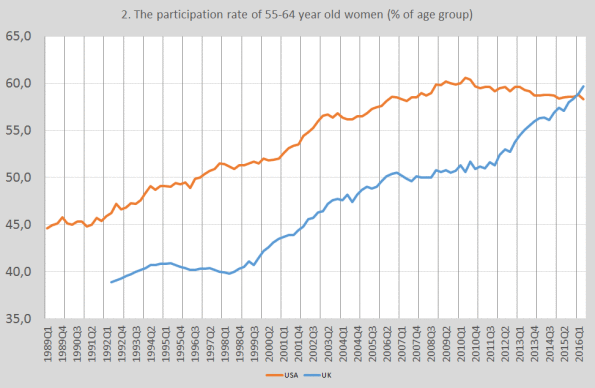

Are neoclassical macro models post-truth? It might very well be. The ‘workhorse’ neoclassical macro ‘DSGE’ models used by for instance central banks state that lower real wages will solve unemployment, largely because these lower wages will entice ‘marginal’ workers, like the elderly and women to leave the labor force (read this, by Lawrence Christiano, Mathias Trabandt and Karl Walentin (2011). Less workers, unemployment solved! But does this also happen? Ehhmmm…no (graph2). After 2008, real wages fell in the UK and increased in the USA. But contrary to the ideas embedded in the Cristiano e.a. model, the participation rates of, for instance, elderly women in the USA decreased. While the opposite happened in the UK… (the same held for the entire labor force, though in different degrees, but it seemed worthwhile to take a closer look at those ‘marginal’ workers). When one looks at a larger set of countries, using the OECD real wages data and the Eurostat participation data it shows that even in Greece, which knew a 20% decline of real wages, the participation rate (especially of women) still increased… Just like in Iceland, which witnessed a 15% increase of real wages. The economists writing down these models (or at least the European ones) have of course noticed such developments.

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Are neoclassical macro models post-truth? It might very well be. The ‘workhorse’ neoclassical macro ‘DSGE’ models used by for instance central banks state that lower real wages will solve unemployment, largely because these lower wages will entice ‘marginal’ workers, like the elderly and women to leave the labor force (read this, by Lawrence Christiano, Mathias Trabandt and Karl Walentin (2011). Less workers, unemployment solved! But does this also happen? Ehhmmm…no (graph2).

Are neoclassical macro models post-truth? It might very well be. The ‘workhorse’ neoclassical macro ‘DSGE’ models used by for instance central banks state that lower real wages will solve unemployment, largely because these lower wages will entice ‘marginal’ workers, like the elderly and women to leave the labor force (read this, by Lawrence Christiano, Mathias Trabandt and Karl Walentin (2011). Less workers, unemployment solved! But does this also happen? Ehhmmm…no (graph2).

After 2008, real wages fell in the UK and increased in the USA. But contrary to the ideas embedded in the Cristiano e.a. model, the participation rates of, for instance, elderly women in the USA decreased. While the opposite happened in the UK… (the same held for the entire labor force, though in different degrees, but it seemed worthwhile to take a closer look at those ‘marginal’ workers). When one looks at a larger set of countries, using the OECD real wages data and the Eurostat participation data it shows that even in Greece, which knew a 20% decline of real wages, the participation rate (especially of women) still increased… Just like in Iceland, which witnessed a 15% increase of real wages.

The economists writing down these models (or at least the European ones) have of course noticed such developments. How do they try to explain these, using models which predict the opposite? To explain this, I have to say a little about these models. According to neoclassical macro, people do not like to work. Hence, they have to be paid to work. Lower pay will lead to a decline of the ‘participation rate’ or the percentage of people wanting a job (or the total amount of hours or the average amount of hours supplied by ‘the representative household’, the models do not entirely agree about the metric of choice). Consumption of these lazy dropouts won’t decrease, as the entire nation is one big happy household which takes loving care of its members, employed, unemployed and non-participating members alike. In this world, foreclosure does not exist!

Real life unemployment basically means that wages are too high (i.e: they did not decline enough) and too many people want a job (look here for a Banca d’Italia study by Fransesco Nucci and Mariana Riggi which tries to explain the difference between the EU and the USA. Look here for a 2016 working paper by Miguel Casares Miguel and Jesús Vázquez (2016), ‘Why are labor markets in Spain and Germany so different?’). Though there is what’s called ‘habit persistence’, too, or the idea that the unemployed, somewhat irrationally, are loath to diminish consumption when real wages go down (this is not entirely consistent with the idea that everybody is 100% consumption-insured, but whatever). In your and mine language: the rent (or your mortgage interest bill) has to be paid. This irrationality makes (members of ) households want to stay in the labor force… And there are of course ‘shocks’, like the doubling of the participation rate of women, everywhere (also in Turkey, albeit fourty years after the USA and thirty years after the EU). The answer of these economists to cope with such schocks: lower wages. As that will restrict the inflow of people into the labor market. And when people can’t pay their mortgage interest bill? Let them get lost. Let them drop out. And let them discover the truth: in the real world, foreclosure does exist. Just like involuntary unemployment. Might this all sound as a somewhat extreme, not to say juvenile rant? Look here for comparable ideas by Roger Farmer and here for comparable ideas from the Worhtwhile Canadian Initiative blog. Aside: TALA ( There Are Loads of Alternatives ): much less dogmatic, more comprehensive, subtle and more interesting (and non-neoclassical) study is: Casado, Jose Maria, Cristina Fernandez and Juan F. Jimeno (2015). ‘Worker flows in the European Union during the Great Recession’ ECB Working Paper Series 1862