From David Ruccio During the recent presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised to revitalize American manufacturing—and bring back “good” manufacturing jobs. So did Hillary Clinton. What neither candidate was willing to acknowledge is that, while manufacturing output was already on the rebound after the Great Recession, the jobs weren’t going to come back. As is clear from the chart above, manufacturing output has grown (by about 21 percent) since the end of the recession and is now nearing pre-recession levels (although still down from its pre-crash level by about 5 percent). But employment in the manufacturing sector is only up a small amount (8 percent) since its post-crash low and is still lower, by about 1.5 million jobs (or 11 percent), than in December 2007. So, even if manufacturing production continues to grow, manufacturing jobs won’t (at least at the same rate). That’s because productivity in manufacturing continues to increase—as employers decide to change work rules, reorganize the factories, and introduce robotics and other forms of automation. Manufacturing workers, in other words, are being forced to produce more with less. That trend—of employment not matching the growth in output—just represents a longer term tendency in American manufacturing.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

During the recent presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised to revitalize American manufacturing—and bring back “good” manufacturing jobs. So did Hillary Clinton.

What neither candidate was willing to acknowledge is that, while manufacturing output was already on the rebound after the Great Recession, the jobs weren’t going to come back.

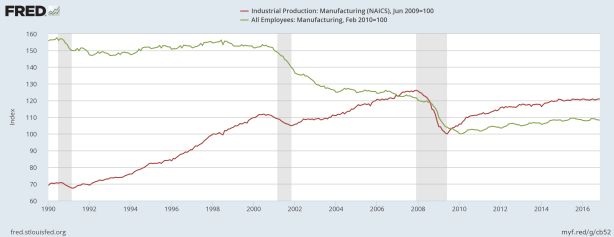

As is clear from the chart above, manufacturing output has grown (by about 21 percent) since the end of the recession and is now nearing pre-recession levels (although still down from its pre-crash level by about 5 percent). But employment in the manufacturing sector is only up a small amount (8 percent) since its post-crash low and is still lower, by about 1.5 million jobs (or 11 percent), than in December 2007.

So, even if manufacturing production continues to grow, manufacturing jobs won’t (at least at the same rate). That’s because productivity in manufacturing continues to increase—as employers decide to change work rules, reorganize the factories, and introduce robotics and other forms of automation. Manufacturing workers, in other words, are being forced to produce more with less.

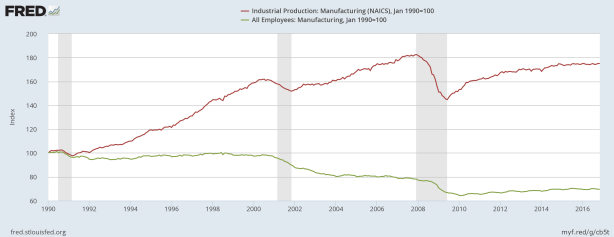

That trend—of employment not matching the growth in output—just represents a longer term tendency in American manufacturing. If we start back in 1990 (as in the chart above, indexed to January 1990), output has increased 75 percent while employment has actually fallen by more than 30 percent.

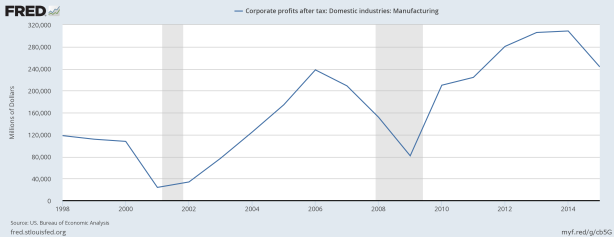

And, of course, employers have made that situation work for themselves, especially in recent years. Since the crash, corporate profits in manufacturing have rebounded spectacularly.

As long as workers have no say in how production is organized—including the technologies that are used and the surplus that is created—we can expect both manufacturing production and profits to increase while leaving workers and their jobs behind.

No matter who the president is.