From David Ruccio Thanks to the release of the so-called Paradise Papers, and the additional research conducted by Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Tørsløv, and Ludvig Wier, we know that a large share of the surplus captured by corporations is artificially shifted to tax havens all over the world. This, of course, is on top of the conspicuous tax evasion practiced by the individual holders of a large portion of the world’s wealth. Thus, for example, U.S. multinational corporations now claim to generate 63 percent of all their foreign profits in six tax havens, the most prominent being the Netherlands, Bermuda and the Caribbean, and Ireland. This is 20 points more than in 2006.* What this means is that, in the tax havens themselves, low tax rates can generate large tax revenues relative to the

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Thanks to the release of the so-called Paradise Papers, and the additional research conducted by Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Tørsløv, and Ludvig Wier, we know that a large share of the surplus captured by corporations is artificially shifted to tax havens all over the world. This, of course, is on top of the conspicuous tax evasion practiced by the individual holders of a large portion of the world’s wealth.

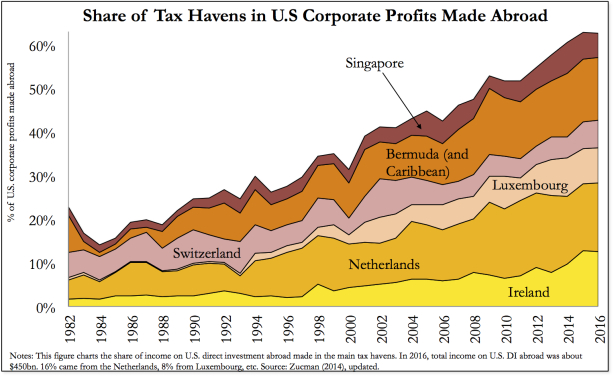

Thus, for example, U.S. multinational corporations now claim to generate 63 percent of all their foreign profits in six tax havens, the most prominent being the Netherlands, Bermuda and the Caribbean, and Ireland. This is 20 points more than in 2006.*

What this means is that, in the tax havens themselves, low tax rates can generate large tax revenues relative to the size of the economies. But it also means large multinational corporations can play off one tax have against others, and shift their profits to those with the most generous laws and regulations—as Apple has recently done, by relocating tens of billions of dollars from Ireland to the small island of Jersey (which typically does not tax corporate income and is largely exempt from European Union tax regulations).

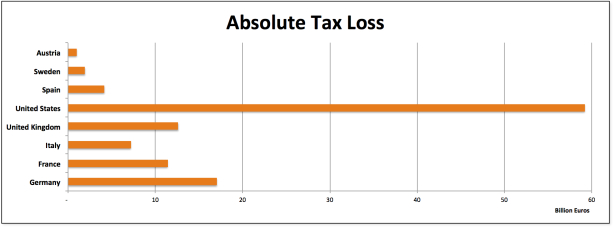

It also means that the putative home countries of the multinational corporations lose potential tax revenues, which means a larger tax burden is imposed on others, especially individuals and small businesses.

In the case of the United States, Zucman and his colleagues estimate that the United States loses almost 60 billion euros to tax havens (about three quarters from European Union tax havens and the rest from tax havens elsewhere), which amounts to about 25 percent of the corporate tax revenue it currently collects.

As Zucman explains,

Tax havens are a key driver of global inequality, because the main beneficiaries are the shareholders of the companies that use them to dodge taxes.

Clearly, the existing rules are such that large multinational corporations win twice: first, by capturing more and more surplus from their workers, whose wages have barely budged in recent decades; and second, by using tax havens to avoid paying taxes on a large portion of that surplus, thus shifting the tax burden onto workers at home.

*I created the charts in this post based on data that have been made publicly available by Zucman, Tørsløv, and Wier.