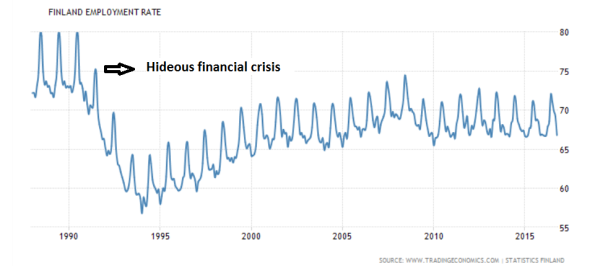

The employment rate in Finland: from a high level equilibrium to a low level equilibrium Is it possible for an economy to suddenly switch from a rather stable situation of high employment and prosperity to another rather stable situation of low unemployment which, surely in the longer run, puts the prosperity or large groups of people into jeopardy? Neoclassical economists say; ‘NO’! Lasting high unemployment is caused by real wages which are too high, which lures too many people into the labor force! (I’m not making this up – they want to cure unemployment by kicking people out of the labor market!). ‘Yes’ says Roger Farmer and say Marco Fioramanti and Robert Waldmann. The yes men seem right. When we look at for instance Finland, we see that the hideous financial crisis of 1991 led to permanently lower rate of employment, partly because unemployment became structurally higher and partly because people dropped out of the labor force altogether. How do neoclassical economists cope with such events? They use the idea of ‘natural unemployment’. ‘Natural Unemployment’ is the level of unemployment which is needed to let the economy run smoothly – we really should not aim at lowering it! As this idea is operationalized by neoclassical economists, for instance those making estimates for the European Commission (EC), it is a kind of running average of the real rate of unemployment.

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

The employment rate in Finland: from a high level equilibrium to a low level equilibrium

Is it possible for an economy to suddenly switch from a rather stable situation of high employment and prosperity to another rather stable situation of low unemployment which, surely in the longer run, puts the prosperity or large groups of people into jeopardy? Neoclassical economists say; ‘NO’! Lasting high unemployment is caused by real wages which are too high, which lures too many people into the labor force! (I’m not making this up – they want to cure unemployment by kicking people out of the labor market!). ‘Yes’ says Roger Farmer and say Marco Fioramanti and Robert Waldmann. The yes men seem right. When we look at for instance Finland, we see that the hideous financial crisis of 1991 led to permanently lower rate of employment, partly because unemployment became structurally higher and partly because people dropped out of the labor force altogether.

Is it possible for an economy to suddenly switch from a rather stable situation of high employment and prosperity to another rather stable situation of low unemployment which, surely in the longer run, puts the prosperity or large groups of people into jeopardy? Neoclassical economists say; ‘NO’! Lasting high unemployment is caused by real wages which are too high, which lures too many people into the labor force! (I’m not making this up – they want to cure unemployment by kicking people out of the labor market!). ‘Yes’ says Roger Farmer and say Marco Fioramanti and Robert Waldmann. The yes men seem right. When we look at for instance Finland, we see that the hideous financial crisis of 1991 led to permanently lower rate of employment, partly because unemployment became structurally higher and partly because people dropped out of the labor force altogether.

How do neoclassical economists cope with such events? They use the idea of ‘natural unemployment’. ‘Natural Unemployment’ is the level of unemployment which is needed to let the economy run smoothly – we really should not aim at lowering it! As this idea is operationalized by neoclassical economists, for instance those making estimates for the European Commission (EC), it is a kind of running average of the real rate of unemployment. Which means that they estimated rates of over 20% for Spain. Farmer, Fioramanti and Waldmann take issue with the idea of the ‘natural rate of unemployment’. According to Farmer, the whole concept is bogus. According to Fioramanti and Waldmann slightly different specifications of the method to estimate the rate would lead to quite different, and much lower, outcomes. Which leads to the question: why does the EC sell out to such crooked estimates? Why does it need this nonsense? Are bad economic estimates and even worse ideas used to discipline entire countries? Fioramanti and Waldmann answer this in the affirmative. Brexit has some logic to it (unlike the politicians promoting it, by the way). See also an article by Philipp Heimberger and Jakob Kapeller and Bernhard Schutz who proof the obvious (well, not all that obvious to neoclassical economists…) and show that ‘natural unemployment’ (they call it NAIRU) as estimated by the EC does not measure any kind of structural, unavoidable unemployment but cyclical unemployment. Which leads us to a topsy turvy interpretation of these estimates. While the EC understands them as the part of unavoidable unemployment and therewith not part of the output gap (the difference between the potential of an economy and its actual level) it seems more akin to the truth to understand them as estimates of this very output gap!