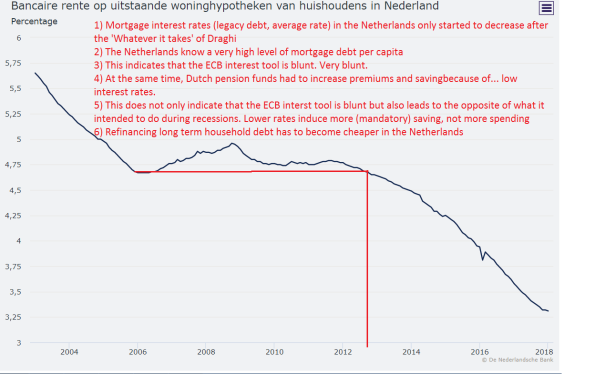

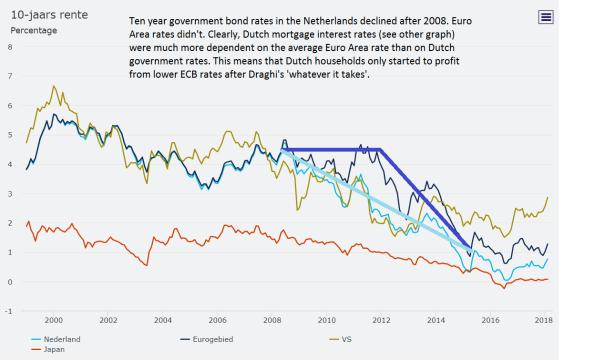

Only after Mario Draghi’s ‘Whatever it takes’ (26 July 2012) low ECB policy interest rates started to translate decisively to lower rates for Mediterranean Eurozone borrowers. But ‘WIT’ did not only save (or at least: made live a little easier for) Italian and Spanish borrowers with legacy debts. Somehow, Dutch mortgage rates were also tied to the European bond rate instead of the ECB rate oor Dutch government bond rates (second graph) which meant that it was only after 26 July 2012, four years after the onset of the crisis, that Dutch households too could start with decreasing the amount of ‘debt service’ they had to pay (interest on savings accounts is of course also lower – but those rates did start to decline before 26 July 2012). What does this mean for economic theory? According

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Only after Mario Draghi’s ‘Whatever it takes’ (26 July 2012) low ECB policy interest rates started to translate decisively to lower rates for Mediterranean Eurozone borrowers. But ‘WIT’ did not only save (or at least: made live a little easier for) Italian and Spanish borrowers with legacy debts. Somehow, Dutch mortgage rates were also tied to the European bond rate instead of the ECB rate oor Dutch government bond rates (second graph) which meant that it was only after 26 July 2012, four years after the onset of the crisis, that Dutch households too could start with decreasing the amount of ‘debt service’ they had to pay (interest on savings accounts is of course also lower – but those rates did start to decline before 26 July 2012).

Only after Mario Draghi’s ‘Whatever it takes’ (26 July 2012) low ECB policy interest rates started to translate decisively to lower rates for Mediterranean Eurozone borrowers. But ‘WIT’ did not only save (or at least: made live a little easier for) Italian and Spanish borrowers with legacy debts. Somehow, Dutch mortgage rates were also tied to the European bond rate instead of the ECB rate oor Dutch government bond rates (second graph) which meant that it was only after 26 July 2012, four years after the onset of the crisis, that Dutch households too could start with decreasing the amount of ‘debt service’ they had to pay (interest on savings accounts is of course also lower – but those rates did start to decline before 26 July 2012).

What does this mean for economic theory? According to mainstream economists there is a ‘natural rate of interest’ which is consistent with the general equilibrium ‘bliss point’. Considering the amount of labour and capital, the state of the productive arts and the preferences of the representative consumer, this is the rate which makes consumption and employment and investment are just ‘right’. Ideas like these are the theoretical foundation of interest rate policies of institutions like the Fed and the ECB. In case of the ECB, one can pose the question if, even when one accepts the idea of the natural rate of interest, an area as politically diverse als the Euro Area has one rate of natural interest or multiple rates. One can also yield a more institutional criticism: there is one central bank rate of interest. But there are multiple countries with a multitude of banks and sectors which leads to a plethora of lending rates which means that the central bank rate will be translated in real world rates in a plethora of ways. How does a low central bank interest rate translate to national rates of, for instance, households borrowing from Credit Agricole in France, companies borrowing from Deutsche Bank in Germany (aside – how do you spell ‘Zombie’ in German?) or students borrowing from the government in the Netherlands? It seems that – I do not know the details – in the case of Dutch mortgages the mortgage risk models of Dutch banks were tied to the average Euro Area bond rate and not to either the Dutch government bond rate or the ECB rate. Details matter! Aside of this, in the Netherlands low ECB policy rates translate into lower calculated ‘risk free’ rates for pension funds which, in the Dutch case, means that pension funds by law have to increase premiums. Which means that contrary to the assumptions of the mainstream model, lower rates do not lead to less saving and more spending but to more (pension)saving and less spending. A last point: lower mortgage rates are good for households with legacy debt. But in the medium run they also tend to jack up house prices, which we do not want and which is another aspect of the real world which is not typically assessed in the models… All things considered, we might better call the natural rate the ‘unreal’ rate’.

Aside – whatever you think of the unreal rate, as long as a central bank has a role to play in cyclical policies especially a Euro Area central bank has to be able to do ‘whatever it takes’ as there is no room for Euro Area fiscal policies.