I came to think about this dictum when reading Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Tenty-First Century. Piketty refuses to use the term ‘human capital’ in his inequality analysis. I think there are many good reasons not to include ‘human capital’ in economic analyses. Let me just give one — perhaps analytically the most important one — reason and elaborate a little on that. In modern endogenous growth theory knowledge (ideas) is presented as the locomotive of growth. But as Allyn Young, Piero Sraffa and others had shown already in the 1920s, knowledge is also something that has to do with increasing returns to scale and therefore not really compatible with neoclassical economics with its emphasis on constant returns to scale. Increasing returns generated by non-rivalry between ideas is simply not compatible with pure competition and the simplistic invisible hand dogma. That is probably also the reason why neoclassical economists have been so reluctant to embrace the theory wholeheartedly. Neoclassical economics has tried to save itself by blurring the distinction between ‘human capital’ and knowledge/ideas. But knowledge or ideas should not be confused with ‘human capital.’ Chad Jones gives a succinct and accessible account of the difference: Of the three statevariables that we endogenize, ideas have been the hardest to bring into the applied general equilibrium structure.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

I came to think about this dictum when reading Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Tenty-First Century.

Piketty refuses to use the term ‘human capital’ in his inequality analysis.

I think there are many good reasons not to include ‘human capital’ in economic analyses. Let me just give one — perhaps analytically the most important one — reason and elaborate a little on that.

In modern endogenous growth theory knowledge (ideas) is presented as the locomotive of growth. But as Allyn Young, Piero Sraffa and others had shown already in the 1920s, knowledge is also something that has to do with increasing returns to scale and therefore not really compatible with neoclassical economics with its emphasis on constant returns to scale.

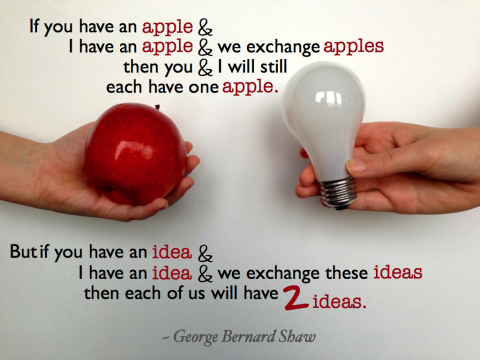

Increasing returns generated by non-rivalry between ideas is simply not compatible with pure competition and the simplistic invisible hand dogma. That is probably also the reason why neoclassical economists have been so reluctant to embrace the theory wholeheartedly.

Neoclassical economics has tried to save itself by blurring the distinction between ‘human capital’ and knowledge/ideas. But knowledge or ideas should not be confused with ‘human capital.’ Chad Jones gives a succinct and accessible account of the difference:

Of the three statevariables that we endogenize, ideas have been the hardest to bring into the applied general equilibrium structure. The difficulty arises because of the defining characteristic of an idea, that it is a pure nonrival good. A given idea is not scarce in the same way that land or capital or other objects are scarce; instead, an idea can be used by any number of people simultaneously without congestion or depletion.

Because they are nonrival goods, ideas force two distinct changes in our thinking about growth, changes that are sometimes conflated but are logically distinct. Ideas introduce scale effects. They also change the feasible and optimal economic institutions. The institutional implications have attracted more attention but the scale effects are more important for understanding the big sweep of human history.

The distinction between rival and nonrival goods is easy to blur at the aggregate level but inescapable in any microeconomic setting. Picture, for example, a house that is under construction. The land on which it sits, capital in the form of a measuring tape, and the human capital of the carpenter are all rival goods. They can be used to build this house but not simultaneously any other. Contrast this with the Pythagorean Theorem, which the carpenter uses implicitly by constructing a triangle with sides in the proportions of 3, 4 and 5. This idea is nonrival. Every carpenter in the world can use it at the same time to create a right angle …

Ideas and human capital are fundamentally distinct. At the micro level, human capital in our triangle example literally consists of new connections between neurons in a carpenter’s head, a rival good. The 3-4-5 triangle is the nonrival idea. At the macro level, one cannot state the assertion that skill-biased technical change is increasing the demand for education without distinguishing between ideas and human capital.

In one way one might say that increasing returns is the darkness of the mainstream economics heart. And this is something most mainstream economists don’t really want to talk about. They prefer to look the other way and pretend that increasing returns are possible to seamlessly incorporate into the received paradigm — and talking about ‘human capital’ rather than knowledge/ideas makes this more easily digested.