From Dean Baker It is striking how the media universally accept the idea that patent and copyright monopolies are somehow free trade. We get that the people who own and control major news outlets like these forms of protection, but it is incredibly dishonest to claim that they are somehow free trade. We get this story yet again in a NYT piece complaining about China’s “theft” of intellectual property, while telling readers about how Trump’s proposed tariffs show his: “resolve to turn away from a decades-long move toward open markets and integrated world economies and toward a more starkly protectionist approach that erects barriers around a Fortress America.” While we are supposed to be alarmed about tariffs of 10 percent and 25 percent on steel and aluminum, patents and copyrights are

Topics:

Dean Baker considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Dean Baker

It is striking how the media universally accept the idea that patent and copyright monopolies are somehow free trade. We get that the people who own and control major news outlets like these forms of protection, but it is incredibly dishonest to claim that they are somehow free trade.

We get this story yet again in a NYT piece complaining about China’s “theft” of intellectual property, while telling readers about how Trump’s proposed tariffs show his:

“resolve to turn away from a decades-long move toward open markets and integrated world economies and toward a more starkly protectionist approach that erects barriers around a Fortress America.”

While we are supposed to be alarmed about tariffs of 10 percent and 25 percent on steel and aluminum, patents and copyrights are effectively tariffs of many thousand percent, often raising the price of protected items tenfold or even a hundredfold. The economic impact of increased protectionism of this type has been enormous.

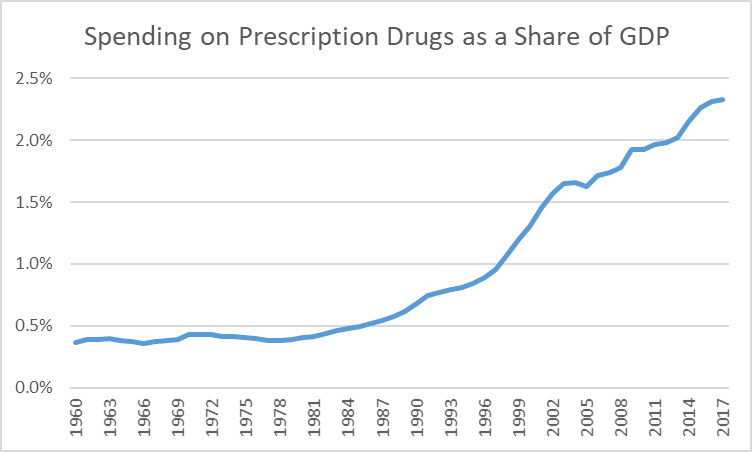

This can be seen clearly in the case of prescription drugs, where spending went from around 0.4 percent of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s to 2.4 percent of GDP ($450 billion) in 2017, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Since drugs are almost invariably cheap to manufacture, we would likely be spending less than $80 billion a year in the absence of patent and related protections, implying a cost of protectionism of more than $370 billion, and this is just from drug patents. Adding in costs in medical equipment, software, and other areas would likely more than double and quite possibly triple this amount.

The supporters of this protectionism argue that we need patent and copyright monopolies to provide an incentive for innovation and creative work. However there are two major flaws in this argument.

First, while these monopolies are one way to finance research, they are not the only way. There are other mechanisms, such as direct government funding (we already spend more than $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health). Given the enormous cost associated with this protectionism it would be reasonable to be debating the relative merits of alternatives. (See also chapter 5 of Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

The other point is even simpler. We have been making patent and copyright protection stronger and longer for the last four decades. We know that this shifts more money from the rest of us to those who benefit from these protections. Even if we decide that these mechanisms are the best way to finance innovation and creative work, it does not mean that making them stronger and longer is always justified.

We should be asking the question of how much additional innovation or creative work do we get for an increment to strength and length. This debate never takes place.

This creates the absurd situation where we put in place policies that are designed to transfer money from the rest of us to people like Bill Gates and then we wonder why we have so much income inequality. And the best part of the story is that some of the big gainers from these protections will even finance research as to why we have so much inequality, as long as it doesn’t ask questions about patent and copyright protection.