This thread on Twitter has attracted a lot of attention. It goes some way towards explaining why older people are generally in favour of Brexit, and why Theresa May's "strong and stable" mantra particularly appeals to the baby boomer generation. For those who aren't on Twitter, I've paraphrased part of the thread here. I have been thinking about the "strong and stable" mantra, in the context of my mum, who thinks Theresa May is great. Mum is a product of post war Social democracy (born 1947). She got 6 good O levels despite failing the 11+, and went into the civil service. She got into a mess due to creating me with my irresponsible dad, but then met my stepfather, whom she is still with. In material terms, since the early 80s my mum and my stepfather have had no money worries.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: benefits, housing, pensions

This could be interesting, too:

Nick Falvo writes Subsidized housing for francophone seniors in minority situations

NewDealdemocrat writes Declining Housing Construction

Nick Falvo writes Homelessness among older persons

Bill Haskell writes Q3 Update: Housing Delinquencies, Foreclosures and REO

This thread on Twitter has attracted a lot of attention. It goes some way towards explaining why older people are generally in favour of Brexit, and why Theresa May's "strong and stable" mantra particularly appeals to the baby boomer generation. For those who aren't on Twitter, I've paraphrased part of the thread here.

I have been thinking about the "strong and stable" mantra, in the context of my mum, who thinks Theresa May is great. Mum is a product of post war Social democracy (born 1947). She got 6 good O levels despite failing the 11+, and went into the civil service. She got into a mess due to creating me with my irresponsible dad, but then met my stepfather, whom she is still with.

In material terms, since the early 80s my mum and my stepfather have had no money worries. They've had stability from their 40s to their 70s. And they also had stability in their earlier lives through full employment, the NHS, workplace/union rights, public sector employment, education. Although they were children in the first Austerity era (late 40s/early 50s), it was their parents who'd born the brunt of that. They had the stability of post-war social democracy. Then, from 1979 onwards, they got the income from the shares. They got the wealth from property price rises. They got the dividends of Thatcherism, and they also got the pensions from post-war social democracy.

So they've had a lot of stability. Stability was their era. If you appeal to them with "Stability" they recognise themselves. And because they did well out of the upswing of Thatcherism after the rockiness of the inflation years and the disruption and "discontent" of 1978-9, they also identify with "strong". They voted for Thatcher, and she put a stop to disruption and discontent.

To them, stability came under Thatcher because she was strong, and they see May, their contemporary, reflecting it back at them. They see "strong and stable" as values they associate with their own characters. They don't see themselves as being stable because of post-war social democracy. They don't see healthcare, education, housing, rights. They see themselves as having the right qualities, the right approach to life. Their stability comes from "working hard and saving", even though they've had more holidays than anyone I've ever met and were well into the bank of his mum and dad (civil service pension). And also, as gleeful Brexiteers, they don't see any of the stability or material comfort as having come from 45 years of EEC/EU membership.

May's mantra of "Strong and Stable" resonates and reinforces how they see themselves. So they say things like, "I'm sure we'll get a good deal because Theresa May is strong" and "we can trade with Australia". Mum thinks Theresa May is "really good because I think she'll get us a good deal". This is just faith. Faith that being 'strong' works: faith that being 'strong' will restore Britain to what it was when they did well out of it. Being Strong will make you Stable.

It's delusional nonsense. It's the politics of Affect. But it's a structure of feeling. It ignores history, it locks on to characteristics. Also, of course, it's difficult to counter it by giving your parents a little lecture on the Post War settlement and the neoliberal rupture.

They see the struggles, failures & penury of their children as failures of New Labour. Borrowing money, switching jobs. They had stability because they were strong. We have instability because we are weak. We are flighty, we get into debt, we can't keep a job. Weak.

I say to them, what about my child? What about my 13 year old? She won't have what you had. Is that "strong and stable", Mum? Your granddaughter having to pay private health insurance when she might not even be able to get a job?

I see their "strong and stable", and I raise them "you have voted to make your grandchildren's lives unstable and precarious". I want to make them feel guilty for what they have done.

But when I talk to my mum and I say "you know your grandchildren almost certainly won't get a state pension" she says "I know".

They don't care.I've highlighted the comment that particularly attracted my attention. For to my mind, this is where the author's perception failed him (or her). You can't make people feel guilty about something they don't think is anything to do with them. And the baby boomer generation don't see their wealth and their entitlements as in any way connected with the materially poorer future faced by their children and their grandchildren.

Believe me, I have tried. I have spent endless hours explaining that NI contributions are not payments into a savings pot to be drawn on in retirement. I have spent almost as many hours trying to get across to older homeowners that the current value of their property has nothing to do with their hard work and everything to do with the insane rise in property prices since the 1960s. I have shown how the NI fund faces bankruptcy by 2020 unless either the state pension age rises significantly - for current generations, not just for the young - or NI contributions rise astronomically. I have patiently explained to those living on the income from savings that raising interest rates beyond what the economy can afford will make everyone, including them, poorer in the future. I have pointed out that the returns of the 1980s were anomalous and will never return. And I have commented that retaining the triple lock on state pensions, thus continually raising pensions above both earnings and inflation, will progressively immiserate the children and the unborn of today.

All my attempts failed. They did not want to know. When I said that today's pensions are paid by today's workers, and that tomorrow's pensions will be paid by tomorrow's workers (the children and unborn of today), I was shouted down. "WE PAID IN: YOU PAY OUT", they shrieked. Even those who did understand that current contributions pay current pensions, and that the wealth of the old is mirrored by the debt of the young, refused to accept any responsibility for the uncertain future faced by the young. They think they are entitled to their property wealth, their pensions and their benefits, and they are damned if they are going to relinquish any of them without a fight.

It's not that they don't care about the young. They do. After all, they have children and grandchildren. So they want their state pensions so that they can provide free childcare for their grandchildren, thus enabling their daughters to go out to work. They want the state to pay for their social care so that they can pass their property and pension wealth on to their children. They even want the triple lock to continue so that their children and grandchildren will in due course have higher state pensions.

They seem unable to see that the money they want to drain from the state to subsidise their own children must come from taxing other people's children, many of whom will be materially poorer than theirs. Or if they do see, they don't care. They don't see the cost of their demands as any of their concern. They have worked hard and paid in all their lives. Now it is time for them to reap their just rewards.

The real problem is that they do not understand the "social contract", on which our welfare system is based - and which forms the foundation of our entire social economy. The "baby boomers" have been systematically led to believe that their security in old age comes from their own efforts, not from ensuring that future generations have a bright future. That is the legacy of the "cult of the individual" which was the moral underpinning of Thatcher's revolution. The baby boomer generation bought former council houses, participated in the sell-off of state assets, contributed to defined benefit pensions, paid tax, NI and SERPS. They believe that through their own hard work and saving, they have provided for their own old age and acquired assets to pass on to future generations. Their property, pensions and benefits are simply the capital they have built up. They are entitled to them - in full.

So the reason it is so hard to shift their sense of entitlement, even though they know that future generations will not have such generous pensions and benefits, and may never own their own homes, is that they believe they have paid. Any attempt to cut their pensions and benefits, or reduce their returns from saving, or force them to draw on their wealth to pay for care, is thus seen as robbery.

But that's not how the social contract works. This is how the Government's report on intergenerational fairness describes it:

The welfare state has long been underpinned by an implicit social contract between generations. The provision of benefits and public services to the current pensioner population is funded by the taxes of the current working-age population. In turn they expect to receive similar benefits and services when they retire, and so on.

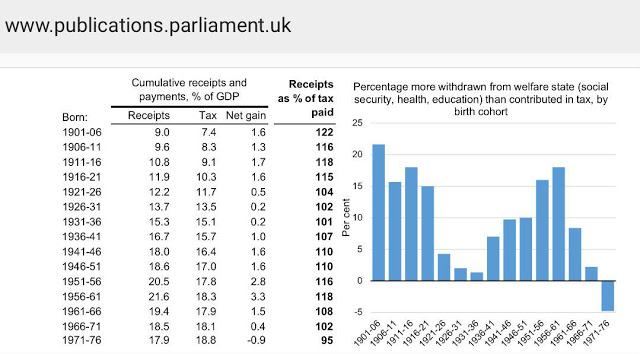

We should not be fooled by the percentages here. The oldest generation have paid in considerably less than they receive, but in money terms they both paid and received much less than those born since the war. Financially speaking, the people who have taken the most and paid the least are my own generation, those born 1956-61.

Of course, this research is out of date. The Government's report calls for further research to be undertaken, to determine what the situation is now. But it seems unlikely that the balance between tax and receipts has improved. It is more likely to have deteriorated, since people are living longer, state pensions and benefits have risen and the cost of the NHS is rocketing.

But as the Government's report explains, the contributions shortfall is not the only problem:

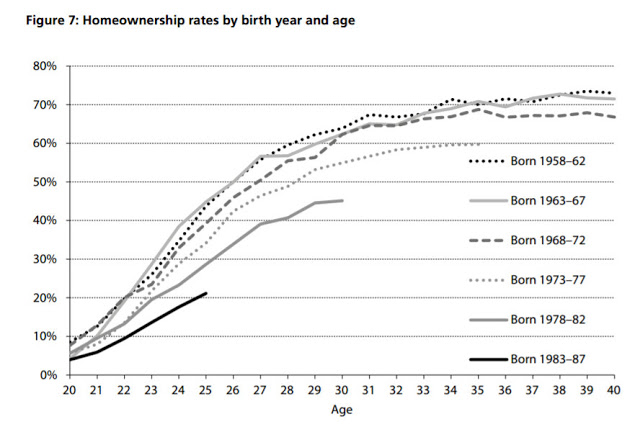

The UK economy has become skewed. Rapid and sustained rises in house prices have concentrated wealth in the hands of those who own property. Far too many young people cannot afford homeownership and instead have to pay costly private rent. Life expectancy has risen faster than anticipated at a time when the large baby boomer cohort, born between 1945 and 1965, are reaching retirement. As the taxes of working people support the retired, the ageing population places strain on those in work. Pensioners have been protected from public spending cuts that have largely been felt by younger groups. Pensioner poverty has been drastically reduced and average pensioner household incomes now exceed those of non-pensioners after housing costs. The millennial generation, born between 1981 and 2000, faces being the first in modern times to be financially worse off than its predecessors.This chart (from the same report) shows just how skewed against younger people the housing market has become:

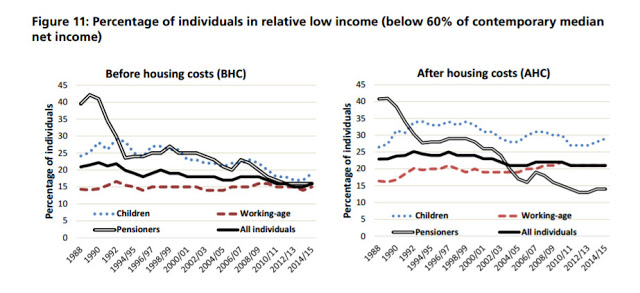

And this pair of charts shows all too clearly who, above all, bears the cost of the UK's disastrously distorted housing market:

Children do. After housing costs, 30% of children are in relative low income - compared to 15% of pensioners and 20% of working age adults. The report expresses concern about millenials, but the generation beyond looks in even worse shape.

The truth is that as long as younger generations remain "weak and flighty", highly indebted, insecure and poor, older generations' view of themselves as "strong and stable" must be a delusion. Strength and stability can only come from ensuring that future generations have prospects that are even better than those we had. By looking after themselves at the expense of future generations, older generations are undermining their own stability. And as if that were not bad enough, now they have shafted the young people on which their future depends. The economic fallout from Brexit will hurt young people far more than it will the property-owning, pension-reliant old.

The irresponsibility of older generations threatens not only the future of younger generations, but their own prosperity. Entrenching intergenerational unfairness, as the old seek to do, is folly.

Related reading:

Raising interest rates is not that simple, Lord Hague

The foolishness of the old - Pieria