From David Ruccio The effects of climate change are, as we know, distributed unequally across locations. Therefore, the damages from climate change—in terms of agriculture, crime, coastal storms, energy, human mortality, and labor—are expected to increase world inequality, by generating a large transfer of value northward and westward from poor to rich countries. What about within countries—specifically, the United States? A new report, published in Science, predicts the United States will see its levels of economic inequality increase due to the uneven geographical effects of climate change—resulting in “the largest transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in the country’s history,” according to Solomon Hsiang, the study’s lead author. What is new in the study is that, instead

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The effects of climate change are, as we know, distributed unequally across locations. Therefore, the damages from climate change—in terms of agriculture, crime, coastal storms, energy, human mortality, and labor—are expected to increase world inequality, by generating a large transfer of value northward and westward from poor to rich countries.

What about within countries—specifically, the United States?

A new report, published in Science, predicts the United States will see its levels of economic inequality increase due to the uneven geographical effects of climate change—resulting in “the largest transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in the country’s history,” according to Solomon Hsiang, the study’s lead author.

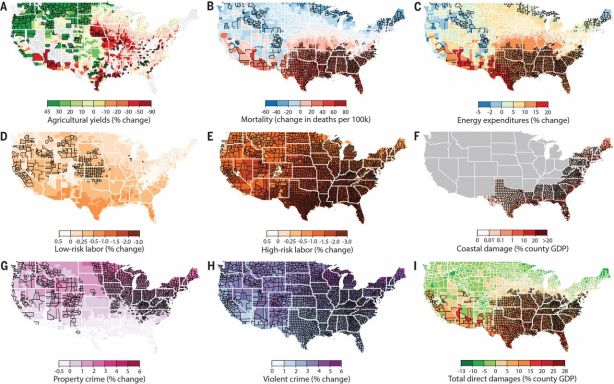

What is new in the study is that, instead of following the usual climate-change modeling approaches (which describe average impacts for large regions or the entire globe), the authors examine sub-regional, county-level effects.

The results are downright scary:

In general (except for crime and some coastal damages), Southern and Midwestern populations suffer the largest losses, while Northern and Western populations have smaller or even negative damages, the latter amounting to net gains from projected climate changes.

Combining impacts across sectors reveals that warming causes a net transfer of value from Southern, Central, and Mid-Atlantic regions toward the Pacific Northwest, the Great Lakes region, and New England. In some counties, median losses exceed 20% of gross county product (GCP), while median gains sometimes exceed 10% of GCP. Because losses are largest in regions that are already poorer on average, climate change tends to increase preexisting inequality in the United States. Nationally averaged effects, used in previous assessments, do not capture this subnational restructuring of the U.S. economy.

For example, counties in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida will be plagued by rising sea levels and more intense hurricanes, while the South and the Midwest will be threatened by increasingly rising temperatures—a trend the researchers warn can slow productivity, increase violent crime, disturb agricultural patterns, and increase energy demands and costs.

Of course, we’re still referring to regions here—not to classes. Some of the counties are poorer, others richer but there is also a great deal of inequality within them. What we’d want to know, then, is what happens to the income and wealth—as well as health, habitat, and much else—of rich and poor classes in the United States.

We don’t have that kind of information or analysis yet.

What we do know is, not everyone is going to be affected in the same way by climate change. Not across countries and certainly not within countries. That’s the problem with averages—with respect to national income, health, or climate change: they obscure or hide the different class effects of large economic and social phenomena.

What we need to remember is, global temperatures are rising as a result of the existing set of economic and social institutions. And, unless they’re changed, those same institutions are going to serve to distribute the damages caused by climate change unequally between regions and classes.

Clearly, it is time to reimagine and radically transform the way the economy is currently organized. And there’s no place better to begin that project than in the United States, where inequality is obscene and social progress has flatlined.