From David Ruccio We’ve all heard it at one time or another. Why is the price of gasoline so high? Mainstream economists respond, “it’s the market.” Or if you think you deserve a pay raise, the answer again is, “go get another offer and we’ll see if you’re worth it according to ‘the market’.” And then there’s CEO pay, which last year was 271 times the average pay of workers. Ah, it’s what “the market” has determined the appropriate compensation to be. “The market” explains everything—and, of course nothing. Chris Dillow argues that invoking “the market” (e.g., to explain the gender disparities in pay for BBC broadcasters) serves to hide from view the role of power. Talk of the “market” is therefore what Georg Lukacs called reification – the process whereby “a relation between people

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

We’ve all heard it at one time or another.

Why is the price of gasoline so high? Mainstream economists respond, “it’s the market.” Or if you think you deserve a pay raise, the answer again is, “go get another offer and we’ll see if you’re worth it according to ‘the market’.”

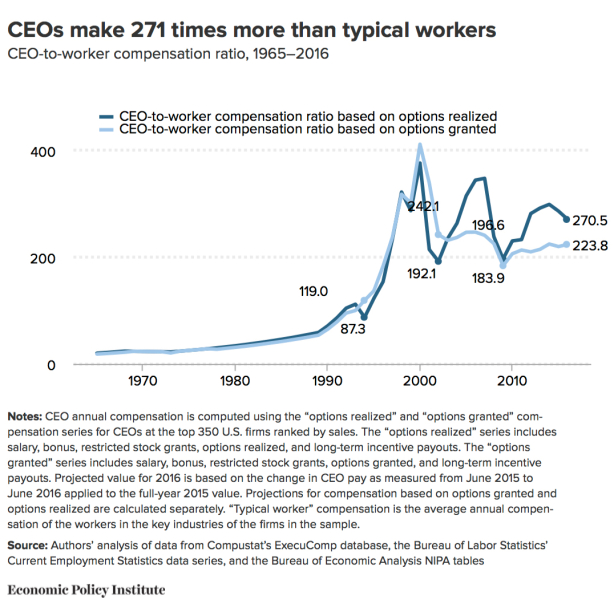

And then there’s CEO pay, which last year was 271 times the average pay of workers. Ah, it’s what “the market” has determined the appropriate compensation to be.

“The market” explains everything—and, of course nothing.

Chris Dillow argues that invoking “the market” (e.g., to explain the gender disparities in pay for BBC broadcasters) serves to hide from view the role of power.

Talk of the “market” is therefore what Georg Lukacs called reification – the process whereby “a relation between people takes on the character of a thing and thus acquires a ‘phantom objectivity.’” It obfuscates the fact that wages are set by the power of one person over another. Such obfuscation serves a profoundly ideological function; it effaces the fact that the capitalist economy is based upon power relationships.

Not even neoclassical economists stop with references to the “the market.” That’s just the first step of the explanation. The next step is to analyze “the market” in terms of its ultimate—given or exogenous—factors determining supply and demand. Their story is that “the market” can finally be reduced to and explained by preferences, resource endowments, and technology. In other words, according to neoclassical economists, market prices—whether for gasoline, workers’ pay, and CEO compensation—reflect consumer preferences, households’ endowments, and human know-how, all of which are considered to be prior to and independent of the economy.

That’s the way formal neoclassical economics works. But mainstream economists are also content to let the myth of “the market” persist in the minds of their students and the proverbial person in the street because it protects markets from what they consider to be unwarranted regulation and intervention. “The market” is turned into an abstract entity that merely reflects human nature. And if anyone wants to change the results—to change, for example, the price of gasoline, workers’ wages, or CEO compensation—they face the daunting task of changing human nature.

But there’s another side to the myth of “the market.” It becomes symbolic of an entire system gone awry—and which therefore can be criticized and replaced.

Instead of “the market,” we might refer to individual markets—not just to markets for gasoline, workers’ ability to labor, or CEOs’ skills but to markets for different kinds of gasoline, different groups of workers, or CEOs in different industries. Or, alternatively, we might invoke the different roles producers, consumers, workers, corporate executives, government officials, and so on play in determining market outcomes. All of those individual markets and market participants might then be regulated to produce different outcomes.

But if it’s “the market” that is to blame, then it’s the entire system—not one or another market or market participant—that needs to be radically transformed.

If mainstream economists defend and celebrate “the market,” critics of market outcomes—of which there are many—can then move to a more systemic assessment, to become critics of the economy as a whole.

And once that happens, critics can then imagine and begin to create a different economic system, one that is not governed by “the market.” Such an alternative system might have markets, lots of different kinds of markets. But it would have a different logic, a different way of operating, with very different outcomes.

Such an alternative economy exists on the other side, beyond the myth of “the market.”